If you’re not in the habit of watching Shakespeare, seeing one of his plays is liable to trigger frequent jolts of recognition. Phrase after phrase you’d unwittingly accepted as belonging to the common stock of English language will jump out at you, reminding you who invented it. Similarly, so intertwined with our notion of American modernity is the work of designers Charles and Ray Eames that the inexpert eye often doesn’t identify its origin. As the images zip by in Eames: The Architect And The Painter, again and again one thinks: "So that was theirs – and that – and that…"

Our view may lately have been skewed by Mad Men, with its East Coast vision of postwar, pre-counterculture cool, but among the details that programme so lovingly depicts is how an Old World, Eurocentric style lingered in the New York of the early Sixties. Don Draper frequents bars and restaurants full of shadows, plush and Tiffany lamps. What he sells, by contrast, and the people to whom he sells it – those belong to a nation falling in thrall to the new West, and to the light, clean, form-follows-function idiom of the Eames. Few can have done more than they to give the American Century its distinctly American look.

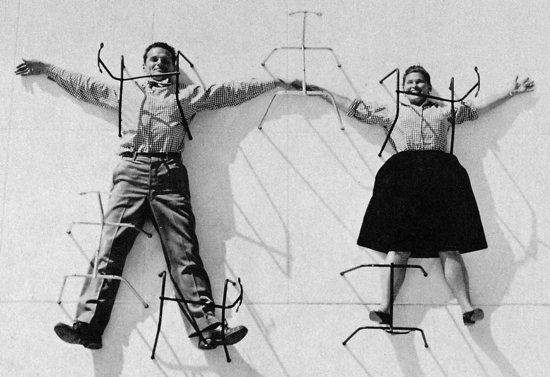

Charles and Ray were not, as was often supposed when their names were encountered in tandem, brothers. They were husband and wife; he was the architect, she the painter. Theirs was a union blessed with both symbolic resonance and fruitful serendipity. Charles Eames was born in St Louis, Missouri – that most archetypally Midwestern of cities, then emblematic of the sturdy virtues of industry and commerce – and raised amid blueprints and steelworks. Ray Kaiser’s birthplace is California’s capital, Sacramento. By her twenties, she was living in New York, where she became an abstract expressionist of note. Between them, they had America’s metropolitan cultural landscape covered. They married in Michigan, brought together by The Cranbrook Academy of Art. then decamped to Los Angeles to set up their Venice Beach design studio. It would prove a decisive moment – both a catalyst for and a premonition of the fusions (aesthetic, technological, architectural – eventually, musical and culinary) by which the relatively recently Americanised West Coast would in turn colonise so much of the rest of US. Admirers would say they not only revolutionised American style, but reinvigorated Modernism itself. It’s a fair claim.

The moulded plywood Eames lounge chair was the object upon which rested both their early reputation and countless of their countryfolk’s then less ample buttocks. It signifies the functional aspect of American Modern in much the way Marcel Breuer’s tubular steel and leather Wassily armchair does the European. Mass produced by the Herman Miller company of Michigan – which bought up Eames furniture as fast as they could design it – it is the defining object of a Fifties middle-class middle America, upwardly mobile in income and tastes. No less iconic (although inevitably not so broadly influential) is the residence they made for themselves. Part Frank Lloyd Wright, part Piet Mondrian, part construction kit and all serene, cheerful grace, the Eames House is, again, the transatlantic peer of a Bauhaus classic – Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion – with the additional merit that it was a real, working home, not an exhibit.

The Eames studio was prolific, not least because it employed a shifting host of uncredited young designers, upon whose selected insight and hindsight this documentary sensibly relies. Eames… whizzes breathlessly past one achievement after another, right from its artful computer-generated introductory sequence – as much a tribute to the ingenuity of (one guesses) Apple as of its subject. Which seems apt, given the parallels one might draw between the operation of the two outfits; the computer company’s debt to the clear and bright visual idiom of the designers; and the assertion that the Eames’ dense later work prefigured the Internet age. (It isn’t mentioned, but the open, busy, unstructured office life of ‘The Eamery’ – in essence, a productive playground – could have been a template for the later likes of Google.)

