They all make movies. All of them. And most of those movies will barely be seen. The chumps, the freaks, the punks, the grrrls, the conmen and the madmen and the people who walk on their hands. They all pick up cameras and tell their stories and then they slip behind the makeshift screen, trailing late-nights in their wake. Intentions range from conniving to compassionate; courageous to criminal, and they leave something of themselves hidden in every shot.

Time goes by.

The American Genre Film Archive (AGFA) is a non-profit film distributor set up to scour the church sales, flea markets and crumbling theatres of the USA looking for buried movies to restore, preserve and introduce to audiences. Some of these films will be being seen for the first time in 50 years, many will never have been shown to an audience at all. Some will have been filmed on a VHS video recorder in a suburban backyard by kids high on illicit copies of Evil Dead 2 and the fumes from sun-baked corn syrup, while others are pained deliberations on alienation from brains on the edge of rebellion. Some are basically porn with monster masks. All are worthy of saving.

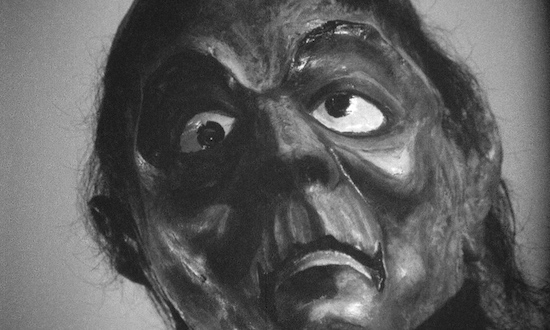

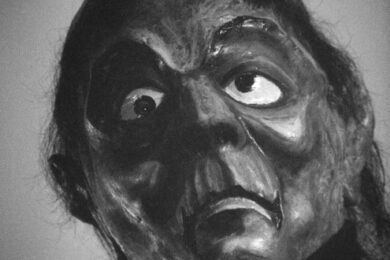

Movies like The Zodiac Killer, filmed and exhibited by the owner of a pizza chain in order to catch a mass murderer, or 1980’s Effects, a hangout-slash-fake-snuff movie that mostly consists of coked-up cast and crew members of George Romero’s Day Of The Dead smoking weed. Or Treasure Of The Ninja, William Lee’s open-hearted back garden martial arts epic. And then there’s Wicked World, Barry J. Gillis’s excruciatingly raw descent into VHS delirium.

Joe Ziemba is one of the founders of AGFA, and ahead of the UK Blu-ray release of two of their most essential discoveries – Wicked World and the Floridian trash nightmare, Sometimes Aunt Martha Does Dreadful Things – we talked coincidence, empathy, clarity and The Search.

The Quietus: Can you explain what AGFA is?

Joe Ziemba: AGFA is a non-profit film archive and distributor, the biggest non-profit film distributor in the world. We support our mission through theatrical screenings, video releases and freelance lab work. AGFA started as a film archive of 35-millimetre prints, and at this point we probably have around five or six thousand individual prints – features and trailers – in the archive. Our theatrical catalogue is up to about 1400 titles that we rep all over the world. We grew pretty rapidly, after we decided that we wanted to bring it to the next level and started getting the rights to the movies instead of just having the prints.

You also do the Bleeding Skull website with Annie Choi. How does that fit in?

Bleeding Skull is a sub-label of AGFA that we use for the shot-on-video movies. It’s something I started in 2004 as a site where I wanted to write about movies that I loved that weren’t getting the respect or the recognition that they deserved. That grew into a book and then another book (Bleeding Skull: a 1980s Trash Horror Odyssey and Bleeding Skull: a 1990s Trash Horror Odyssey), and a releasing label with Mondo. We did a partnership with Mondo for a few years – 2014 to 2017 – and then a year after that started releasing blu-rays with AGFA.

How do you go about sourcing the films?

