Sat between a middle-aged man in a sweater vest and Tom Rowland’s elderly mother, I resign myself to watching as the front row and stage left section of the BFI theatre begin frenetically raving. Strobes pulsate, a euphoric face briefly appears, a finger presses a button marked ‘HBHG’ before a sea of people go ballistic – both onscreen and off.

I’ve always thought a proper concert film would be the product of a kind of Quatermass experiment, but with an alternate ending. It should start with an audience member, a singular perspective, absorbing the most satisfying aspects of his environment until he swells up into the all-seeing, all-knowing and all-tripping Super Punter. His experience would encompass what was intended by himself and by the many creators of the spectacle before him. In other words, his would be the only trip worth committing to a mass screening. Certainly, most directors might set out with this in mind, but the unfortunate truth is that they usually end up with Quatermass’ grotesque, bloated and slime-slicked monstrosity, ultimately cornered by the media and set ablaze to prevent it spawning further self-indulging eyesores.

A reason why so many concert films are unsuccessful is because you could possibly have 50,000 revelers having 50,000 individual experiences at the gig in question, but the potential millions of people who may see it after that, they will have only one – and who is the filmmaker to pick which? Who should really have the free rein to decide exactly what the average careening, gurning, waffling concertgoer should get out of their night?

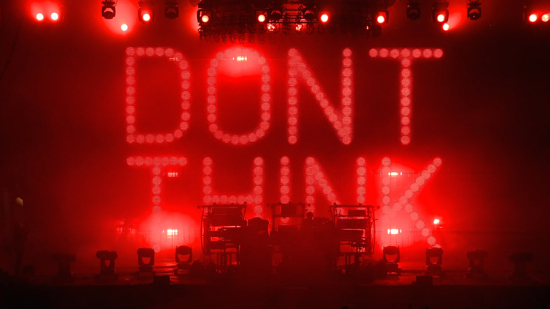

Well, considering that the director of Don’t Think, Adam Smith, has been at the helm of The Chemical Brothers’ notorious live visuals for 18 years and that the duo themselves mixed the audio, there couldn’t be a more informed opinion of how the show should be run. In fact, it’s practically a home movie. And if the outbursts of joyful gesticulation I spied at last Friday’s screening are any indication, their qualifications make the grade.

"I guess it works because we know that show so well," says Smith. "Marcus Lyall – who I created the visuals with and who produced the film – and I know every little bit of that music because we spent three months programming visuals and lights for it. We know the strongest visuals and the best bits where crowd are reacting."

Filmed during The Chemical Brother’s headline slot at the 2011 Fuji Rock Festival in Japan, Don’t Think stars a Japanese audience that’s very different from the one seen in most Western concert films. Some of the most critically praised examples, such as The Band’s The Last Waltz or Talking Heads’ Stop Making Sense (directed by Martin Scorsese and Jonathan Demme respectively), don’t dare veer from their subject matter and treat concertgoers as a necessary annoyance in the live process. At the other end of the spectrum are the super-immersive, fan-made movies compiled by blammoed kids in need of weed money, which show the gig entirely from the most beer-drenched and animalistic depths of the crowd. The All Tomorrow’s Parties picture and Beastie Boys’ (aptly titled) Awesome; I Fuckin’ Shot That! may imbue a cinema audience a with sense of nearness to the event, but still fall short of crossing the threshold between documented personal journeys and truly immersive experiences.

The trick to Don’t Think is that it doesn’t rely on the camera angles, physical perspectives or ultra-real points of view, but rather lodges itself firmly in the mind’s eye of the Super Punter. Despite the title, this film’s success has a lot to do with the way it thinks. At a gig there are times where the screens fill your brain’s field of vision, others when you are squinting through the crowds to lay a naked eye upon the central figures. You might be temporarily blinded as a throbbing strobe sends a blood rush to your head, or you might just find yourself staring with bemusement at the guy next to you who has just had some manner of religious episode over the opening thuds of Block Rockin’ Beats.

"If you’re at a gig you’re generally not just reverentially staring at the band," agrees Smith, "you’re looking around. There might be a pretty girl next to you or a nice looking chap. There might be someone really funny who’s just losing it. I think the concert experience includes all of that as well. We also really tried to merge the visuals with the concert itself. There are bits where we just layered visuals on top of the crowd so you feel like you’re immersed in them, which is something I think that you feel during a Chemical Brothers show – you know, you feel as if the visuals are everywhere."

Smith’s visuals stay with you, as they do with our Super Punter who ventures off momentarily to experience the Fuji Rock festival via a female fan. Glances of projected clowns, robots and twitching beetles interrupt the excursion, as the images remain fresh in our minds. One criticism would be that these jaunts around the event are a bit jolting, though it’s reasonable to suspect that they do break up the onslaught enough to prevent a potential deep vein thrombosis-like lapse in your neocortex. That’s not to say you come away unscathed: the whole experience subsequently leaves you with mix of rapture and satisfaction, but likely sporting a knitting needle-sized migraine and wheezing ventricles. (Though, as any seasoned chemical boy or girl knows, the comedown rarely keeps you from rushing back, gnarled notes in fist, to catch another hit.)

