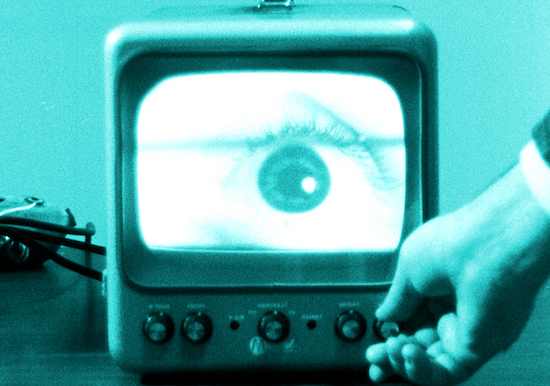

‘Adam Curtis CAN’T GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD: AN EMOTIONAL HISTORY OF THE MODERN WORLD (BBC iPlayer)’

Whenever faced with grumbling questions about the value of the BBC licence fee – why is Casualty still in a Saturday night slot after about 75 years, why is the news editorial often of questionable veracity or integrity? – to this writer, at least, the rebuttal is always: “Yeah but… Adam Curtis.”

At 65, having spent the best part of 40 years creating documentary films for the BBC, Adam Curtis has become a lauded yet still rather cult-like figure with a style and approach to storytelling that is entirely his own. He is easily the most intelligent and engaging documentary filmmaker working today, and his new series Can’t Get You Out of My Head: An Emotional History of the Modern World could be the finest work of his career.

Spanning eight hours over six episodes, the series presents an audacious and frequently mind-boggling attempt to explain how we got to the present moment: turbulent and chaotic times in which nothing ever fundamentally seems to change, during which those in power have lost the ability either to make sense of it or offer a way out to something better. It is an exploration of how, throughout history, different characters from all over the world have sought to break through the stasis and corruption of their time and transform reality – and how very often in so doing, have unleashed powerful forces that would ultimately lead to their destruction.

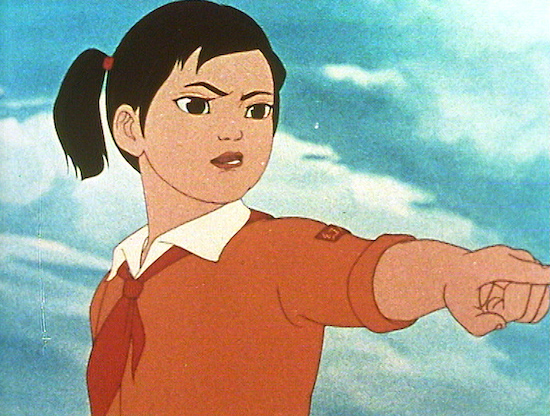

Adam Curtis being Adam Curtis, the films are awash with an extraordinary collage of sounds and musical set-pieces: the Mekons over a slideshow of conspiracy targets; the Sex Pistols’ ‘Who Killed Bambi?’ over the Red Guards wreaking havoc across China; Headless Heroes’ poignant version of ‘True Love Will Find You in the End’; The Specials’ ‘Do Nothing’; Schneider TM’s glitchy reworking of ‘There is a Light That Never Goes Out’.

As is also characteristic of Curtis, multiple narrative plates are kept masterfully spinning in the air throughout, criss-crossing and interlinking in fascinating ways: the two friends behind the Discordianism movement who set out to demonstrate the insanity of conspiracies; Jiang Qing, whose frustrated acting ambitions would see her unleash furious anger through her husband Mao’s Cultural Revolution; Daniel Kahneman trying to understand the human brain; Michael X raging against ‘Englishism’ in 1960s Notting Hill; Afeni Shakur (Tupac’s mother) running away from home to join the Black Panthers; the opioid epidemic, MK:Ultra, Project Iceworm, the Soviet collapse, the Mau Mau uprising, Booleian logic, complexity theory, artificial intelligence, the JFK assassination, and so much more.

Even by Curtis’ standards, the pace of ideas is close to overwhelming at times, but still feels like genuinely essential viewing to grapple with the maelstrom of the present and attain something close to a clearer line of visibility through.

I spoke with Curtis about the new series, the failure of any alternative vision to come to the fore, his unique filmmaking style, his relationship with music, and more.

The Quietus: The broad hypothesis of the series is one that you explored through the prism of Afghanistan in ‘Bitter Lake’ and the Soviet Union in ‘HyperNormalisation’. What drew you to the concept of widening the scope out further?

Adam Curtis: I became quite shocked by how extraordinary the disconnect had become. Although there was great hysteria over Brexit and Donald Trump, if you pulled back and looked at what was really happening over the past four years, nothing changed in terms of the structure of power.

The films attempt to look at all the different things from starting about 70 years ago onwards, that at that time seemed to be completely separate. On the one hand, you had a growing melancholy in this country about the loss of the Empire and an emergent anger among the white working class. On the other, labs in America were beginning to develop AI, and money was beginning to rise as a powerful force that would replace the old ideologies of the past. I wanted to trace how like little rivers these things were flowing towards the uncertainty of now, and how they joined up in really strange ways, often through the actions and emotions of particular characters.

