Almost exactly 100 years ago, F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu helped establish the vampire as one of the iconic antisemitic stereotypes of the 20th century. As the undead villain Count Orlok, Max Schreck was thin, stooped, and pale with an enormous hooked nose, a long black coat, and an odd skull cap. He was a twisted Jewish caricature – a parasitic, invasive outsider who fed on the blood of noble Christians.

Today, the vampire remains one of cinema’s most popular horror villains, and the connections to prejudice are largely forgotten, or erased. They still lurk around the edges of the genre though, as generations of creators have either furtively invited them in or tried to put a stake through their heart. In part, Nosferatu remains relevant not despite, but because of the hatred at its core. It’s a horror which continues to stalk us, but which the vampire myth may also provide us with some resources to dispel.

Nosferatu faithfully suckled on antisemitism, but it did not introduce it into the vampire myth – that was Bram Stoker’s doing. His 1897 book Dracula,scholars believe, was partially based on the antisemitic 1894 novel Trilby, in which a Jewish villain seduces and abuses European girls. Stoker described Dracula himself as having an “aquiline” nose, pointed ears, and “bushy” eyebrows – all staples of antisemitic depictions at the time. In fact, Dracula looks rather like his own human agent, Hildesheim, who Stoker says was “a Hebrew of rather the Adelphi Theatre type, with a nose like a sheep, and a fez.” (Stoker is probably referencing Petit and Sim’s London Day by Day, a particularly vicious antisemitic play which was performed at the Adelphi.) Stoker’s heroes bribe Hildesheim for information, because he’s Jewish, and Jews are supposedly greedy – for money or, in Dracula’s case, for blood.

Murnau does not seem to have been antisemitic himself, and the film’s scriptwriter, Henrick Galeen, was Jewish. But Nosferatu’s powerful visuals and streamlined plot faithfully conveyed Stoker’s bigotry and added an additional expressionist bite. Hildesheim was combined with Renfield, Dracula’s thrall in the novel, to create the estate agent Knock (played by Alexander Granach, a Jewish actor). Knock is a cackling, grasping, bushy-eyebrowed money-grubber, who descends into madness and murder as his master draws closer.

Orlok himself is a terrifying avatar of invasion and infiltration. One of the film’s most powerful sequences sees his ship journey from Transylvania to the German town of Wisborg. Orlok travels in coffins filled with rats, and murders the sailors one by one. Once he arrives in Germany, plague breaks out, and he fixates on Greta Schröder’s Ellen Hutter.

In the final sequence of the film, he enters her house, doors opening magically before him, before feasting on her neck, dramatically portraying antisemitic fears of perverse sexual exploitation and desire. Nosferatu deftly links medieval conspiracy theories about Jews deliberately causing the Black Death and blood libel about Jews using Christian children’s blood in their rituals, to more modern conspiracy theories about Jews as immigrant infiltrators undermining social cohesion and sexual purity.

Stoker and Murnau ensured that the idea of the vampire would be infected with antisemitism, and vice versa, for many years to come. Adolf Hitler in 1925’s Mein Kampf refers to Jewish people as vampires and bloodsuckers, and calls them “that race which shuns the sunlight.” In the 1931 Dracula, starring Bela Lugosi, the titular vampire first appears wearing a large star of David necklace, identifying him as Jewish, and/or comparing the undead, blood-sucking monster to Jewish people. The vicious 1940 Nazi propaganda film The Eternal Jew, picks up numerous tropes from Nosferatu, according to scholar Eric Rentschler. That includes most vividly its equation of Jews with vermin and rats, and its charges of sexual predation (The Eternal Jew makes the outrageous false claim that Jewish people controlled 98% of prostitution worldwide.)

