Charles Babbage is best known as the father of the modern computer, but he had other ideas, too. In 1838, the mathematician and mechanical engineer wrote about what we would later call “place-memory”, theorising that our voices and actions leave permanent but imperceptible imprints on the environment around us.

In the late 1930s, Henry H. Price, a professor of logic at Oxford, posited that objects may possess memory traces played back only when handled by those sensitive enough to perceive them. In his 1961 book Ghost and Ghoul, Thomas Charles Lethbridge, an archeologist turned parapsychologist, suggested that stone might act as a recording device that could capture and play back historical trauma.

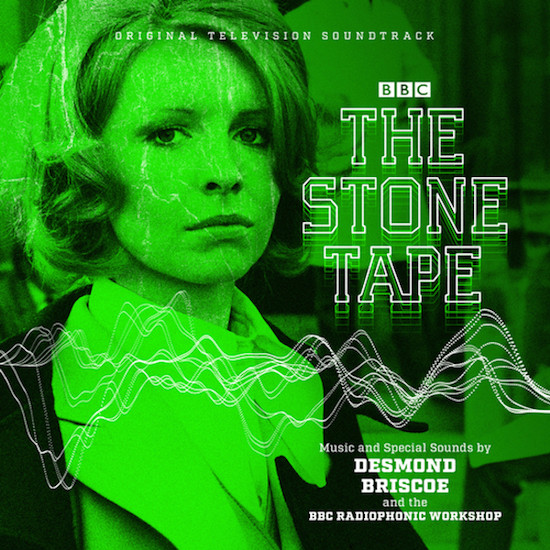

These are the foundations of the “Stone Tape theory” – ghosts are not wandering spirits, but lossless spectral recordings of past events made by our environment. The theory takes its name from Nigel Kneale’s The Stone Tape. First aired on Christmas 1972, the BBC teleplay tells the story of a mansion whose very building blocks are a memory bank for centuries of trauma, which scientists attempt to excavate by conversing with the stone.

50 Christmases since its release, it’s clear that The Stone Tape didn’t just popularise the idea of the “residual haunting”, it also continues to haunt cinema in various guises. Echoes of Kneale’s work are present in multiple contemporary films, rooting them to the same hauntological themes of sound, sentience and stone.

In Ben Wheatley’s phantasmagoric feature In the Earth, the first thing we see is a standing stone, the trees framed through its ‘eye’ as if we are viewing the world through its perspective. The framing is appropriate; the stone is alive.

Released and set in 2021 but suffused with a 1970s audiovisual aesthetic, the film follows scientist Martin (Joel Fry) and park ranger Alma (Ellora Torchia) as they journey into a forest with unusually fertile soil. Deep within the woods, they meet Dr Wendle (Hayley Squires), stationed there to study its mycorrhizal network. Likened to a “brain”, this vast fungal matrix controls the land from beneath the forest floor, and finds its nucleus at the ancient stone.

The menhir is linked to a local folktale, that of Parnag Fegg, said to be the spirit of the woods. Woodland wildman Zach (Reece Shearsmith) says Parnag Fegg is the spirit of an alchemist and necromancer hounded through the forest and “inducted into the stone”. Dr Wendle later produces a 15th-century book which says that, in the local dialect, “Parnag Fegg” translates as “sound”, “parnagus”, and “light”, “fegg”. Wendle doesn’t think Parnag Fegg was a person at all, but instead a process through which humans can communicate with nature. “There’s something in there [in the stone] and it wants to talk.”

The view through the stone in In the Earth. With this shot, Ben Wheatley pays homage to similar shots in Granada’s The Owl Service, 1969-1970

Whatever “it” is, both Zach and Dr Wendle are desperate to communicate with it. Zach tries to do so through faith and art, while Dr Wendle employs sound and light. She plays frequency sweeps through speakers to try to coax the stone into conversation. Here, the monolith’s hole begins to look not just like an ‘eye’ with which to view the world, but an ear with which to hear it, and a mouth with which to make noise of its own.

It’s also not unlike a speaker cone, the stone an instrument through which the entity within can ‘amplify’ human perception until it clips, triggering sensorial oblivion. When Alma is hauled shrieking from the cloud of mushroom spores released from the earth, Martin asks, “What did you see?” The answer: “Everything.”

Whatever Parnag Fegg is, whether it be Zach’s bedevilled necromancer, an ancient deity or the embodiment of the natural world, it’s responsible for a residual haunting through which its victims experience “everything”, everywhere, all at once.

Enys Men, the Cornish-language title of Mark Jenkin’s sophomore feature, translates to English as “Stone Island”. Set in 1973, the brooding 16mm folk film follows a nameless wildlife volunteer (Mary Woodvine) installed on an uninhabited Cornish islet to observe a strange flower.

