We live in an era of Internet domination, where most of our relationships exist at least in some part online – so it only makes sense for films to try to sort through this new way of interacting. At this year’s London Short Film Festival, there was a theme that echoes throughout the entire program about the digitally mediated body. By creating narratives that give the appearance of happening entirely online, filmmakers are adopting elements from the found footage horror genre, particularly with techniques seen in features such as 2014’s Unfriended and last year’s Host. Text messages, Instagram stories, video snippets and more are layered on top of each other to create a collage of our current state of intimacy. By navigating an idea of footage discovered online and what these small clips can tell us about interpersonal relationships, filmmakers are establishing a new method of filmmaking that weaves personal tales of love in the age of the Internet.

In the fictional short film 7 Bananas, the story is told almost exclusively through screen recordings of text conversations, short videos from Instagram Stories, and live streaming video. A teenage girl is scrolling through this content as she reflects on the death of her best friend, who committed suicide for reasons never explicitly stated. The night before the friend committed suicide, she tried to reach out to her friend, looking for solace and comfort. But the teenage girl ignores the texts. She reads old messages to relive their final conversation, thinking about how she could have better responded to avoid this tragedy. She watches old videos to remember drunk nights at house parties. The amalgamation of media creates a bigger picture of their friendship, both public and private. While online they may seem like the best of friends who loved to be the center of attention, their one-on-one conversations imply a more fractured relationship. Intimacy, then, becomes performative.

7 Bananas address intimacy both between the two women and between viewer and film. Viewers are given access to this private relationship, as they watch as voyeurs. The digital exchanges between the two women act as a memorial to their friendship, a strange intangible aggregation of emotions that the viewer can only hope to decipher.

Mango also dissects the politics of intimacy between characters and viewers, as we are given access to the private life of a young teacher engaging in an affair with a man named Luke – the way they met is not explained. Her life is shown through her front-facing camera, documenting her daily routine and a sense of dissatisfaction with her life, also communicated through messages exchanged with both her boyfriend and her new lover. Instead of dialogue, the woman is shown quietly watching BDSM porn while her boyfriend sleeps. Nudes from Luke pop up on her phone. Her passionate and clandestine sex with Luke, again filmed on her phone, contrasts with her droning routine. The viewer observes her life as if sitting in her front-facing camera, collecting pieces of evidence to understand her private relationship with intimacy in a digital space.

While 7 Bananas and Mango utilize digital interfaces to build complex pictures of how relationships span across platforms, Sisters offers a stripped-down look at the difficulties of grasping onto familial relationships that can only exist over Zoom, in the time of COVID-19. Three sisters discussing how to care for their ailing mother sit on separate screens. The images of isolation allow the viewer to focus on the relationship between the three sisters, but also lets us into their homes. While that access is limited to the screen, their living space is still visible, from offices to bedrooms. For one sister, it shows her wealth. For another it shows the chaos of a home filled with children. It establishes that despite a contrast between all of their lives, they still love each other. Their love transcends socioeconomic status. Beyond domestic spaces, Sisters offers a snapshot of a seemingly familiar yet important conversation, placing emphasis on how the smallest things should be treasured. Methods of communication have so drastically shifted in the last year – it’s not as simple as three sisters meeting for lunch. Instead, their love and care have to be shared through pixelated video images, which now evoke their own type of intimacy: full of longing, but also relief to still be able to achieve some sort of connection.

Isolation has also given many the time to reflect on the past and how we want to preserve that, if at all. It is a time of introspection, and what better way to piece together your personal history through the re-discovery of past images and videos? Non-fiction films Aqui y Alla and Echoes of Difficult Conversations During Lockdown are prime examples of using the pandemic to reflect on buried personal histories that bubble to the surface during periods of solitude.

Just as the fictional short films layer different media to create a deep viewer-character relationship, Aqui and Alla uses the Google Earth interface to navigate the meaning of home. In utilizing this technology, director Melisa Liebenthal is able to discover images of her past – not unlike a found footage film. She also uses old black and white maps as well as archival photos, marrying digital and analog means to bridge the gap between traditional ideas of found footage and new concepts of digitally discovered footage. In an attempt to understand her own identity, Liebenthal builds a tension between birds-eye-view images from Google that create distance, and the personal portraits of past family members. The film offers a meditation on how close the Internet may allow someone to feel to their family, while still showing a certain disconnect as the images on screen are not always tangible. Information is crucial, but it cannot mimic physical intimacy.

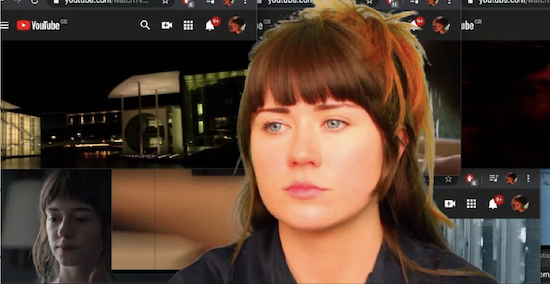

Henny Woods’ Echoes of Difficult Conversations During Lockdown offers another look at personal history, but through the use of voiceover, using YouTube clips to provide insight into the mind of the filmmaker as more than a creative figure. Woods sits in front of a green screen as YouTube videos that span genres play behind her, while a voiceover recounts strange and awkward conversations she’s had throughout her life, from interactions with a lover about his ex-girlfriend to family members asking about her future plans. While none of the footage is of her or her digital conversations, the amalgamation of footage reflects the subject of the conversation. In remembering an old friend, clips from Ghost World play as a relic of close friendships. Woods’ unique filmmaking method echoes the relationship many of us have with the Internet: scrolling mindlessly and remembering past mistakes triggered by old videos, oddly specific tweets and Reddit threads. Woods invites the viewer into her mind, granting permission to listen to just a few minutes of her private thoughts and creating a brief yet strong bond with the audience. Woods wants to share intimacy in whatever way she can, in a time where it feels impossible.

While physical contact is all but lost in the face of a global pandemic, there is nothing we crave more than intimacy – those long late night confessions at an emptying bar or just the ability to sit next to a friend again. These films, then, offer a eulogy of sorts to traditional ideas of what interpersonal relationships are, and a look forward at what they have become. They have not gone away, but they might never be the same. Each of these short films becomes a way of processing grief over lost affection. They echo how much we crave to touch, hug, and love, and how we never knew how much we wanted that until it was taken away.