There is a strange, empty promise with a certain kind of documentary film that audiences will finally be told the full story of the person who they are about to watch for 90 minutes. It goes against the definition – antiquated perhaps, but still true to some extent – that cinema thrives as a suspension of disbelief as much as an empathy machine. These films stubbornly say they will tell us everything the rest of the world tried to keep from us for so long. Except, too often, they fail miserably.

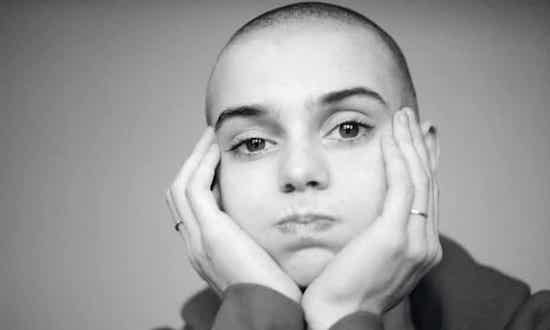

Three films premiering at this year’s virtual Sundance Film Festival leave a bitter taste once the inevitable post-film title cards (slow, silent, informative enough to prompt a tiny tut but not enough to actually gasp) tell us what’s still missing. The Sinead O’Connor documentary called Nothing Compares says it’ll chronicle “everything” – but what we get each time with that word is a scant recap of the headlines. The film does address O’Connor’s childhood in an abusive home with an unstable mother, her volatile relationship with the Church back when nobody believed priests could ever do such things, all the way to her infamous performance on Saturday Night Live in 1992 after which the world slowly started to realise that pop music and politics had always been uncomfortably intimate bedfellows.

But there is, through no fault of O’Connor’s (because in these situations, the subjects – and in this case, women – themselves rarely steer the final narrative so can be given little credit or blame), a painful omission that makes the film deeply infuriating. The song that gives the film its name, O’Connor’s 1990 release ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’ which features on her second album ‘I Do Not want What I Have Not Got’, isn’t heard in it. There’s a whole sequence discussing the filming of the music video, the way O’Connor knew how to cry, how that song skyrocketed her career – yet we never hear her sing it.

It’s revealed at the end of the film that O’Connor simply wasn’t given permission to use it. The song was originally written by Prince in 1985, and was released on his album ‘The Family’ – today, his estate barred O’Connor from playing her own version in her own film taking the name of her own megahit. There could be a few reasons for this – as O’Connor addresses in her 2021 memoir ‘Rememberings’, the circumstances under which she and Prince met were murky. There were claims of a “sexual tantrum”, which led O’Connor to write: “I never wanted to see that devil again.”

But of course, none of these facts regarding O’Connor’s relationship with Prince feature in the doc (which, as much as it claims to be exhaustive, doesn’t even say the song isn’t hers). In fact, a lot of other facts of O’Connor’s life are left out once it became a little trickier to neatly retell them. Yes, O’Connor started finding her voice as an activist and a woman in the 1990s, but she sure as hell carried on using it through to the present day – yet the film skims over everything that happened after SNL, offering instead a smash cut of female popstars deemed outspoken or inspirational in ways that O’Connor first shocked the world all those years ago. It’s lovely, but it’s also going against who she really is by omitting so many milestones.

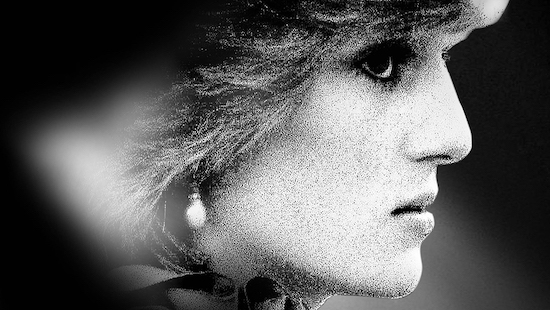

The Princess has the opposite problem. Coming only a few months after Pablo Larraín’s woozy biopic Spencer, Emma Corrin’s award-winning turn in season four of The Crown and the arrival of the wretched Broadway show Diana: The Musical on Netflix, writer-director Ed Perkins claims his archive-led documentary will offer “a bold and immersive” narrative of Diana’s life. But the result, instead, is pretty vulgar – going over and over all the footage we’ve already seen on the news in the last four decades and in fiction in the last few years.

Of course, that probably is the point – make the public really regret the way they treated Diana and the way it drove this poor woman to tragedy. But is this really the best way to honour her? It tries to dig up all these invasive shots and poke those uncomfortable interviews and go over and over and over the words you know she said and have tried desperately to decode in order to understand why her life ended the way it did. Except none of us can do that, and none of us should – The Princess feels like some kind of fictionalised true crime story, a voyeuristic binge in which the people are so far removed that they exist purely to entertain and confuse those who stumble across it. It’s treating people like characters, their lives as stories.

She was one of the most photographed women in the world, and everyone will surely recognise all the footage in the film. So what are we doing here? Just offering a neat shortcut for those times when you would like to reopen the conspiracy group chat? Perhaps, but the documentary form once more is weaponised here, robbing a woman of her agency by stitching together all the public scraps of life we have in order to offer some kind of upsetting recap just how much Diana was wronged. The cycle, somehow, still continues.

One woman taking more control of her own story yet still somehow bound to a man who ruined so much of her life is Evan Rachel Wood. In the two-part HBO documentary Phoenix Rising Wood speaks to camera about the abuse she suffered at the hands of Brian Warner, better known as Marilyn Manson. The film does a good job of trusting her memories and giving a platform to the stories she had been silenced on for so long, yet it also gives a strange amount of airtime to Manson’s voice as well.

Time is split between talking heads interviews and bizarre storybook animations defining a lot of the trauma Wood suffered. “Lovebombing” and “isolation” are written out in austere, cursive letters as the pages turn in this make-believe book framing the true facts like dangerous but sexy fiction. It gets more unnerving, too, when Manson’s words from journals and other pieces of writing are read out loud by an ominous male voice – not his, sure, but not Wood’s either.

The actress remembers so much of her time with Manson and tells these stories with breathtaking calm and control, and so to then shift the control back to him, to an extent, to bring him to life like some kind of Disney villain, feels a little tone-deaf. If Wood is happy with this, fantastic, but the message it’s giving “provocative” artists and men bending the rules and pushing the limits of what they can get away with (if you have to wonder where the line is, you’ve probably already crossed it) is deeply uncomfortable.

There is, of course, no one way to tell a woman’s story onscreen – particularly any one (so, anyone) with a complex story that will never be able to fit into a tidy runtime and pleasant package that entertains as a priority and maybe sets the record straight as a bonus. But there are, regardless, things that can be avoided – voices to be prioritised, battles to be fought, some silences worth respecting. When, if ever, will we finally learn?