As the story unravels, so does time and space. The past unfolds alongside the present, “everything” happening all at once. The volunteer sees her own memories projected alongside those of the land – Cornish lives long forgotten by its people but remembered by its soil. Once more, the locus of remembrance and ontological horror is a menhir, but this one’s more walking stone than standing stone – it seems to move of its own accord.

In her book High Static, Dead Lines: Sonic Spectres and the Object Hereafter, Kristen Gallerneaux explores the Stone Tape theory, and the popular idea of the ghost and its ties to sound and objects.

“The poltergeist, as a ‘noisy spirit’,” Gallerneaux writes, “is the most cut-and-dry example of the sonic spectre, where the concept of the ghost is absorbed and flattened into the tiny ontological space of the material, eager to manifest itself in order to be heard again.” In The Stone Tape and In the Earth, the scientists want to hear what it has to say.

One of the ways the haunting manifests in Enys Men is via the volunteer’s radio. Its broadcasts seem to be from both the distant past and the near future, as if the airwaves have been hijacked by ghosts in the machine.

The most interesting audio aspects of Jenkin’s film, though, are non-diegetic. Enys Men boasts the director’s signature post-synced sound. Gallerneaux writes, “When we record sound, we store time, archiving our own impermanence. When we are haunted by voices that stand outside of the exactly here and now, it is because we are being touched from a distance.” In Jenkin’s films, sight and sound are never quite in sync. The audio touches the audience from a different distance to the images, resulting in an unshakably uncanny feel.

It stands to reason that the further the distance, the stronger the signal. That is, the older the object, and therefore the older its memories, the stronger the haunting, or the more ‘past’ its handler is exposed to. In The Stone Tape, the characters reach much deeper into the past than they realise.

The BBC Radiophonic Workshop’s droning DNA can be heard in both the scores for In the Earth and Enys Men

Kneale’s teleplay follows a team of scientists searching for a new recording medium, who set up in a Victorian mansion. One of the rooms is supposedly haunted, and renovations within have uncovered remnants of an even older building: a stone staircase that leads nowhere.

As the scientists explore the chamber, they hear footsteps and screams. Jill (Jane Asher), a sensitive computer programmer, sees a vision of a young maid running up the stairs, as if hounded by some unseen force, and falling from the top to her death. Peter (Michael Bryant), the team’s headstrong leader, is sure that the stone itself is their new recording medium.

The scientists use audio technology to try to coax the stone – and, by extension, the past – into conversation, blasting the room with sound in an effort to trigger its playback and decipher its secrets. As in In the Earth, the stone only talks when it wants to, and is far older and more powerful than the flimsy scientists think.

The death of the young maid is dated to 1890, but it’s later revealed that exorcisms took place on the same site long before the Victorian edifice was built. The spectral phenomenon itself may be 7,000 years old.

In In the Earth and Enys Men, the sentient landscape literally takes root in the women at the heart of their stories. Jill is not so lucky. She eventually suffers the same fate as the maid, hounded up the stairs and to her death. But how could a fall from such a short height be so conclusively fatal? When Jill reaches the stairs’ summit, she finds herself somewhere else, at the mansion but also on the same land millennia before its first bricks were laid. Jill doesn’t just fall from the top of the steps, but also from somewhere deep in the past, the physical distance lengthened by the “distance” in time.

The mansion is built of Kentish ragstone. It’s the same greensand, we’re told, upon which much of mediaeval London was built. Kneale asks us to consider how many of the Big Smoke’s sightings might be attributed to such residual hauntings – endless death memories embedded in rock. The standing stones in In the Earth and Enys Men are older still, their histories entangled with ancient practices we know precious little about.

The ontological horror at the core of these stories is that the stone – which represents the natural world and the uses we carve out for it – is unknowable. It’s been here, affecting the land, whether erected as a monument or laid as bricks, for longer than we can fathom, and its inaccessible past has some frightening bearing on the present. Unlocking the secrets of these stones exposes the mind, audibly and visually, to thousands of years of recorded trauma. The stone tape triggers a cataclysmic playback that overloads the psyche. The ultimate reminder of our own “impermanence” is the vast archive of others.

The The Stone Tape’s end credits unfold over images of its characters superimposed on green stone, their tale eager to manifest itself in order to be heard again. Unlike the playback loops in Kneale’s story, however, his ideas are not “just a dead mechanism”. Fifty years on, they’re still being rediscovered, reprojected and reinterpreted. In the Earth and Enys Men are abstract, elliptical, and offer few answers. We never find out what spirits live in their stones, but of one thing we can be sure: Nigel Kneale is one of them.