In the last film, I say why I think we are in this state of stasis and offer three options of where we could choose to go in the future. I don’t tell you what the choice should be, but as a journalist I can point out the directions in which we might be going.

‘Adam Curtis CAN’T GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD: AN EMOTIONAL HISTORY OF THE MODERN WORLD (BBC iPlayer)’

The series opens with a quote from the late David Graeber, but I wonder whether you also took inspiration from Mark Fisher, particularly his argument that at the libidinal level there may not actually be that much desire for a move beyond capitalism?

I knew Mark, he reached out to me when he started writing about how culture is haunting us as he had realised that I’d been writing about that too on my blog. And you are right, both Mark and I shared that suspicion.

One of the things the left has yet to face up to is that if it really wanted to change things, they would have to give up a lot of their own privileges as individuals in the interests of actually helping a lot of people outside the system who are living anxious and uncertain times. In the second film, I tell the story of Michael X, who was a gangster but became a heroic figure for the left in the mid-1960s. But when he came out of prison, he found that all his white supporters had suddenly gone into a kind of commercial lifestyle hippie-dom. I was interested in him as a character because, although he was a nasty and violent man, he had a wry understanding of English white radicalism, that quite a few of the people who dressed as radicals and danced to Black music were still the children of the people who had run the Empire. And might still be wanting to run things.

In the third film you tackle climate change, which you haven’t done to the same extent in your previous work…

I began to notice that since the 1990s the climate change movement had become possessed by a very narrow technocratic solution, focused on just holding the planet’s temperature stable, and I thought this was ignoring power. I wanted to show how coal has a really complex history, it was obviously a key agent of climate change, but was also one of the routes of collective power of the working class, out of which came socialism and all the ideas that you can actually confront and take on privileged power.

I’ve often thought that a lot of the technocratic solutions offered to people on things like climate change try to abstract themselves from the past – it’s a modernist approach to politics. A lot of people in the climate change movement are now realising that – Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and the Green New Deal are saying the same thing – they need to link it to changing structural power in society now, and I think that’s absolutely right.

You argue that no one is offering alternative visions of the future. Could you argue that in recent years we have seen relatively different visions come very close to power – Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour and Bernie Sanders; both with flaws but at least willing to explore new ideas like Universal Basic Income and the Green New Deal?

But they still failed. You’ve got to accept the fact that you’re not giving people a powerful enough idea of an alternative future, one that will attract people who voted for Trump and Brexit, who you need on your side. If you look at what Sanders was saying in the 2016 campaign, it was almost word-for-word what Trump was saying – why have they shipped factories off to China, why are people living in derelict places addicted to opioids, why are we killing thousands of people in foreign wars, why is there so much corrupt lobbying? I still think he might have won in that moment, it’s terrible that the Democrats stitched him up. Remember that many of the people who voted for Trump in 2016 were the same people who voted for Obama, and unless the left really comes up with something bigger that can grab those people imaginatively then some really nasty people, much nastier than Trump, will.

One of the characters that appears in the series is Dominic Cummings. Despite his downfall, his story as a public figure feels incomplete. Do you think you’ll be covering him again in the years to come?

I had time for Cummings because compared to other politicians he actually had some ideas, even if they were completely bonkers. In the last film, I deal with the rise of complexity theory in the early-90s. It has become one of the great mythologies of our time, that through data you can know more about reality than humans do. Fundamentally this is flawed, because it accepts the system as it is, it never asks the question: who designed the system and in whose interest is that system designed? Cummings sensed the anger of places like the North-East, but because he’s a technocrat he didn’t see that by raising that anger it would also give rise to ghosts from the past, from a time when the Empire was falling apart and a magical nostalgic vision of England was invented, that was reaffirmed with the Second World War and later came up through Nigel Farage. So, he was doomed to fail.

‘Adam Curtis CAN’T GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD: AN EMOTIONAL HISTORY OF THE MODERN WORLD (BBC iPlayer)’

You’ve developed such a distinctive visual style, already fully-formed with Pandora’s Box and The Living Dead in the early ‘90s. Did you always have a clear idea stylistically of what you wanted to achieve, or was it more a case of trial-and-error?

It was pure instinct. I was doing what a lot of people were doing in music in the early ’90s – sampling and reworking the past. Out of that did come an aesthetic, but to be honest I never thought it out. Often it came about because I wanted to tell stories about quite abstract things. For example, in Pandora’s Box I wanted to make a sort of funny film about economics. I was just starting out in TV and was almost in tears when editing because I could find nothing to illustrate it and I thought I was going to be sacked. Out of that desperation I started raiding the BBC archive, I remember I even had talking squirrels in it at one point. Stylistically, a lot was born out of that necessity to get things done to a deadline.

Some critics of your work – for example, The Loving Trap parody – argue that what you do is very skilfully create elaborate narratives which make connections and draw parallels that are then presented as objective truth. Do you sometimes worry about being dismissed as part of the ‘conspiracy’ problem?

