Gary Cooper was a quiet man and an American icon. The strong, silent type, across more than 80 leading roles he typified an ideal that even today remains the very model of American heroism. His most powerful performance, however, took place in Poland – and came not in a motion picture, but a still image.

Anna Walentynowicz was just five months from retirement when she was fired. She had worked at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk for 30 years, first as a welder and later as a crane operator. Now they wanted her gone.

Why? Walentynowicz was a fierce trade union activist and a thorn in the paw of her communist superiors. Management made their move on 7 August 1980. It did not go well.

Following Walentynowicz’s dismissal, about 3,000 workers downed tools. Worse still, they started to talk. From the resulting country-wide strikes sprang Solidarity, an anti-authoritarian social movement and the Eastern Bloc’s first officially recognised free trade union. Its goal? Democratic revolution.

Poland’s communist rulers, the Polish United Workers’ Party, wanted no such thing. They imposed martial law in 1981, forcing Solidarity underground. But the group kept growing. By the end of the decade, it was too big to ignore. Eventually, in April 1989, the government laid a trap: an election that would decide the fate of the country. The catch? Solidarity had only two months to prepare.

“That was a trick,” Jacek Kołtan, a philosopher and political scientist at the European Solidarity Centre in Gdańsk, tells The Quietus. “They were certain Solidarity wouldn’t be able to organise in such a short period of time, without any kind of infrastructure. They wouldn’t be prepared.” Surely this scrappy underground movement wouldn’t be able to raise a posse in time? Right?

Enter the sheriff.

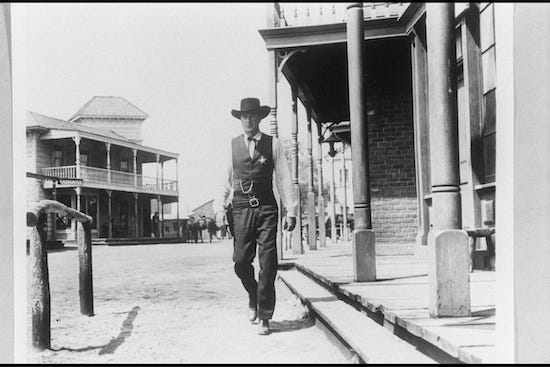

Directed by Fred Zinnemann, High Noon is one of the great Westerns – lean, raw and terrifically taut. Gary Cooper plays Will Kane, outgoing marshal of Hadleyville, a once lawless town now enjoying a period of stability. But all that will go up for grabs once murderous outlaw Frank Miller arrives on the noon train. Until then, Kane has to raise a posse of his own. The film unfolds almost in real time, the clock ticking with deafening volume as Kane quietly scrambles to convince the locals to fight beside him. In the end, though, the marshal chooses to face the coming threat – physical, personal, existential – alone.

High Noon was released in the US in July 1952. It reached Poland in 1959. Westerns were enormously popular in Central and Eastern Europe at the time, and when they landed in the East, they needed local-language posters to match.

Polish artists were first commissioned to provide posters for US films in 1947. The results were unique: subversive, inventive, provocative, political, and with no parallel in the States. Western films in particular seemed to ignite a fire in the Poles, who fanned the flames to send smoke signals that the country’s communist censors didn’t know how to read.

“When the Western travelled beyond the Iron Curtain, clearly all bets were off,” writes Kevin Mulroy in Western Amerykański: Polish Poster Art and the Western. “Ostensibly merely advertising a Western, the artist was able to include in the poster statements about America, Poland, individual experience and universal values.”

Polish artists identified in the Western themes of aggression and subjugation that reflected their country’s past and even their personal experiences, says Mulroy. In creating Western posters, they were able to express not just their views on American imperialism and Polish colonial experience, but their “universal abhorrence of violence as a means of resolving conflict”.

High Noon was perfect for such treatment. Marian Stachurski designed the film’s original Polish poster, in 1959. Grzegorz Marszałek designed another, for its reissue in 1987. By the time the election rolled around two years later, its marshal was still on people’s minds.

“Obviously something in this one man’s act of courage and sense of honour appealed to the Polish people,” writes Frank Fox in Western Amerykański. “A population frightened and forced into submission identified with someone who overcame fear and fought against all odds.”

