First there is nothing. Then a drone against a black screen. The increasingly deranged squall violently snaps into a noise akin to a jet descending at kamikaze velocity, axing your mind split open. These are the opening seconds of the new Todd Haynes documentary, and the eviscerating sound of John Cale’s isolated viola from a recording of ‘Heroin’. A quote fills the visual void: “Music fathoms the sky.”

A definitive film about The Velvet Underground might be deemed long awaited were it not for the length of time it took the actual subjects to earn a tangible level of acclaim or success. In the initial phase, including Charles Baudelaire’s satisfyingly portentous statement, Haynes draws the timeline in mind-scrambling detail, decadently framing the band, their work and the scene from which they came, one so spectacularly vibrant that its numerous combatants dominate much of the two-hour runtime.

As this documentary illustrates, The Velvet Underground existed, at least initially, on the fringes of society and the boundaries of taste but at the epicentre of the era’s avant-garde scene. So it is that, in setting the scene, the range of talking heads include the minimalist composer La Monte Young, cinematic figurehead Jonas Mekas, and, of course, Factory impresario Andy Warhol, capturing the multinational, multidisciplinary and multimedia creative scope that would, ultimately, recontextualise popular culture.

Speaking to tQ, Haynes depicts this as a once in a lifetime community, working across the visual arts, music, dance and poetry. “It was absolutely a unique, distinct and short-lived period,” he explains, outlining the ambitions that differentiate previous projects such as 1987’s experimental biopic Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, the 1998 neo-Bowie glam rush of Velvet Goldmine and dizzying Dylan hexagon in 2007’s I’m Not There. “I wanted to try to put us back in that time and place. The reason why that felt essentially something to do in a documentary is because the avant-garde cinema associated with the band is the only place The Velvet Underground was ever filmed during the years they were putting out records.”

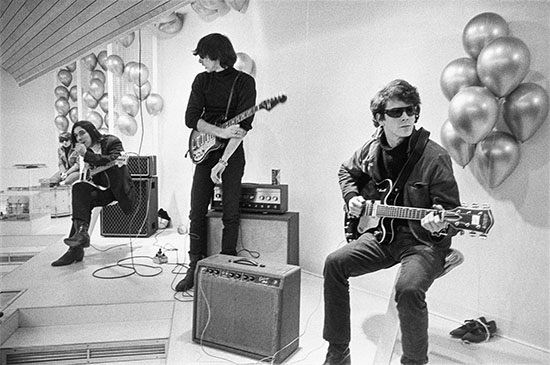

For much of his audaciously immersive film, particularly the opening passage focusing on the group’s 1964 formation and release of their debut album, The Velvet Underground & Nico, Haynes deploys split screens, mirroring the cinematic technique used by Warhol in movies such as 1966’s Chelsea Girls. The band are introduced via their Factory screen tests, providing an intimate juxtaposition to the backstories that brought Lou Reed, John Cale, Sterling Morrison and Moe Tucker together, while further amplifying the sensory attack of the documentary.

Cale, the son of a coal miner who had travelled to the USA in 1963 from Wales with a Leonard Bernstein scholarship, discusses the jarring but alchemic fusion and friction of his classically trained musical skills against the literary intent of Reed. He is presented as a sickly, sexually conflicted coiled spring – “a tortured person”, according to Warhol superstar Mary Woronov – who earned his songwriting chops knocking out production line pop songs, like so many Brillo boxes, at Pickwick Records. These included ‘The Ostrich’ which, amusingly, his sister, Merrill Reed Weiner is captured dancing to by Haynes.

“We understood how our differences, if cultivated, could turn everything in music on its head and show what startling possibilities awaited us,” Cale elaborated in a recent Uncut feature to promote the film. “There was always room for a conventionally structured song, but those methods were old hat and uninteresting to both of us. We figured that my obsession with creating dissonance AND NOISE from an orchestral perspective, combined with his lyrical bent, the future would be ours to create. It took a while for a four-piece rock band to get there…but it happened.”

