Romain Gavras has built an epic. The acclaimed French director of music videos for the likes of Kanye West, Jay-Z, MIA and Jamie xx is back with his third feature film Athena – a Greek myth-inspired story of three brothers in the aftermath of the murder of their youngest sibling, apparently at the hands of the police.

With immersive long takes of chaos and uprising in the Parisian banlieues, Gavras matches his visual verve with searing commentary on racism, inequality, fake news and police brutality. He talks to The Quietus about the inspiration for Athena, its stunning 10-minute unbroken opening shot, the legacy of La Haine and the influence of his parents.

The Quietus: You’ve explored a lot of images of unrest and riots before such as in the ‘No Church in the Wild’ video, are these themes you’ve been wanting to tackle for a while?

Romain Gavras: Yes, they are themes I keep coming back to because in France my true education is the iconography of the French Revolution. And in Greece, the same, from the Trojan War. So I guess there was some kind of obsession where some of the music videos were more like poems or singles, and Athena is more like the album which we wanted to structure around a Greek tragedy narrative and explore it more in depth.

So was the origin for the idea from the Greek myth and wanting to put that in a contemporary situation?

Yeah, when me and Ladj Ly [director of Les Misérables], a childhood friend of mine, started writing, it was around the idea of the spark that could ignite the fire in the French nation. And to be inside it, to start from the intimate pain of a brotherhood that gets torn apart and their pain and their way of grieving and rage and how it’s going to spill over the neighbourhood and over the nation.

Most films set in the banlieues or estates are often very gritty, very realistic, and obviously Athena is not that. Was it more interesting to you to explore these ideas with very stylistic iconography?

When you make a film, you want to bring something to the cinematic table, the way you’re going to tell the story and the way you’re going to articulate it visually. And so to put it in a Greek tragedy way was to make it timeless so the idea that it’s happening in a French state, but it could have happened in mediaeval times. We had visual cues for that, we turned the estate almost into a castle and built turrets on it. The idea was that this is happening in France, today or tomorrow, but it has the same architecture of the way a war can unfold from the past or in the future.

Can you talk a little bit about the logistics of the opening scene? Was that all done in one take? Or did you do several and they were digitally stitched together?

I’m like a magician, I never reveal my tricks! There’s no CGI in the film, the crowd is real, the fireworks are real, everything is done mechanically. For example, in that scene, we go from outside the van with the camera on the motorcycle, passing it inside the van, so the idea was to do everything very practically. It’s harder for the actors with the movement of the camera and the long takes.

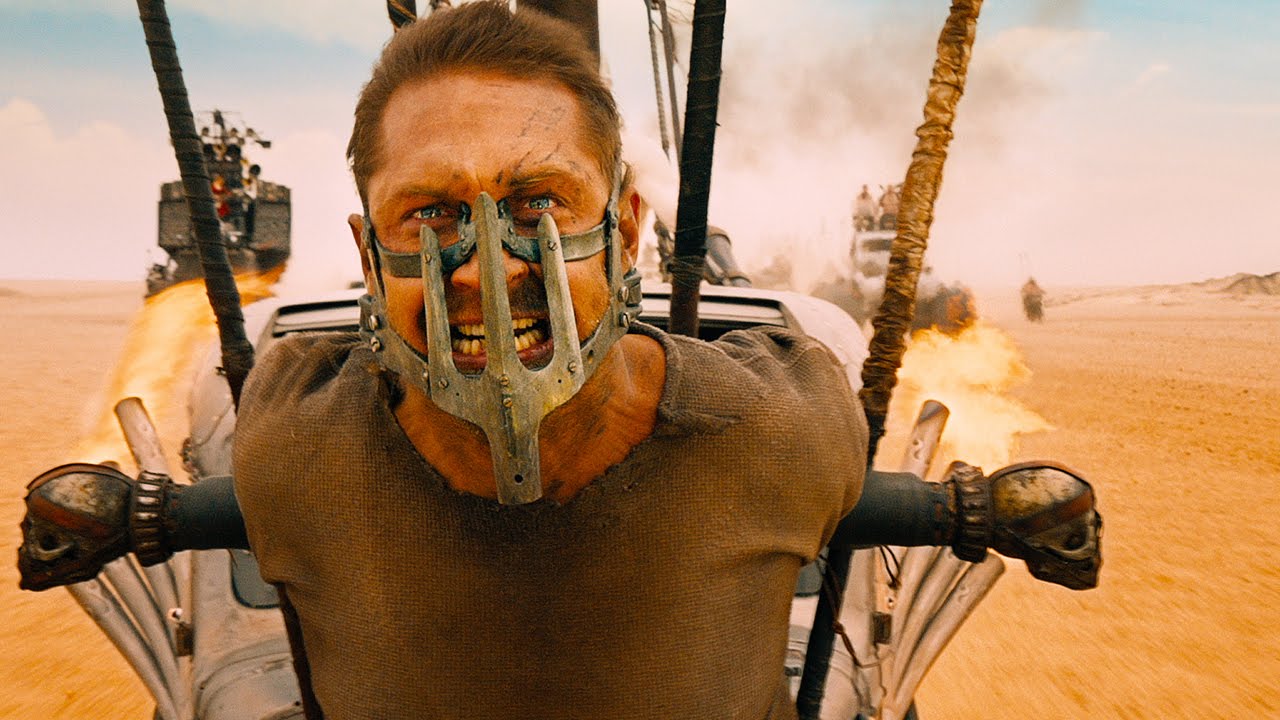

In some respects, Athena reminded me of Mad Max: Fury Road with how immersive it is. What were some of the visual places you were pulling from?