Tomasz Sarnecki understood this. Influenced by his country’s decorated history of poster design, shortly before the June 4 election of 1989, the 23-year-old design student put together a simple campaign poster. It featured Gary Cooper as Marshal Will Kane, wearing the Solidarity logo above his tin star. In place of his holster, the marshal holds a ballot paper in his right hand. The only words on the poster are the name of the film and date of the election. The message was clear: Poland’s own high noon was coming.

Photo: Renata Dabrowska / European Solidarity Centre

For director Zinnemann – a Jew born in Austria-Hungary, now Poland, who had fled fascist Europe in the 1920s – High Noon was about the fragility of democracy, and how little pressure is required before civilised people begin acting against the interests of themselves and their community. But such a neat summation betrays the film’s knotty political history.

High Noon was intended by writer Carl Foreman as an allegory of Hollywood in the grip of the McCarthyism, with Hadleyville a metaphor for a Tinseltown whose residents were crippled by civic complacency, afraid to speak out for fear of being blacklisted. John Wayne, for one, thought it was a disgrace. He called it “the most un-American” movie ever made.

Funny, then, that Dwight D Eisenhower, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton and George W Bush have all cited it as their favourite. High Noon is also viewed as anti-communism – a victory for American law and the story of an individual’s triumph over collectivism. The Soviet Union’s Communist Party newspaper Pravda attacked the film, calling it a “glorification of the individual”. But it was precisely this individualism that appealed to the people of Poland.

Wayne couldn’t have represented Solidarity – like Cooper, the Duke was a star-spangled Republican patriot, but he didn’t have Coop’s patience, his poise, his haunted beauty. Nor could Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift, Gregory Peck, or any of the other actors who turned down the role of the marshal before it was offered to the man from Montana. Coop was identified with a particular kind of American ideal, writes David Thomson in Great Stars: Gary Cooper: “the shy, noble man under pressure”. In 1989, with freedom on the line, it was Cooper and Will Kane who best represented Polish hopes.

Gary Cooper never thought of himself as a particularly good actor. He didn’t like to talk. He had a reputation for paring back his lines. To co-stars and set visitors alike, Cooper just didn’t seem to be doing anything. “But then the next day they saw the dailies,” writes Thomson, “and Cooper held the screen – his waiting face, his coiled body – there was nothing else to see. The magic had worked.”

This is the magic of the Solidarity poster. Coop could do more with the drop of a shoulder than many could with a monologue, and here Sarnecki harnesses the actor’s natural minimalism: a motion picture distilled into a still image. In disarming the marshal, too, not only does the poster represent the movement’s commitment to non-violent protest, it intensifies the terrible vulnerability of Cooper in High Noon.

The actor first broke into the top 10 at the US box office in 1936. Back then he was beautiful, elegant. By the time of High Noon’s release in 1952, he was an American icon – but he was also arthritic, worn, worried. He had less than a decade left.

“More than ever before,” writes Thomson, “in High Noon Cooper’s walk is guarded or cautious, and the pain on his face is never quite wiped away.”

Cooper’s performance is deeply compelling. Kane is rigid and unflinching in public, but naked and shrinking in private. Many western purists, like Wayne, thought it unspeakable that a hero should weep or show fear in the face of hardship. But from fear comes courage, and it’s this story of a man finding the will to act when others won’t that is High Noon’s enduring power.

Given the short time that Solidarity had to prepare for the June 4 election, Sarnecki’s poster also evokes the film’s dreadful sense of urgency. High Noon’s crippling ticking clock motif seems to compound Kane’s worries: something dangerous is coming.

On the eve of the election, the poster was visible all over Poland. “I come from a very small town, 20,000 people living there,” Kołtan says, “and I saw the posters as a young boy on the streets. It was the first time you got Solidarity logos and symbols in public spaces, and in such a massive way. People felt, ‘Even if we lose, it is a revolution.’”

Solidarity did not lose.

On June 4 1989, the outlawed trade union given only two months to prepare won by a landslide. This was the beginning of the end for communism in Poland. The following year, Solidarity leader Lech Wałęsa became the country’s first democratically elected president since 1926.

Years later, Polish newspaper Rzeczpospolita would declare that “Solidarity’s list of virtues had in it something of a Western”. It’s true. Poland’s history with the US stretches back to the Old West and further, and its fight for democratic revolution was lassoed in American ideals. In Sarnecki’s poster, that grand symbol of American freedom, myth and morality, the cowboy, was made a mascot. And as Marshal Will Kane, a paragon of popular American identity had helped deputise Polish citizens. Poland’s high noon had come.