The 1963 Michael Leigh paperback that gave the band their name flashes on the screen, as Haynes builds the initial narrative. According to one of countless myths, it was found on the street by filmmaker Tony Conrad, a former resident in Cale and Reed’s Ludlow Street apartment, detailing a reported rise in paraphilia. “Here is an incredible book. It will shock and amaze you. But as a documentary on the sexual corruption of our age, it is a must for every thinking adult,” reads the cover.

Thematically outré themes like this would underpin The Velvet Underground in their singular earliest incarnation. Succinctly, Cale describes their principal objectives as: “How to be elegant and how to be brutal”. With the four-piece complete, live dates followed and they were spotted playing a residency at Café Bizarre by filmmaker Barbara Rubin, prompting a visit from Warhol, then looking for a house band to front “the biggest discotheque in the world” aka the Exploding Plastic Inevitable.

Woronov recounts the “unbelievable” sight of the band arriving for an audition at the Factory and immediately launching into ‘Heroin’. A similarly confrontational story is told, coincidentally, in a second new film, The Velvet Underground Played At My High School, a recent award-winner on the global festival circuit. The animated short recreates the group’s first live concert which, improbably, took place at Summit High School in New Jersey on December 11, 1965, before a group of teenage students.

Director and NYU professor Anthony Jannelli was at the show and, speaking to tQ, explained how the gig, which was organised by the band’s former manager and rock journalist Al Aronowitz, virtually cleared the auditorium of a crowd only just beginning to comprehend bands like The Beach Boys and The Beatles. “They didn’t really know what to do with this music. There was no context for the avant-garde. There was no context for art-rock,” he says.

“The Velvet Underground knew exactly who the audience was and what they were going to be playing in front of. They weren’t going to change anything about their presentation or their song selection,” he comments, in reference to the set of ‘There She Goes Again’, ‘Venus In Furs’ and ‘Heroin’. “There’s something absolutely beautiful about that.”

To capture this period, Haynes deploys pacey edits of live footage shot at a variety of events, including their – again, totally incongruous – concert at the New York Society For Clinical Psychiatry a few months later, featuring onstage dancing from Edie Sedgwick and Warhol’s whip-wielding sidekick Gerard Malanga. The response from one onlooker, according to a review in the New York Herald Tribune, was: “I’m ready to vomit.”

Such a bewildered reaction to the band’s music was not uncommon. “The Velvet Underground is totally unimpressive,” wrote Larry Kasdan in The Michigan Daily. “Each one of their songs seems to last about three hours. The band makes a sound that can only be compared to a railroad shunting yard, metal wheels screeching to a halt on the tracks…It is only an extension to our national disease, our social insensitivity. We are a dying culture and Warhol is holding our failing hand and sketching the carcinoma in our soul.”

Undeterred, the Factory collective took the EPI, which had attracted the likes of Jackie Kennedy, Walter Cronkite and Rudolf Nureyev to the Dom in Manhattan, on the road. Their arrival in California would confirm the band’s utter displacement from the prevailing mood across mainstream society in North America and beyond. “Compared to the West Coast hippie counterculture with its communal essentialism and hypocritical utopias, the Velvets and the whole Warhol underground seemed diabolically unwholesome and dangerous and – whether actually gay or not – queer in every sense of what the word once meant,” read the accompanying production notes.

To put it another way: "They were hippies. We hated them," Woronov tells Haynes of their Los Angeles experience. The feeling was mutual, with Cher, of all people, concluding that the EPI “will replace nothing except suicide”. Such a contradiction sits at the centre of this spellbinding documentary as testament to The Velvet Underground’s eternal provocation. To this outsiderdom, Mekas, to whom the film is dedicated, declares in an interview with the director: “We are not part of the subculture or counterculture. We are the culture.”

Haynes mines a stunning, exhilarating and “intensely visual collection” of material, much of it previously unseen, and sourced from the Andy Warhol Museum in his hometown of Pittsburgh. Among the more unlikely highlights is footage of the band having their horoscopes read during downtime amongst the pop artist’s glitterati. Sadly, we don’t see them tearing through a near endless live version of ‘What Goes On’ before about six people in 1969. As Haynes confirms, virtually no such recordings exist, save for a 1966 jam in the Factory, noteworthy for many reasons, including a police officer turning down Reed’s amp.