From a lot of places, from paintings to Kurosawa to Apocalypse Now. What I liked in Apocalypse Now is that it is about the Vietnam War but it’s bigger than just Vietnam, Coppola made it timeless and we had a lot of references to that. Kurosawa’s Ran was a good reference because everything was done mechanically, like the castles burning and it’s the Bible for long takes. Back in the day they did it with cranes, and we wanted to make it like this with no green screen.

One of the most interesting things was the tension between the three brothers, which seemed to emulate a lot of real world tension with families stopping speaking because somebody voted for Le Pen or Trump or Brexit. What do you make of that?

Yeah, it was the thing with civil wars, and Greece has had a big share of civil wars for some time I hear the stories even in my own family during the Greek civil war that was happening just after the Second World War. It’s horrible, because it’s the worst kind of war because it’s families against families. It was grandfather against grandfather. It was interesting here to see the conflict in the nation, but also operating from within the intimate conflicts within a family where no one listens to each other and their way of grieving is going to be completely different and antagonistic.

Can we talk about the ending? The war, so to speak, was built on a lie. The kids don’t believe the news – these seem very pertinent ideas at the moment.

The idea around the film was distrust in the media and how fragile a country like France can be and how easy it is to manipulate a situation that’s already tense. And how easy it is when a situation is tense like this, to push the nation over the precipice. But it’s also a timeless idea, like almost every war started with a lie from the Trojan War to Colin Powell. There’s always forces, whether it’s the government, whether it’s darker forces, or more discrete ones pushing for people to fight on the ground.

Were you tempted to leave it ambiguous?

I always had a strong instinct that it had to be in it because I feel that it is more tragic to end like this because it has a pessimistic kind of feeling. I think it’s also more coherent with the theme that with the fragility of a country and a situation of conflict, there are always people that thrive on chaos, and that are pushing towards chaos.

Does that pessimism reflect the way you see France and the world at the moment?

The thing is, there are always bad things happening all the time, all over the world so every moment that we are in, we think, “Oh, it’s going bad”, but it’s been going bad since the prehistoric ages. The thing is though, it’s very difficult these days to see optimism. You don’t have it like you had in the ‘70s, for example, a movement towards an optimistic future like the generation of my father, they were probably more optimistic at my age and had optimistic views.

This is probably the closest thing you’ve made to something like your dad – Oscar-winning filmmaker Costa-Gavras – made, did that dawn on you at any point?

I’m a huge fan of my father’s films. I feel like I had to wait to have the right maturity with my craft to go there, because when I put a film like this out there, I’m also carrying the name with me. If I fuck it up, I not only fuck up myself but the name as well. I guess I had to feel ready before going and making a film like this.

Your mum was also a great journalist, she was in Vietnam and in Bolivia with Che Guevara. Was a lot of her in here as well?

There’s a lot of my mum in everything. There is a lot of power from her, in the sense of the way I was educated to see the world and the way I was brought up.

In a leftist house sense?

Yeah and in a way of seeing the world that’s not obvious. When kids were watching Disney, as a kid I was reading Greek myths with stories about a mother strangling her children, so that’s always been fed to me in my brain.

You’ve obviously made a lot of great music videos, music was a big part of your previous feature The World is Yours with the Jamie xx tracks. Can you talk a little about the score of Athena which sounds so huge?

Even when I’m writing, I need to have a sense of what the music is going to be like because it’s the way my process works. So we had very strong themes from the beginning, and we wanted to carry themes which come from music from our friend DJ Mehdi, who passed away 10 years ago.

We took a few of his songs and kind of like, translated it into philharmonic music with orchestras and Greek choirs. All the lyrics are in Greek, sung by Greek choirs. Part of the movie we really constructed like an opera or even in Greek tragedy, you always have those choir effects that are singing what’s unfolding before your eyes.

Can it be hard to escape the legacy of La Haine when making a film about the Parisian banlieues?

No, because I was 14 when La Haine came out and Mathieu Kassovitz was a neighbour from upstairs, and even more than my family, that made me want to do cinema more. The legacy is a blessing but the culture from those neighbourhoods is the mainstream culture in France. Maybe from outside of France, it can be seen as niche and La Haine is obviously the biggest one that has come out. As a filmmaker, the question is: how do you renew the way of telling a narrative and telling a story in that territory?

So was Mathieu Kassovitz a big influence on you?

Yeah, growing up, he was definitely a big influence. I was a teenager in the ‘90s. So, you know, it was from La Haine to the Wu-Tang Clan, to Spike Jonze music videos to Chris Cunningham music videos so it was a mix between these and films I was forced to watch when I was younger like Tarkovsky and Kurosawa.

Jean-Luc Godard died last week, how did he inspire you?

He was a big influence in the way he talks about cinema because there was no one better in France to talk about images and talk about cinema. He made insanely interesting films in terms of how free you could be with narrative, especially in Pierrot le Fou, but what is really impressive is the way he talks about cinema.

Athena is on Netflix now