It’s very intense and obsessive, I will say that! It’s a really fun process. It’s pretty much why I feel I was put on this Earth – to find movies and discover them and share them with people and make people happy through those discoveries. It’s something I obsess about constantly, in all of my free time.

I have so many different outlets, like AGFA and Bleeding Skull and programming movies and doing shows, so everything that I find falls into a different category – somehow I can use it and bring it to people. It’s a lifelong journey of research and obsessiveness and fun. My mum is also a librarian, so I think that’s where I got it from – organising and researching and finding things.

So, you have copies of old listings and set your sights on something? Say you see something called Castle Of The Screaming Dolls. What’s the first step in trying to find this mythical film? Where do you go?

It all depends on the source. I’ll read about it in an old alternative cinema magazine. There will be a classified ad in this magazine from 1996. Where did it go? What happened to it? And then from there it’s just getting into the research and doing the work to find this person. Sometimes it’s as easy as IMDb or Facebook or Twitter, but sometimes people aren’t online, and you have to go a little bit deeper and find out where they last lived and if they’re still alive. There are so many different strains. It’s a lot of detective work.

When you look at some of the films it’s clear that you’re dealing with some unique personalities, as well. People who’ve lived pretty interesting lives. Getting in touch with some of them must be a tall order.

Sometimes it can be extremely difficult, especially if they made one movie and there’s no record of them. If they’re not on social media and there’s no way to contact them, you’ve got to go down different routes. Sometimes it’ll be that one of us writes a review for Bleeding Skull of something super obscure and then we’ll get an email from the filmmaker two weeks later, “I can’t believe you’ve written about my film. No one’s ever done that, thank you!”. Then if it’s something that we’re interested in then we’ll start a conversation and go from there.

I always find there’s a lot of coincidence in these processes. As someone who buys a lot of records, I’ll think about something I’m after and the next day it’ll show up in a box right in front of me. Does that happen to you as well?

It totally happens! We’ve got to follow our gut on things like that. Brett at AGFA, head of theatrical, always says he’s a big believer in signs. If something is speaking to you and you’re seeing coincidences, then go do it. Make it happen.

What do the filmmakers generally think? Have you ever had a director say, “No, you can’t have anything to do with my film”?

The only time we’ve run into that is if it’s someone that wants a ridiculous amount of money for something that will never get its return on that amount. There are movies like that, where it’s like, “I’m in love with this movie and I really want to bring it to people,” but then the filmmaker is asking for this obscene amount and they won’t budge on it.

In general, one of the most fulfilling things that happens when you give these films a wider audience is the joy it brings the filmmakers. Having them tell us, “No one ever gave a chance to my movie back when it was released.” Now it’s got this whole new lease of life and they’re very appreciative and happy. It’s a great feeling. As a non-profit we’re not performing brain surgery or solving real problems for the world, but we do get to bring these tiny little capsules of joy to people and also to the filmmakers, just by giving love to their films and the work that they did.

That really comes through. You read the reviews on Bleeding Skull and the passion is very real. There’s no gatekeeping. It’s all about sharing. What’s the process when it comes to putting your money where your mouth is and releasing something?

It’s a case-by-case basis. It’s pretty much an open door at AGFA so anyone that’s part of the team can suggest a movie and then we’ll figure it out from there. It starts with that passion and then it’s what we think will resonate with the people who are buying the film. There are plenty of movies that I love with all my heart, but I know are not for audiences, so I’m not going to go after those movies because I realise it’s not going to be for everyone. You have to make sure it’s going to connect with people and it’s not something that’s so outrageous that we can’t sell it.

With the shot-on-video stuff, because it’s so comparatively cheap to produce, the visions become very personal. I imagine there is stuff you see that’s not only too obscure but also pretty nasty.

Oh yeah. That’s not something we ever really look for in movies. That kind of confrontational stuff isn’t something we seek out. If someone really wants to put out an X-rated Cannibal Holocaust shot-on-video rip-off, we’d be like, “Someone else can cover that.”