At once individually discombobulated and in synch en masse, the Fuji Rock community play an integral part in the reality-feel as they give the filmmakers an unbelievably – almost suspiciously – candid view of their experiences. Several faces make repeated appearances (I could easily sketch one man’s dental profile for the amount of times he flashed onscreen, mouth agape) though generally for good, emotive reasons. A particularly memorable moment comes during a segue out of Superflash when cherub clowns arrive in choral fashion before making way for a terrifying disembodied Pierrot face – who is in fact Smith’s father – quoting computerized Freddy Kruger: "You are all my children now". The camera focuses on a woman in the crowd whose utter paralyzing horror and awe is so genuine that you feel you may lose it too. In other scenes, blissed-out faces with uvulas exposed and eyes rolled skywards sway to the break beats, seemingly oblivious to the cameras being rammed nearly up their nostrils.

"We didn’t know that the Japanese audience would be so receptive," says Smith. "Some of those moments make you feel almost as though you’re intruding, like you’re in a documentary and filming a too-intimate situation. I didn’t know that was definitely going to work, because in England you’d have been told to go away – probably using swear words. Something might’ve been said about your mother. In the editing we have things like a close up of Tom and then a close up of an audience member, trying to show that relationship that the band have with the audience. When that finger comes down to press that button and start a sample, the next shot will have 50,000 people freaking out. It’s powerful stuff, really, and you can’t help but connect."

Connecting moviegoers with the show is achieved via some masterful tweaks to the sensory bombardment. For one, the audio mixing absorbs the crowd sounds so deftly that it quickly became confusing as to just who was applauding – the live cinema audience or the prerecorded festival attendees. So effective was this connection that the two were one by the end of the screening: it wouldn’t have been surprising if some people were thrown by the lack of necessity to loosen their wellies from the suction of mountain mud as they broke for the aisles. But then there are other instances when the Fuji Rock crowd is left behind as a particularly intrusive visual arrives to issue an intracranial backhand, causing several people to leap out of their seats and let loose in front of the cinema screen as if it was actually the one showing visuals behind the Chems.

Don’t Think is just about as ferociously immersive as technology permits. There’s only one way it could be more so, but it’s easy to imagine that a 3D version would leave you with a massive post-rave come down.

"We almost went down that route actually," reveals Smith. "But it was too complicated and too expensive. It restricted what you could do. I really wanted cameras in amongst the audience and it would have meant rather than have 20 cameras you can have seven if you’re lucky. It would have been very different. I think it would have been a great thing to do, but it would have needed a lot more planning and a lot more money… Did you see the U2 one? As talented as they all are, I’m not sure if I want to see an extreme close-up of a middle-aged man straining his vocal chords in 3D."

We’re a few years away from BBC Glastonbury footage that could have you blinking into the glare off Beyonce’s thighs, or allow you the pleasure of tripping over a grown man in a ball gown lying fetal in the muck, but this could be the next step. According to Smith, theatre groups such as Punch Drunk and Secret Cinema have got the right idea: plays that go on around a wandering audience rather than in front of them. "I think taking the tradition of just watching the stage and breaking that down is really exciting. That’s the next level. I’d love to make the visuals come to life, like suddenly you have clowns tapping you on the shoulder and taking you off on little adventuress, or having every bit of the music represented by a different character."

The only problem with turning a documented gig into an immersive art installation is that it involves trusting that the spectator will see what the director wants them to see – an idea that might not sit well for many people in the profession, Smith included. I bring up the idea of customizable footage, like Muse’s interactive stream of a Wembley Stadium gig a few years back. Fans could choose from seven different cameras and even adjust the angle of each one. Smith sounds almost disgusted: "I’ve heard people talk about taking old footage and letting the audience choose which camera they view it from, and I just thought, ‘You know what? That’s what I do!’ I’ve been putting cameras in places and editing stuff for 20 years. There is a craft to it. I mean, not to put [customizable footage] down, it’s interesting, but it’s just not my thing."

It might seem a little controlling to assume that the audience doesn’t know best what they want out of an experience, but who better to record the spectacle than the man who created it in the first place? Don’t Think is a film about Smith’s own work that recreates the experience in the way everyone on that mountain in Fuji was meant to have it.

"In the end, it was just about documenting it," he says. "This thing we’ve been doing for 18 years. The film just captures a moment in time that tells people what they were up to back then. It’s something I can show my grandchildren and say: ‘See, that’s what we used to do. Freak people out.’"

For more information and a list of screenings check the Don’t Think website.