The teeth of antisemitism are difficult to dislodge, and bigotry continues to haunt vampire legends in odd and unexpected ways. For instance, in 1986’s Aliens, Paul Reiser plays a greedy, oily corporate shill, who provides victims to the vampiric aliens who both feed upon and breed with human beings. Reiser, like Alexander Granach before him, is a Jewish actor playing a stereotypical Jewish character who betrays his own race to a horrifying monstrous other. You can hear Knock’s cackle echoing, faint but discernible, through the decades.

Other vampiric variations, though, have subverted – or at least rethought – the negative association of vampires with evil outsiders, and by association with Jewish stereotypes. Richard Matheson’s novel I Am Legend, for example, imagines a post-apocalyptic world in which vampires have conquered the world. In this context, the lone human survivor, murdering vampires relentlessly, becomes the outsider and the threat to communal cohesion. In a concluding twist, he realises that the vampires are the protagonists while he is the villain of the piece. The novel doesn’t exactly challenge the insider/outsider vampire dynamic—in the end, there remains no possibility of racial détente, and the only solution to difference is genocide. But I Am Legend does ask readers to consider the possibility that vampires, those disgusting, Jewish-coded outsiders, might be worthy of sympathy after all.

Matheson built on the idea, implicit in Stoker, that if humans can turn into vampires, then vampires are humans, and vice versa. Stephen King developed that idea further in his 1975 book Salem’s Lot. The novel is about a normal, small, good American town infected with vampirism, quickly revealing its underlying cruelty and horror. “There’s little good in sedentary small towns,” King writes. “Mostly indifference spiced with an occasional evil – or worse, a conscious one.” The cheerful purity of Wisborg is turned inside out; the vampires aren’t evil Jewish invaders so much as pious, bloodthirsty Christian neighbours coming home. “When the evil falls on the town,” King writes, “its coming seems almost preordained, sweet and morphic.”

For King, if anyone can become the Other, the Other is everyone, which means humans are the real monsters. Other creators have instead made the monsters into the real humans, finding ways to sympathise with or at least express a fascination with the vampire.

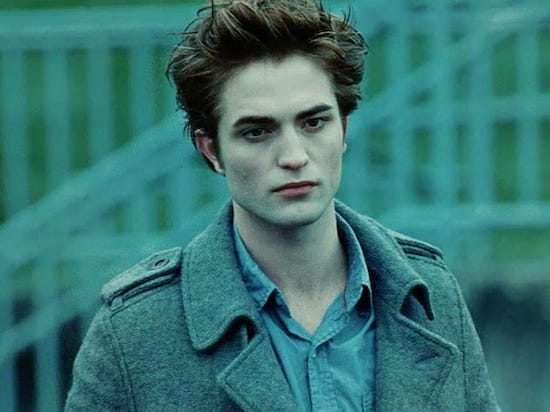

Post-Orlok vampires were often more attractive than the caricatured Count. The Dracula of the British Hammer horror films in the ‘50s and ‘60s, Christopher Lee, radiated a brutal but effective sexuality; the women he ravished tended to express at least as much desire as horror. Along the same lines, Werner Herzog’s lush 1979 Nosferatu remake presents the Count as, in the director’s words, “not a monster, but an ambivalent, masterful force of change,” who upends the staid bourgeois German town with the twin anarchic levers of sex and death. And then there’s Edward in Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight series. He’s a vampire superhero sparkly elf, whose non-humanness and dangerous strength and power just make him more completely the perfect romantic lead.

Meyer is Mormon, and Edward’s theological concerns – he believes in souls, in heaven, in hell – are situated firmly in that religious context, rather than in Judaism. That’s typical: as vampiric portrayals become more positive, they tend to also become less connected to Jewish representation.

The title character in Bram Stoker’s Dracula, for example, is noble and romantic in part because he’s a cursed Christian knight, who renounced God in grief over the loss of his true love. The narrative hinges not on fears of Jewish infection and invasion, nor on stereotypes about Jewish greed and bloodlust, but rather on Christian notions of chivalry and redemption.