How do you go about releasing a film like Effects? Because you’re starting to deal with some bigger names as well, aren’t you?

I host a screening series here in Austin called Terror Tuesday every week. Back in 2015 or 2016, we had the print of Effects, and I really wanted to screen it and couldn’t find the rights holders anywhere. I had a feeling that it was [actor and composer] John Harrison and I knew he was around, but I didn’t know how to contact him. If we have a print that we want to play then we’ll do our due diligence and make sure that we try to find the people involved.

If we can’t, then we screen it and then hopefully they hear about it and we find them that way. It’s a little risky and sometimes it can be a bad thing. In this case about three weeks after I did the screening I got an email from John Harrison that said, “Hi, I’m the producer and star of Effects. I’m shocked because none of us have any film elements. Where did you get this print? How did this happen?” I was like, “Oh shit, I’m going to get in trouble”. So, I wrote him back and said, “I’m happy that you reached out and I’m happy to pay for the screening”. He was like, “Don’t worry about it”. He just wanted to know where the print came from and what it looked like, because they had no prints for the movie because it was so rare.

We got to talking and I said, “It’s an AGFA print, it’s the only print I know of in the world, and we have it here in the archives”. At that point we were just getting started with releasing movies. We were in production on Zodiac Killer which was our first release. I asked him ,“Would you be interested in releasing this on Blu-ray? Because we’d love to do it.” He got back to me within a day and was like, “Let’s do it”. We were blown away that we were able to work with them. They’re such great people and such a pleasure to work with.

So, you’ve got 1991’s Wicked World coming out, which knocked me on my ass when I saw it. How did it first come to your attention?

I was a big fan of Things from 1989, which is the first movie that [Wicked World director] Barry Gillis made with his creative partner at the time. It’s a canonical trash horror movie to me. Shot on super eight and edited on tape and so surreal – so distinctly Canadian – in the way it was set up. There’s nothing else like Things in the world. I found out he had made another movie called Wicked World. At the time, there was no way to see it, but Barry ended up self-releasing a DVD through Amazon, and I found it one day and ordered it and I was floored by the movie. When we first started to do the Bleeding Skull releases at AGFA I had Wicked World on the list. Barry was approachable, he’s on social media, so I just reached out to him and asked if he’d be interested, and it worked out.

It’s an incredibly personal vision. Watching it is like seeing the world through someone else’s eyes. But it’s a bleak vision, isn’t it? Was it intimidating approaching this guy?

Yeah, I would agree with that. You’re stranded in someone’s brain and you’re along with them for the ride. I knew from reading interviews with Barry that he was a functional person I could talk to. With acquisitions, though, I don’t really have any roadblocks. If the movie is completely nuts, I’ll still try to make it work out with the filmmaker. It might not work out if they’re being very difficult, there’s a number of ways it could go. But it’s always worth a shot. Everything is worth a shot, no matter what.

With the more outsider stuff the temptation can be to write the production off as cheap or slapdash, especially when it’s shot on video, but with Wicked World there’s a really deliberate, fastidious sensibility at work. Particularly the sound mix. There’s an obsessive attention to detail and texture.

Oh yeah, I think that’s what makes it so special. When it first came out, we got an email from a customer that said, “I think there’s something wrong with my Blu-ray because the sound is so weird. Sometimes it comes out of this speaker and sometimes it comes out of this one…”. Well that’s the way Barry mixed it! That aspect is so unique to that film and that filmmaker. No one else would mix a movie like that. It adds so much to the experience. It is very psychedelic. It’s like stepping into a portal of surrealism that doesn’t exist anywhere else.

When you’re dealing with these sorts of personalities, watching the films becomes an empathic experience. It’s about understanding somebody who you would never normally meet.

Absolutely, there’s so much of that involved. And that also goes back to releasing them and getting to work with the filmmakers. How much it impacts them and maybe even makes their lives a little better, knowing that their movie is accepted now.

