Writer-director Mark Cousins describes himself as an activist. His latest 14-hour documentary, Women Make Film: A New Road Movie Through Cinema, which will be released in five episodes on the BFI player, is already making waves around the world. It’s an empowering, affirmative piece of work which will help rewrite a male-dominated film history. Which directors spring to mind when we think of the greats? Tarkovsky, Kubrick, Welles, Fellini… Google it and you get just that, over 50 male directors, the majority white. But Women Make Film tells a different story. Since the birth of cinema, women directors from around the world have been making bold, innovative films that have been forgotten or underexposed. Using film clips from 183 women directors spanning five continents and 13 decades, it’s shocking and eye-opening to watch extracts of films that are not, but should be, iconic scenes from household names. Instead they have been all but erased by what Cousins calls “sexism by omission.” Speaking to Cousins on the phone from his house in Edinburgh, I find his voice is lyrical, soft and kind. We are discussing his passion project, which is set to reinvigorate a global interest in women directors and their rich heritage.

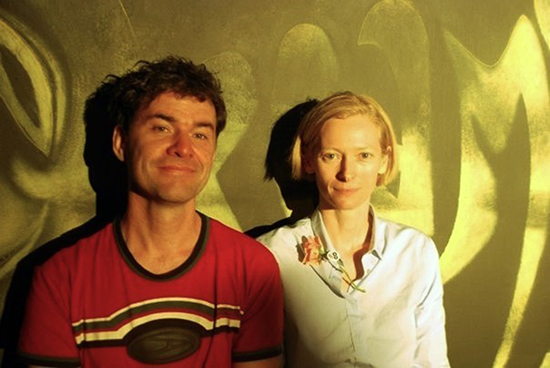

Showing more than telling, Women Make Film, narrated by Hollywood heavyweights including Jane Fonda, Tilda Swinton and Thandie Newton, doesn’t pontificate about why these women directors haven’t been written into film history, neither does it try to draw generalised ideas about ‘women’s cinema’. Cousins explains his approach: “My hunch was not to talk about the female gaze, not to ask how women make films differently, to take a sort of androgynous perspective.” Instead, the documentary is almost a ‘how to’ filmmaking guide. How to film openings, how to film bodies, sex and sci-fi, regardless of your gender. Cousins tells me, “This is an affirmative piece of work, we don’t mention Weinstein, we don’t talk about these women as victims, I think to do so would be to re-victimise them in some way. It’s saying, look at their work. So many people have written women out of movie history, but it’s never too late.” It’s moving to hear a male director care so much about women directors, so dedicated to shaking up the film industry and the old boy network simply by showing the work of women directors in his new film. After making his similarly epic documentary, The Story of Film: An Odyssey, Cousins wanted to go further, and decided to dive back into film history to look for more great female directors.

Cousins tells me a moving story from the world premiere for the film at Toronto International Film Festival, about a woman who came up to him after the screening. “I’ll often say I don’t want to do a Q&A but I’ll be in the pub,” he begins. “Lots of people show up after 14 hours and they’re crying, there’s a lot of tears. After the world premiere, this young woman said to me, ‘I thought I was alone.’ I’m going to get upset thinking about it. ‘I didn’t realise that I was part of a great heritage.’” From the first ever woman to direct a feature film and founder of a successful film studio in the US, Alice Guy Blaché, the striking and prolific work of Ukranian filmmaker Kira Muratova, to the pioneer of PanAfrican cinema Sarah Moldoror, Women Make Film sheds light on a whole host of critically overlooked directors who have been making an impact on the cinematic landscape since its genesis.

A turning point in Cousins’ career came when he made a programme of films for the Edinburgh International Film Festival. “In the mid 90s I did a big series called Great Moments in Documentary History and as soon as we did it, I realised there was only one woman director in there. I resolved not to make that mistake again. Since then, for 25 years, I’ve been keeping a mental list in my head of the filmmakers I’d been learning about,” Cousins confesses. We discuss the idea of how an unconscious bias in awards ceremonies, in film courses, in popular culture, perpetuates the erasure of women filmmakers from the bigger picture. Cousins mentions the meme going round, which imagines six rooms with different filmmakers in each, asking which room you want to spend more time in. “It’s Scorsese and Tarantino… 25 filmmakers, two women. And the people who make that, they aren’t thinking ‘Oh let’s put as few women as possible’, they’re just not noticing.” We discuss how education is the key to creating more awareness around the vibrant film history of women directors around the world. Cousins says, “That’s where the revolution can happen. Every film school has to rewrite their film courses to include a lot of these female directors. It’s not enough to have Varda, it’s not enough to have one film by Jane Campion. I’m sorry, it’s no longer enough.”