There are narratives which specifically embrace the connection between vampires and marginalised identities – but the marginalised identities in question are rarely, if ever, Jewish. 2008’s Let the Right One In, reverses the hatred and fear of queer sexuality embedded in vampire stories; it instead provides a sympathetic portrayal of a persecuted trans vampire character. Ganja and Hess (1973) and Blade (1998) connect vampiric legends to stereotypes about Black addiction. And there are a slew of lesbian vampire stories, in which forbidden sexuality is portrayed with varying degrees of sympathy and prurience.

Many authors, then, have recuperated vampires by making them less marginal figures. Many have recuperated vampires by embracing the marginalised. But virtually no one has responded to the antisemitism of Nosferatu by trying to recuperate the vampire as a Jewish hero.

That’s understandable. Count Orlok is a grotesque figure, and the retroactive association with Nazi propaganda makes it particularly difficult to reimagine him in a positive, specifically Jewish context. Most creators have reasonably concluded (consciously or otherwise) that the best way to handle the vampire/Jewish connection is simply to pull its teeth. Tell Jewish stories without vampires; tell vampire stories without Jewish people or characters. That’s the safest way to go.

But whether or not you ignore the Jewishness of vampires, Nosferatu won’t die. It’s still there, still hugely influential, still antisemitic, and still strange and beautiful and great fun to watch. So if you’re Jewish, how do you enjoy a film that so clearly hates you?

Given the history of vampire revaluation and revisionism, one way to watch Nosferatu as a Jewish vampire fan is to root for Orlok. Obviously, he’s ugly and repulsive. But (as every vampire fan knows) repulsiveness and attraction aren’t that far apart.

Ellen and Thomas Huttler, the righteous German supposed protagonists, are aggressively, irritatingly bland. Thomas laughs with mouth agape as if he’s trying to convince himself of his own good cheer. He kisses his wife with sexless enthusiasm, and then trots off to Transylvania in pursuit of money, chuckling at local legends of vampires along the way.

It is only when the Count pulls up in a magically, disturbingly rapid coach (filmed at faster frame speed) that the film grows a distinctive nose and becomes compelling. Thomas virtually vanishes when the angular, mordant Orlok is on screen. Even the vampire’s shadow, cast upon the bed, is more real and alive than the simpering estate agent. The Christians are dull, dead, nonentities. Orlok is doing them a favour by bringing a bit of his foreign soil to their drab corner of the world, not to mention a taste of his humour. (“Your wife has a lovely neck.”)

In addition to humour, Orlok is cloaked in sex. Supposedly, Ellen is hypnotised by Orlok, and/or welcomes him to her bed in order to trap him into staying up to the cock crow, so the first light of the sun will disintegrate him.

But if you look past the anti-Orlock propaganda, what you’ve got is a bored housewife with a thoroughly unstimulating husband throwing open her windows when she sees that odd, magnetic face at the window, with its long nose and those insinuating, lengthy, eloquent fingers. He doesn’t sneak in, but enters triumphantly. The Jewish Orlok gets the girl.

It’s true that Orlok and Ellen both die at the end. But is that because their union is cursed by God? Or is it because it’s cursed by someone less divine? When Orlok fades to nothing in front of the window, you’re arguably seeing an erasure, not of the vampire’s evil, but of the evil done to him because he dared to love outside of the Christian laws of blood. The punishment for crossing borders of religion, of nation, of romance, is death and demonization. We’re supposed to think Ellen was brave for enduring Orlok’s kiss in order to destroy him. But maybe she, and he, were simply brave for loving each other when they knew the consequences.

Orlok isn’t intended to be the hero of Nosferatu; he’s not even intended to be an antihero. But a century on, without many Jewish vampires to call our own, I think it’s time to embrace that weird immigrant count who, with that nose and the eyebrows, looks at least a little bit like me. Nosferatu is not a movie that welcomes me in. But Count Orlok, in the best traditions of the diaspora, refused to stay in the box the gentiles built for him.