There is doubtless a conscious emulation of the ‘information overload’ approach Charles Eames brought to the studio’s own film work for government and corporate sponsors. If directors/producers Jason Cohn and Bill Jersey felt it would be a missed opportunity not to attempt the film a contemporary Eames studio might have made, who can blame them. It’s a shame they didn’t have more elbow room. As a concise single piece, this is instructive and easy on the eye; as a multi-part television series, it might have been richly illuminating.

When Eames… slows down, it does so to appraise the couple as characters, and to examine their relationship. Here, surprises are few and mild. It turns out that, like almost all people who do interesting and complex things, they were interesting and complex people. Charles was voluble, charismatic, sometimes brilliantly lucid, sometimes incomprehensible. Ray was reserved, intense, resilient, inscrutable to outsiders. They were imperfect, as is everybody. Their marriage was sorely tested, as are most. They built the happiest of dream homes, and found within it the heartache to match. There are no shocking revelations, and the twist now obligatory in the documentary genre is more of a gentle curveball. The film is none the worse for that. The Eames are fascinating because what they did is fascinating. Their ordinariness – in the sense that they are revealed, as private individuals, to have possessed ordinary virtues and ordinary flaws – is refreshing.

The narrative touches upon the sexual politics of a pre-feminist collaborative marriage, and shows how Ray’s contribution to the creative partnership was not only undervalued, but misunderstood. Charles had a genius for form. Ray too had a grasp of it, but moreover, she – as he did not – understood colour, a vital component in their work. The documentary deals nicely with contemporary context, hinting at rather than spelling out how the Eames studio’s arc tracked that of the USA itself, from post-war boom to Seventies malaise, when its final major work – the sprawling, cluttered, multi-layered Bicentennial exhibition The World of Franklin and Jefferson – was greeted with bafflement and rare critical disapproval.

What Eames… doesn’t go into – can’t, perhaps, risk without calling into question its own premise – is how little purchase the ideals on which the pair based their work, and which propelled so much else of what was admirable and productive in American thought and society of that era, hold on everyday America today. We are whisked along on a well-appointed tour, showcasing model lives of Brahmin artistry duly cherished by artistic-minded Brahmins – now the only demographic both likely to choose living in the Eames mode and able to afford it.

‘The Best for the Most for the Least’ was the motto Charles and Ray Eames applied to the furniture – painstakingly devised, robustly constructed, affordably priced, ubiquitously bought – which dominated the burgeoning suburbs and made their company’s fortune. Charles was the apostle of a nobler capitalism, of a rising tide which would not only lift all boats, but rig them out with airy elegance. His propaganda work (to categorise it thus is not to diminish its value as art) for the US government was undertaken in a genuine spirit of belief in the American way. The middle classes, those American dreamers upon whose growing custom the Eames studio was established, are foundering, pressed back into the wage slavery or precarious underemployment from which they lifted themselves. The capitalism Eames envisioned was supplanted by one whose rising tide drowns all but those on the decks of superyachts.

Charles and Ray Eames saw a new world coming, in which they would help redefine what constituted gracious living, and who might partake in it. It came, and now it’s receding, having outlived its prophets by fewer years than it lasted in their lifetimes. This film of their lives, assembled in their manner with the adept use of technologies far beyond their reckoning, is as lively, brisk, curious and likeable as they were. In their era, the lifestyle they sold was a viable aspiration. In ours, to which Eames… belongs, that lifestyle will be at best, for the most with the least, a beautiful fantasy, preserved in museums, on screens, or in a compressed, virtual form via the devices that are its foremost legacy.

Eames: The Architect And The Painter opens in selected cinemas nationwide this Friday August 3, with a preview at BFI Southbank on Wednesday. A DVD release will follow in September courtesy of Soda Pictures.