Film courses around the world are already starting to take note, just as they did with Cousins’ last documentary. “I’m sure I’ve heard from 40 film professors saying they’re going to change their courses,” he says. TV stations across the globe are also embracing Women Make Film. “It’s already played in a single 14-hour event on Spanish TV. It had quite a big impact in Brazil. A Finnish TV channel bought over 100 films directed by women to show with it. Something similar will happen in America later this year,” Cousins tells me. But Cousins has little patience for complacency. Even if TV, streaming services and film courses are not doing their duty to showcase talent from women directors, he wants everyone to make their own discoveries. “We can point the finger at the gatekeepers, the storytellers who are mostly men, but we also have to blame ourselves a little bit,” he says. Cousins believes we are all responsible for our own knowledge. “I’ve met a lot of activists, passionate people, women and men, who care about feminism who are arguing for change in film culture and in the film industry, and of course I am on that barricade with them, but it’s surprising to me how often they haven’t seen many of the films,” he says. “It’s almost like our anger at the sequestration of women means that we are blinded to the past, or we think it’s not worth digging back in the past of film history because there’s not much there.” He adds, “It starts to sound a little bit empty to me, if we are only activists, and I repeat, I am an activist, I want to change the film industry as fast as possible, but surely, surely we need to know the shoulders on which we’re standing.”

Worse than the erasure of women directors from film history is the intentional spreading of misinformation, like the new Netflix show Hollywood, which imagines Hollywood’s first female studio boss. Cousins explains his frustration with the show: “You think, hooray, how great! Except there were female bosses who ran movie studios from 1910. Alice Guy, who has the last image in my film, Alice Guy set up and ran an American film studio in 1910. Mary Pickford set up United Artists, which still exists, in the silent era. Astor Nielsen in Denmark set up a film studio. So, I could name at least four women who ran film studios.” Yet people around the world who watch the show will be led to believe that women didn’t run the show. “You are victimising and erasing these women if you don’t refer to them. So many millions of people watch this series because it’s a huge hit. And they will all be misinformed,” Cousins laments.

But Cousins isn’t anti-Netflix. He sees its appeal and likens it to the 1950s, where there was “a kind of Eisenhower era of optimism.” He describes its allure, “The people are pretty and the clothes are beautiful and everything is very bright, and that’s fine. I like escapism. I love Hollywood musicals and things like that. But it means that there’s quite a lot of the lived spectrum that you don’t see.” With his fondness for the epic form, Cousins leaps into big subjects in such a way that will attract wide audiences. He tells me how he made a conscious decision not to take an academic approach with Women Make Film. “That means that somebody like my mum, who left school at 14 and didn’t benefit from an education, hopefully she can sit and watch this because there’s no assumption of major prior knowledge or theoretical concepts. It’s very much born from the idea that film is an accessible medium, regardless of your educational attainment or something,” Cousins says. Whilst the irony of a male director releasing such a film hasn’t gone unnoticed, this is not a producer coming to a director with a commission, this is a writer-director’s passion project, the fruit of years of labour. Cousins explains, “When you’ve got a head full of knowledge about something, or rather enthusiasm about something, it starts to feel like a pressure cooker. And at one point, I just thought, I think I’ll do it. You know, what’s the worst that can happen?”

We turn our conversation to the current pandemic and the future of the film industry. Is Cousins worried? “There will definitely be collateral damage. Careers will be damaged. Careers will be ended. Cinemas will close. Beloved cinemas will close. So, there’s going to be a lot of hardship and a lot of damage.” But he is ultimately optimistic for the future, and we end the interview on another affirmative note. “We’ve all noticed that the taste, the hunger for cinema and music and culture has not gone away. If anything, it has increased in the time that we are isolated,” he says. “People are desperate to go back to the cinema. So, after the rough rapids, the theatrical experience of seeing something bigger than life will continue, probably in a slightly different form.” Whilst the entertainment giants like Amazon, Netflix or Disney may buy theatres, Cousins says, “This theatrical experience will come back with a bomb, as our desire for cinema has not been lessened by the lockdown.” Calling cinema “an androgynous, anarchic rectangle”, Cousins’ new film will make every feminist, every activist, every person who loves film, want to dig that little bit deeper, to educate and share the knowledge about the rich and vibrant history of women making films.

Women Make Film: A New Road Movie Through Cinema is released on BFI Player and on Curzon Home Cinema from 18 May.