It would be easy if one were John Milius to feel somewhat overlooked as a filmmaker and screenwriter. He has certainly spent his career in the shadow of friends and colleagues such as George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese, to name but a few. Milius was one of the driving forces behind Apocalypse Now, an uncredited script writer on Jaws, and many years later would be used by Steven Spielberg again to add some steel to the Saving Private Ryan screenplay. He was also co-creator of the epic HBO/BBC TV series Rome. An aspiring but failed soldier (rejected by the US Marines on medical grounds), an obsession with all things military has characterised Milius’s work throughout his career. A recent foray into video games recycled his 1984 movie Red Dawn, a cult favourite in which a group of high school children discover the true meaning of the American burden of freedom by machine gunning scores of Russian soldiers after an extremely unlikely invasion of the USA. Red Dawn is also the first truly great illustration of how simplistic and almost childlike Milius’s world view was at the time, and why he is probably more suited to portraying fantasy realms such as Hyboria.

The man himself seems to have few qualms about bowing to political realities, however, and his output reflects his obsessions quite clearly – as does his early involvement in the establishment of the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC), in which mega-ripped sweaty dudes pummel and choke the living crap out of each other for the pleasure of a baying crowd. In fact, it could be argued that he has made a comfortable career ruminating over the nature of Man: The Warrior, and could even be accused of essentially remaking the same handful of films over and over again.

Milius was the first director to take on the monumental task of adapting Robert E Howard’s famous Conan character for the screen. As is generally the case for such adaptations, he and co-writer Oliver Stone chose to jettison the bulk of Howard’s own, relatively meagre background for the character in favour of making him a physically and emotionally dislocated seeker of redemption. In Conan The Barbarian (named for the Marvel comic series; there never was a Robert E Howard story of that name) the bewigged man-mountain Arnold Schwarzenegger battles giant serpents, wild dogs, saucy witches and innocent camels in his quest to avenge the deaths of his family at the hands of villain Thulsa Doom, a charismatic tyrant worshipped by hordes of disenfranchised lost souls. By the end he’s hacked Doom’s head off and displayed it to the dismayed followers, who melt away, the hypnotic hold over them broken by this simple but visceral act of violence. To anyone who has seen Apocalypse Now this all feels vaguely familiar. Granted, Martin Sheen’s Captain Willard was not in the habit of punching out beasts of burden, but the Joseph Conrad Heart Of Darkness theme is the essential core of both films.

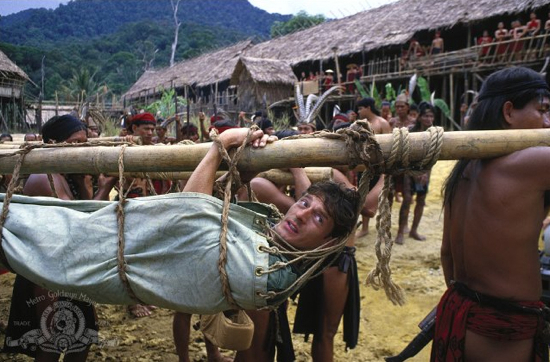

Milius took the opportunity to examine the ‘man up the river’ in more detail in 1988 when he wrote and directed Farewell To The King, the tale of a British officer, Captain Fairbourne (Nigel Havers), sent in early 1945 to organise resistance among the tribes of Borneo to the occupying Japanese army. To his surprise, Fairbourne finds American deserter Learoyd (Nick Nolte) living as king of one of the tribes. Here the movie departs from formula and becomes an intimate examination of that ‘man up the river’, how he established his holding and how conflict will force him to choose between personal paradise and duty, and to learn one of Milius’s favourite themes: the cost of freedom.

Farewell To The King highlights both the strengths and weaknesses of Milius as a writer and a director. Early scenes establishing Learoyd’s loving relationship with the tribe feel ham-fisted, clumsy and unconvincing. A montage sequence in which the tribesmen are trained in the use of modern weaponry is frivolous and curiously upbeat, but quickly becomes tinged with tension and danger on the realisation that simple intra-tribal conflicts could easily escalate into bloody civil war at the pull of a trigger. The resolution, instigated by the Captain in ruthless fashion but punctuated by a display of humanity by the King, ultimately wastes the build of tension by climaxing flatly and failing to capitalise on the raw emotions of the principal characters, and vicariously the audience, as they balance the life of a baby on a knife’s edge. None of this is helped by the fact that Nolte’s stylist appeared to be channelling Bonnie Tyler.

After returning to HQ due to malaria, Fairbourne experiences some cold shouldering and accusations of having gone native from his superiors. Fortunately he has the chance to hook up with his English rose love interest, a girl with the most bizarre British accent since Robert Duvall’s take on Dr Watson in The Seven-Per-Cent Solution. What follows, as the US command cynically placates the King’s requests for sovereignty with meaningless paperwork, may as well have been lifted wholesale from the exchanges between TE Lawrence and General Allenby in Lawrence Of Arabia. The whole passage is hackneyed and functional, with Milius even wheeling out the obligatory Fox brother (James) to play a stiff British colonel. Back in Borneo and buoyed up by his piece of paper, Learoyd cheerfully leads his tribe into war against the beleaguered Japanese.

In his previous films, Red Dawn particularly, Milius portrayed combat as brutal and cold. Yet here, in the first montage of the tribesmen sweeping the Japanese before them, the uplifting and whimsical score by Basil Poledouris sounds more suited to the mock pirate battle in Swallows And Amazons. It’s an odd stylistic choice that is only complicated by some rather curious demonization of the Japanese soldiers, leading to a subsequent violent battle scene that allows for the score to turn more sinister and doom-laden. Sadly this set piece feels poorly staged and hurriedly shot, so consequently lacks impact. By contrast the film’s observation of the aftermath of a one-sided slaughter in a village is deeply affecting and Nolte’s performance, mirroring the film’s opening when he witnesses the execution of his comrades, is heartbreaking. Even his "Nooooooaaaaaargh!" sounds suitably strangled and convincing, and should be the model for all future actors asked to do the dirty by their director.

Farewell To The King is an intriguing story that is simply told. The overriding impression is that Milius’s obsession is not focused exclusively upon the trappings of war, but the impulse within people that makes them capable of extraordinary, even terrible things. Thulsa Doom and Apocalypse Now‘s Colonel Kurtz were distant, powerful and enigmatic. Here, Nick Nolte builds upon the sense of internal conflict that was hinted at in Kurtz by having more time to establish a personality and by attempting to invest his performance with some complexity, rather than simply being brooding and mysterious. Nigel Havers deserves credit as he portrays his character with gravitas yet avoids coming across as stereotypical, despite some questionable dialogue. Thanks to the actors both characters effectively describe convincing arcs over the course of the story.

Unfortunately, the film itself lacks any great complexity and falls into the perennial trap of reinforcing that war is only hell when we and our loved ones are getting killed. It would be tempting to think that with a more skilled director Farewell To The King could have been a more successful drama, but in the hands of a modern studio it may well have just ended up being more mawkish and forced à la Spielberg or, worse, violent and cynical like Rambo IV. In its favour, and to the credit of Milius, it has a degree of integrity that is missing in most modern American cinema and, despite its shortcomings, provides a different eye on a number of well-worn themes. Ultimately, the film just manages to be less than the sum of its parts.

The widescreen DVD edition of Farewell To The King is released today by Second Sight Films.