I get the sense that the shot-on-video horror films are gaining a bit more attention now. Is that something you’ve noticed?

Absolutely. I think there’s way more acceptance of it. When I started Bleeding Skull 20 years ago, I didn’t even put my name on the reviews. I was worried that it would impact my job! At the time, people looked at you like you had lobsters crawling out of your ears if you were like, “I watched this shot-on-video horror movie”. People didn’t get it. But because of all the recent attention given to outsider movies and these films from beyond the fringes of society getting such beautiful releases, it has helped to get it out there. I think the community of people that enjoy these films has got more confident over the years in their love for these movies. That’s one thing that the internet has helped a lot with. There are many things about social media that are horrible, but one thing it has done is bring together like-minded people to celebrate these movies.

I also think the general quality of the images we consume on a day-to-day basis – streaming videos and so on – is quite low. I wonder if that might play a part in people being able to accept movies that are shot on non-professional equipment.

Yeah, I think so. It also has to do with people coming of age that appreciate the format. There’s definitely a nostalgia for it, so I think that’s a gateway. I still can’t watch movies on YouTube. I know there’s a lot of bootlegging, but it looks like shit. I cannot watch stuff that’s just all blocky and gross, the pixelation drives me crazy. But I think you’re right.

That lack of clarity also leads into the idea that it’s taking a more textural approach. There’s a sort of accidental avant-gardism at work.

Yeah, and I love that. That moment where trash horror meets the avant-garde, right in the middle. That’s such a great place to be and that’s where inadvertently most of the movies end up.

Everyone has a camera now and everyone can make films. Are there any trends that you’ve noticed among newer filmmakers?

There’s more personality coming through because access is there where it wasn’t before. People who are starting to make films now, there’s so many ways to go about what they do and there’s so much access to information that I think it lends a confidence to what they’re doing. People are bolder about what they want to put out there.

I’ve seen a lot of no-budget filmmakers picking up a camera, getting their friends together and making a movie because they have to, which is very similar to the way things were done in the ‘80s and ‘90s, but now with YouTube and social media people can make a movie on the weekend and then distribute it on their own. It’s really empowering. There are stories being told by people who maybe didn’t have an outlet and now they have that outlet, they have that creativity. That’s something that’s been really refreshing to me. There’s been a lot of new DIY no-budget stuff that I’ve been really enjoying in the past few years. Being online, being on Letterboxd and seeing all this great stuff happening, you can’t help but get excited about it.

For someone reading about AGFA for the first time, what have you released that you would recommend they check out to get a feel for what you guys are doing?

What Really Happened To Baby Jane And The Films Of The Gay Girls Riding Club is a really special release for us, because as a non-profit it’s really important to find those voices that normally do not have a light shined on them and to make sure that they’re given the attention they deserve. That release in particular was really important because it was such a big part of queer genre film history and it was virtually unknown.

The Films of Sarah Jacobsen was a really important release. I Was a Teenage Serial Killer (1993), her first short film, could be construed as horror in a way, but her main feature film Mary Jane Is Not a Virgin Anymore (1996) is very much a coming-of-age ‘90s slacker drama. We weren’t sure how that was going to be received after putting out Zodiac Killer and Soul Tangler and things like that. But it was so well received. It was just an outpouring of love; of people discovering her films for the first time. That was really cool.

Also, I really like some of the mixtape stuff that we do, because there’s not another label doing that. The AGFA Horror Trailer Show was a really important release for me personally because that was something we just conceived together and made happen. We struck a print and it played all over the country and then we decided to release it on Blu-ray just after that. Working on that together and doing the commentary as a team, there was a lot of positivity and energy around it. I always look upon it fondly.

Treasure Of The Ninja and The Curious Dr. Humpp are out on Blu-ray in the UK now from 101 films, with Wicked World and Sometimes Aunt Martha Does Dreadful Things following on the 15th of August