The Australian punk scene, as far as the UK was concerned during the late 70s, amounted to The Birthday Party and The Saints. Both bands relocated to London, which no doubt helped with the column inches, while their fellow countrymen remained invisible. There were isolated events such as Radio Birdman playing a handful of gigs in and around the capital shortly before they split up, plus some excitement surrounding The Victims’ debut single, ‘Television Addict’, but these were fleeting moments. And yet still they add up to more exposure than Australia’s post-punk scene could muster. Despite pockets of activity across the country, outside interest was even smaller. Melbourne’s Little Bands, for example, only caused a stir within their own circle, although they did have the good fortune to count an aspiring filmmaker among their number.

Richard Lowenstein was a student at the Swinburne Institute of Technology as the Little Bands began to emerge, toiling away in the Film and Television Department. For his graduation film he turned to a book written by his mother, the historian and activist Wendy Lowenstein, Weevils In The Flour. This was an oral history of Australia during the Great Depression and translated itself into a remarkably assured 25-minute dramatized documentary by the name of Evictions. It picked up the award for Best Short at the Melbourne International Film Festival and would lead to Lowenstein’s 1984 feature debut, Strikebound, which again drew inspiration from one of his mother’s books. This time around the focus was on Dead Men Don’t Dig Coal and a 1930s coal miners’ strike which, in conjunction with Evictions, suggested a career as a politically-minded filmmaker. But take a closer look and other concerns begin to reveal themselves.

One of Lowenstein’s classmates at the Swinburne Institute was Tim McLaughlan. The pair worked on a number of student films together, including Evictions for which McLaughlan provided the score. Despite the subject matter his compositions were minimal and sparingly used synth pieces which pointed towards his presence in The Ears, an art-punk outfit who also happened to share a house with Lowenstein in Melbourne’s Richmond area. Though short-lived – formed in 1979, finished by 1981 – they nevertheless managed a couple of singles (including one of the Missing Link label, home to The Birthday Party) and convinced their housemate to ‘borrow’ some equipment from the film department in order to shoot a promo. ‘Leap for Lunch’ became his first music video, kick-starting a key development in the young filmmaker’s career.

Throughout the eighties Lowenstein teamed up with most of Australia and New Zealand’s major musical talent. He would become INXS’ director of choice and he also provided promos for the likes of Tim Finn, The Church, Crowded House, Hunters & Collectors and Models. When U2 wanted a brief concert film to commemorate a 19-date tour of the country, it was Lowenstein who was called upon (the videos for ‘Desire’ and ‘Angel Of Harlem’ were also his responsibility). Similarly when the ‘Australian Made’ string of concerts – which brought together eight homegrown acts ranging from INXS and The Saints to Divinyls and Mental as Anything – needed a feature-length documentary, there was just the one obvious choice. Oddly enough, Pete Townshend also approached Lowenstein when turning his 1984 solo album White City into a 60-minute slice of dour kitchen sink realism.

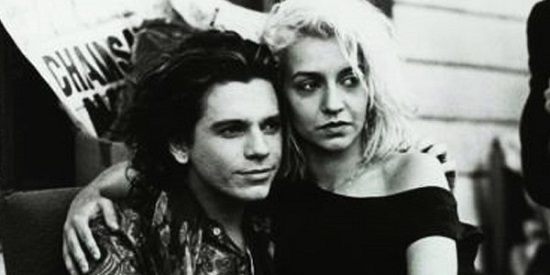

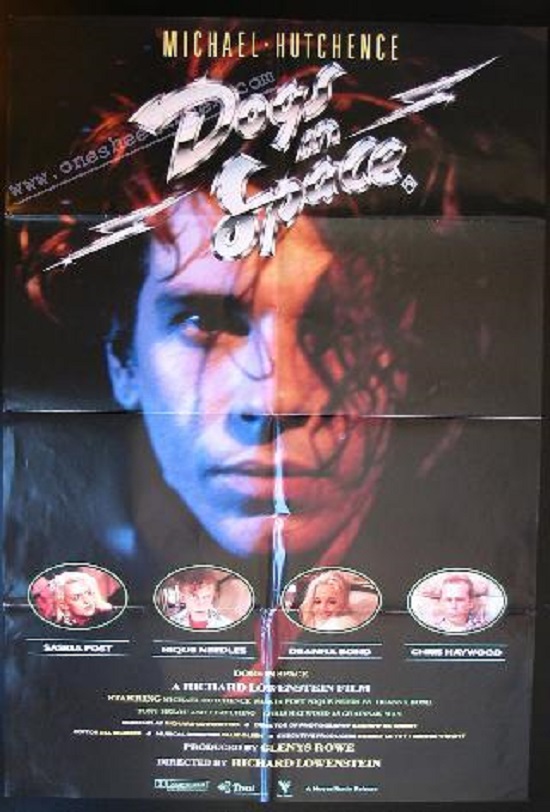

Within this wider context the decision to follow-up the 1930s coal mine setting of Strikebound with a recreation of Melbourne’s recent post-punk past makes perfect sense. Dogs in Space would not only take its title from a song by The Ears, it would also (loosely) re-tell the time Lowenstein spent living with the band and serve as an overall survey of the Little Band scene. INXS frontman Michael Hutchence was brought in to embody Ears frontman Sam Sejavka (the real Sejavka cameos as a character named Michael), while others reformed their old groups for one-off appearances or played versions of themselves à la Michael Winterbottom’s 24 Hour Party People. Lowenstein, incidentally, wrote himself entirely out of the picture, though he did make use of the original house (which had also served as the location for that ‘Leap for Lunch’ promo).

