I’m writing to you from the United States, the day before the presidential election––the one that will either hopefully be the first step to clean up the destruction of the last four years, or plunge the country deeper and deeper into fascism.

Most of us here are focusing all our energy into the possible outcomes of the election, volunteering and fully giving into the sleepless nights of compulsive timeline-refreshing. It’s not as if anyone needs another reminder of America’s deeply broken political situation, but two recent documentaries––Heidi Schreck’s What the Constitution Means to Me and Jesse Moss and Amanda McBaine’s Boys State––offer a sobering look at who is left behind in democracy’s wake, and more crucially the radical change that needs to happen to make the United States a equitable place to live.

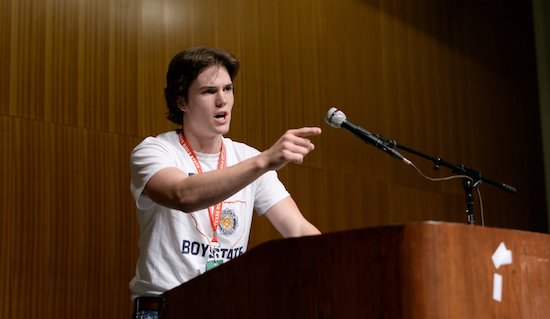

Boys State is a cinema-verite style look into 2018 convening of Texas’ Boys State, a national program set up by the American Legion in the late 1930s. In this convention-style summer camp, teenagers from across the state descend on Austin to set up a mock state government. The nearly 1200 boys are randomly split into two parties (the Federalists and Nationalists) and must come up with a party platform and run candidates for local office. If this seems like a real-life adaptation of Lord of the Flies, it’s because it is––but let’s not pretend that the House of Congress isn’t also frighteningly similar to William Golding’s cautionary tale. After promises of bipartisanship and holding themselves up to democracy’s ideals, the Federalists and Nationalists quickly turn into two militaristic factions, reduced to right-wing ideology, racist jokes, and toxic masculinity. There are no direct chants to MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN, but that still feels highly plausible amongst these young men––and part of the sick suspense of Boys State is seeing how much some of these teens are willing to borrow from Donald Trump’s (or Ben Shapiro’s or Ted Cruz’s or Stephen Miller’s) playbook.

Whereas Boys State offers a look into the minds of today’s youth, Heidi Schreck’s What the Constitution Means to Me sees Schreck looking back at her teenage years and realizing the way politics have altered the course of her and her family’s lives in ways she was not capable of understanding when she was young. When she was 15, Schreck competed in debate competitions to earn college scholarships. The prompt for these debates across her home state of Washington and the rural Northwest was simple, asking, “What does the Constitution mean to you?” Schreck and her competitors would give speeches about this document, cheerily reciting the ways the Constitution has changed their lives for the better. In this recording of Schreck’s Pulitzer- and Tony Award-nominated play, the present-day Shreck looks back to these speeches of her youth, now knowing––and experiencing––the ways America’s laws were set up to further marginalize and inflict violence on women and immigrants. She talks about her beloved grandmother, whose second marriage quickly turned violent and sexually abusive, leaving Schreck’s mother and aunt with no choice but to testify against their and their mother’s abuser in court with little to no justice. She learns of the lasting trauma of this situation when the Equal Rights Amendment, a long-gestating constitutional amendment that codifies equal protection under the law for all Americans regardless of gender, failed its congressional vote as a last chance effort at ratification in the early 1980s.

It’s terrifying to watch these films back to back and see the vast difference between these visions of what American can and should be. One one hand, What the Constitution Means to Me’s Schreck emotionally discusses how 1973’s Roe v. Wade allowed her to get a safe and legal abortion in college, and how that right is slowly being chipped away by misogynistic judges who believe that the Constitution does not outline a person’s right to make their own choices about their pregnancies. Cut to Boys State, where West Point hopeful Robert rails against abortion in his gubernatorial speech to a crowd of rabid boy – only to admit in an interview that he is actually pro-choice but thought that a strong anti-abortion stance would give him a better chance of being elected by the delegation. One of the only teens running for Boys State office that seems to have some sort of conscience (political or otherwise) is Steven Garza, who got into local politics after being inspired by Sen. Bernie Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign. The “conscience” of Steven does not come necessarily from his political views (although it is refreshing in this context to see someone not slide into Trumpism) but from the pride he has for his campaign and views, despite the fact that his support for gun control would eventually cost him votes in favor of his deeply conservative and pro-gun opponent, Eddy. The deep cynicism and ends-justify-the-means style of campaigning from the other teens is disheartening and begs the question: if the Boys State program is supposed to be a model of American government system, is the real-world equivalent of it just as rotten? And, could these teens be the next generation of government officials who willingly inflict trauma through legislation on families like Schreck’s and others across the nation?

In watching Boys State’s elections, I kept flashing back to the last 30 minutes of What the Constitution Means to Me in which Schreck invites an impressive and knowledgeable young debater to argue whether or not we should abolish the Constitution––understanding that American laws and the Constitution itself were only made to protect a small segment of the population and enforce strict codes on everyone else. With the vote of the audience, Schreck and the young woman decide that the only way forward is to make a new code of law that actually protects all Americans. I doubt that Moss and McBaine made Boys State as an argument for metaphorically burning it all down and starting over––the focus on Steven and the few moments of supposedly bipartisan reconciliation seem to suggest a kinder view that this nation is momentarily broken, not fundamentally flawed––but it’s hard to see it as anything but that, in consideration of not only What the Constitution Means to Me but everything else that is going on around us: mass voter suppression, court-rigging, and rampant police violence against protestors. One of the stars of Boys State, René Otero, wrote an op-ed for The New York Times following the film’s late summer premiere. In the piece, he considers his experience at Boys State, saying: “I did emerge from Boys State more inclined to be civically engaged. But what it also taught me was that I want to stay away from politics. What I learned is that the electoral process makes people complacent. It is not intended to accommodate those of us who are Black, or brown, or queer. To effectively represent my identities and communities is to be labeled ‘radical’ and unelectable.” American politics are not broken––they are just working the way that they were designed hundreds of years ago.

“Patriotism” is a word that gets thrown around a lot, not just in Boys State and What the Constitution Means to Me but on both sides of the political aisle. In his aforementioned op-ed, Otero discusses what patriotism means to him: “Boys State immersed me in a culture that refuses to criticize America, confusing praise with patriotism while ignoring the fact that with love comes accountability. I believe that to love America is to be as cynical about our political system as necessary until real change is made, because faith in what worked in the past won’t get us through.” It’s not anti-American to acknowledge the way that our laws are set up to fail anyone who isn’t a rich white man, and it’s an act of love to overturn the systems that perpetuate these cycles of hurt and disadvantage. Both of these films make the path forward clear: the time for dismantling these systems is now.

Boys State is available to watch on Apple TV+ now