We then see the ejection of various figures who had provided the fulcrum for the above. Nico – said by Cale to have “wandered into the situation and then quietly wandered off” – Warhol – fresh from meeting Brian Epstein in London to discuss promoting the band in Europe, according to Blake Gopnik’s recent biography – and then Cale are unexpectedly ousted, generally at Reed’s behest. The band’s second album, White Light/White Heat, recorded in an aneurysm of amphetamines (the word even judders from Reed’s mouth during ‘Sister Ray’’s noise-rock motherlode) is described by him in archival material as “the speediest album there was”.

This period blitzes past as communication, cooperation and, ultimately, friendship between the founding members disintegrates. Haynes considers their duality as “almost like a formative love relationship”. He explains: “These two remarkable people found themselves in a situation to bond and, in some ways, decide that they were going to stand together against the world for a certain amount of time and allow the concentration of their artistic ideas to foment, allow the drugs that they were taking to further isolate them and to utilise a sense of contempt for things around them to fuel their artistic mission.”

Understandably, the closing stages of the film, spanning the eponymous third album and their fourth, Loaded, lack the knockout power of what has come before. There is minimal footage of the group from this era, a reality underlined by a split screen presentation. Cale is replaced by Doug Yule, experimentation is sidelined in favour of what Jonathan Richman, a teenage fanatic of the band, observes as a “much quieter” sonic nuance and, perhaps most disturbingly, paisley shirts rather than all-black attire.

But, of course, this was a period that produced some of The Velvet Underground’s greatest – albeit radically different – songs, looser material to transcend their uptight roots. It was music that spoke of the redemptive power of rock’n’roll, despite an abject public response to this liberation. Haynes believes Reed was much happier in charge. “There was some relief. You can see that in their residency in Boston, which started before Cale left but continued well after,” he says. “They were just a band again, led by a very singular artistic force, who was the auteur and there was no ambivalence or conflict around that. But even that wasn’t sustainable for Lou Reed and for whatever reason he needed to also end that and move onto the next phase of his life.”

It’s a perspective echoed by Richman, who saw The Velvet Underground live more than 50 times, including in his home city at the Boston Tea Party, and would go on to carve out a musical legacy of his own with The Modern Lovers. Describing the atmosphere at the shows during this era as “cosy and intriguing”, he remembers a group with few pretensions (and even fewer roadies), who would routinely congregate until the early hours at the nearby home of an English professor after playing.

“Local musicians, groupies, fashion models, actors, music writers, hustlers, drug dealers, photographers, cigarette smoke, cigars, pot, wine and liquor, loud gossip and, once in a while, the little record player would bring us a test pressing of a new Velvet Underground record, heard here for the first time anywhere,” he explained. “My ear would be pressed against the speaker and I couldn’t understand how anyone could gossip at a time like this.”

The widely despised Steve Sesnick, said to have schemed for Cale’s removal and pushed the group to continue even after Reed quit during their run of shows at Max’s Kansas City, is absent from recollections of their last days. Haynes says the production team had considered making contact but wanted to focus on The Velvet Underground’s “etymology”. In defence of their former manager, Richman, who slept on the sofa in his E. 55th St. apartment after befriending the group, states that “whatever other peoples’ experiences with him were, for me he was a very important person”, suggesting Sesnick had “more than a little of the mystic in him”.

In the final frames, the drone returns. Reed and Cale are pictured on stage alongside Nico, for a live rendition of ‘Heroin’ at 1972’s Bataclan reunion in Paris. It is the kind of elemental, emotionally taut collaboration that would, years later, produce the minimalist epitaph of Songs For Drella, the pair’s moving tribute to Warhol, on which Reed sang: “Fly me to the moon. Fly me to a star. But there are no stars in the New York sky. They’re all on the ground." First there is nothing. Then there is everything.

The Velvet Underground is in select cinemas and on Apple TV+ globally from October 15.