That parody is very funny and clever, and it made me reflect on myself, which is good. But let’s be clear, I’ve never in any of my films put forward a conspiracy theory. Over the last 20 years, when the mainstream left and right in this country have essentially fused together, out of that has emerged a very strong consensus. In the face of that, the term ‘conspiracy theory’ has transformed itself into a shorthand to describe anyone who challenges that mainstream narrative. My job, which the BBC has tasked me to do, is to provoke people and ask them, “Have you thought about looking at the world this way?” To pull back a bit and look at what is happening in a different way. But that is not a conspiracy theory.

You feature your staple artists in these films – Nine Inch Nails, Aphex Twin – along with a wealth of obscure and interesting others. Are you a music magpie always searching for strange new sounds to use in your films?

No, I just like music, it’s as simple as that. I have in my head lots of music, I’m very picky, but there’s lots that I’m inspired by, usually things that have a kind of modern romanticism. Nine Inch Nails is a very good example, he somehow manages to take noise and make it emotional, as does Burial. They capture that modern mood, somehow raw and machine-like but suffused with deep feelings and melancholy. When I’m editing and I know I’m starting to create a mood, bits of music will pop into my head and I’ll try them out.

There’s a wonderful piece of dark ambient music that you use a lot in these films and also in HyperNormalisation, but I can’t track it down…

I know what you’re referring to. Ever since I started working with Massive Attack we’ve done little bits of music to stitch together between the songs in the shows that we did. It’s very much a collaborative process between me and Robert del Naja, and increasingly I’ve used those in my films. What I’ve discovered is that Massive Attack, as well as being a wonderful band, are also a great covers band, so I can ask them to do a bit of music that sounds like John Carpenter mixed with, for example, the Dead Kennedys! I’ve got a whole load of files from them that I use quite a lot.

And you also use layers of found sound that you record yourself?

Yes, just bits and bobs. There’ll be a strange noise at the end of some news footage and I’ll sometimes play with it acoustically as a kind of sound collage.

‘Adam Curtis CAN’T GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD: AN EMOTIONAL HISTORY OF THE MODERN WORLD (BBC iPlayer)’

What this series showcases, as with your previous work, is your really eclectic taste in music. What’s the best gig you’ve ever been to?

It depends what you mean by best. Lying flat on my back on a pub table listening to Shane from The Pogues hit himself over a head with a tin tray as he sang was an extraordinary experience. But then gazing at Kanye West and Jay-Z perched on top of giant illuminated cubes at the O2 was musically a great experience – but also very strange, because it sort of symbolised what was happening to culture as the new technology rose up to embrace individualism and self-expression.

Two things were raised recently as sure contenders for a future Adam Curtis film. Firstly, the footage of the woman live-streaming her workout in Myanmar as the military coup rolled in behind…

People were saying the coup was a viral marketing campaign on my part. I got sent masses of those videos. Of course, I might have done one of them anonymously…!

Secondly, the Gamestop story. Do you think that perhaps represented the ghosts of the internet’s past, as an anarchic and democratising power re-emerging to take on the elites?

Initially I thought that, but it got more complicated. The Robinhood app portrayed itself as democratising the stock market, but I read that they got their real profits from selling on the data of the people who were doing the trading, just like social media when that was supposed to be a new democracy. And then all sorts of conspiracy theories started cropping up, saying that maybe the traders were actually the puppets of another set of hedge funds trying to destroy that hedge fund. And then the lefties piled in saying, “No it’s not revolutionary because they are trading in and reinforcing capitalism.” At which point I thought, this is typical of our time – what starts off as revolutionary has, within about three days, become a doom-laden mess of people eating each other, all unsure what the fuck it was about.

Why did you stop your BBC blog? Will you ever return to the written medium, with a book perhaps?

It’s quite exhausting and requires a kind of self-consciousness that gets a bit boring after a while, and I don’t want to be on social media. If you analyse my work, you’ll see I’m a very functional writer, there’s nothing fancy about my scripts at all, but I counterpoint what is quite a baroque and wild visual sense with a calm voice anchoring it. Every now and then I get publishers asking me about a book, but I don’t see the point, without the visuals and music I’d be throwing away 75% of what I’m good at.

When you complete a project of this scale, do you kick back for a while or are you always searching out new stories? Have you got your next project in mind already?

I don’t have a next project, but I come out of a journalistic tradition, so I just go and research stories. I have in the back of my mind that the things a lot of people are obsessed with at the moment, the magic of modern technology, may be seen quite soon as rather banal and mundane and a sort of con. I’ve noticed there are people within the advertising world beginning to question whether the idea that Google can actually target people as precisely as they claim might in itself be a bit of a con. Maybe it’s time to realise there are other things out there. So, my brain is tending that way.

‘Can’t Get You Out of My Head’ is now available on BBC iPlayer

Michael J. Brooks is a co-host of Creaky Chair Film Podcast which launches this month