The Little Band movement took its name from a night at the Champion Hotel in the Fitzroy suburb. The Boys Next Door (as The Birthday Party were first known) had needed a group to support them for a single gig and so some friends of noise outfit Primitive Calculators borrowed the band’s equipment to form an impromptu one-night-only act. At the time the Primitive Calculators were neighbours to the synth-based Whirlywirld and together they hit upon the idea of sharing their guitars and drum machines with temporary bands and the occasional side project. The rules differ depending on who is being interviewed, but they are generally laid out as follows: each group would play for no longer than 15 minutes and at no more than two gigs. Among those to be invented at the Champion were Thrush and the Cunts, Too Fat to Fit through the Door, The Lunatic Fringe and The Shower Scene from Psycho. Some defied the rules and went on to play genuine gigs and some used the nights as an early testing ground. Marie Hoy was a regular presence, as were a pre-Dead Can Dance Lisa Gerrard and Brendan Perry.

The key influences are laid out in Dogs in Space‘s pre-credits sequence. A quote from Iggy Pop opens proceedings, as does a track from his Soldier LP. The scene is a queue for a David Bowie concert, a queue that famously lasted for the best part of a month – almost three weeks for the tickets themselves and then another week for the actual gig – earning itself coverage in the Australian media and a place in local legend. Lowenstein wasn’t able to attend owing to film school priorities, though many of his future housemates did; clearly catching Bowie on the ‘Isolar II’ tour (post-“Heroes”, pre-Lodger) was a major deal for these kids. Brian Eno also puts in an appearance later on thanks to the opening track of Another Green World, plus the influence of The Velvet Underground, Television and the UK and US punk scenes is all over the music. Lou Reed’s infamous Sydney Airport interview from 1974 had also made an impact: “What do you spend your money on?” “Drugs.”

It was in the Bowie queue that Sejavka was first introduced to heroin. His girlfriend of the time later died of an overdose and it is to her, Christine Harding, that Dogs in Space is dedicated. As such, this isn’t perhaps the love letter to Lowenstein’s youth that it could have been. He was still only in his mid-twenties during production, and less than a decade had passed since his student days, yet an undoubtedly bittersweet taste presents itself throughout. Anyone expecting an exercise in nostalgia – an Australian Graffiti so to speak, albeit set in the late 70s rather than the early 60s – is likely to be stunned by the less-than-rosy undercurrents. Certainly, there’s a celebration of the music in Dogs in Space and fondness for student living (or, in the case of many of the Little Bands, the $50-a-week dole money that effectively served as arts grants), but not so much the excesses of the scene. Lowenstein acknowledges that these were mostly middle class kids who came from good homes (“suburban fuckwits” according to the Primitive Calculators’ Stuart Grant many years later) and were slumming it for a while, but nevertheless found themselves with serious drug habits.

Not that efforts were made to ensure as downbeat an appearance as possible. Whereas his feature debut Strikebound had been shot on low-grade 16mm stock to maintain a documentary veneer, here Lowenstein opted for 35mm, Cinemascope and utilised lengthy Steadicam takes or elaborate crane shots whenever the opportunity arose. Such choices provide a swagger and a confidence entirely appropriate for a film about a group of people who believe themselves to be bulletproof, though never to a point where it undermines the authenticity. Sejavka and McLaughlan were both employed as script consultants with Whirlywirld’s Ollie Olsen (formerly of The Young Charlatans, alongside The Birthday Party’s Rowland S. Howard) overseeing the musical side of things. He encouraged the likes of Thrush and the Cunts and Too Fat to Fit through the Door to relive former glories and peppered the soundtrack with some absolute gems: the pop-punk exuberance of ‘True Love’ by the Marching Girls and a stunningly realised scene set to Iggy Pop’s ‘The Endless Sea’.

Hutchence, of course, had no connection to the Little Bands scene. INXS were a Sydney group, born out of a schoolboy band and bearing little resemblance to The Ears’ tracks or Olsen numbers which their lead singer performs in Dogs in Space. (At the time of filming they were big in their native Oz and on the verge of an international breakthrough; new wave beginnings having given way to more straightforward MOR stylings.) Yet Hutchence acquits himself well for his acting debut and looks uncannily alike the man he’s loosely embodying. Some critics were quick to pick up on the pouty, self-conscious aspects of his performance, though friends of Sejavka attest to their authenticity. Indeed, Sejavka’s own mother once mistook Hutchence for her son when he appeared on the Aussie pop show Countdown.

But it isn’t all about Sam, either the real-life one or his fictional counterpart. Lowenstein co-opts the multi-layered dialogue approach of Robert Altman and has his Steadicam wanders from person-to-person and conversation-to-conversation. The intent of Dogs in Space is to capture the milieu and it does so admirably, taking in the people, the places, the music and the drugs. Lowenstein and Sejavka fell out immediately after its release owing to the latter’s portrayal (and his belief that the film had somehow implicated him in Harding’s death), which only goes to show how accurate the film is when it comes to certain aspects. I’m not in any way suggesting here that Sejavka was indeed guilty, but rather that the sense of reality elsewhere makes the fictional elements all the more difficult to detect. Dogs in Space is slippery like that, as loose and wayward as you would expect given the Altman influence, an almost-document of its time, and a great encapsulation of the Little Bands scene.