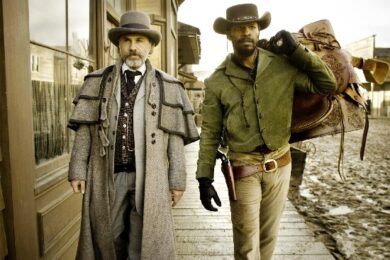

Since the release of Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained, there has been a storm of conflicting opinion about its controversial subject matter. Critics have variously bemoaned the film’s glorification of gun violence in the wake of the Newtown tragedy, the relentless use of racial slurs throughout, and the underlying problem of a white director reimagining the horrors of slavery as an exploitation movie.

Tarantino’s position on the link between filmic and real life violence is well documented. He has argued convincingly that the focus of debate should be on gun access and mental health, not the content of action films. And while the director has faced controversy before about the overuse of racial epithets in his work, at least on this occasion, a case can be made for the historical accuracy of the language used. The thorniest issue by far, however, concerns Tarantino’s appropriation of a black slave narrative as the basis for a spaghetti western.

Spike Lee was quick to denounce the film ahead of its release, commenting that he thought it disrespectful to his ancestors and he would not be going to see it. An unsurprising reaction considering his previous criticism of Tarantino’s heavy use of racially-charged language in his scripts. African American writer Ishmael Reed objected more forcefully, labeling the film an "abomination" in an incendiary article for the Wall Street Journal.

Criticism of the film inevitably hinges on whether it is perceived as racist or otherwise, but the complex issues it raises seem to defy such easy categorisation. Its vexing qualities are in some ways a strength, in that the viewer is continually wrenched out of the entertaining spaghetti western pastiche they think they are watching, to be confronted by the worst horrors of American history, again and again for almost three hours. It is an uncomfortable and troubling experience, and the dissonance it provokes forces you to question your passive consumption of such a film. Whether this effect was intentional or not, the viewer is at times made complicit in the dehumanising brutality that they have previously been perceiving as entertainment. Awkward parallels are drawn between the audience and the slavers relishing the bloody spectacle of the Mandingo fighters. As objectionable as elements of its premise may be, few other multiplex blockbusters intentionally put cinema goers on the spot in quite this way.

Django Shoots First

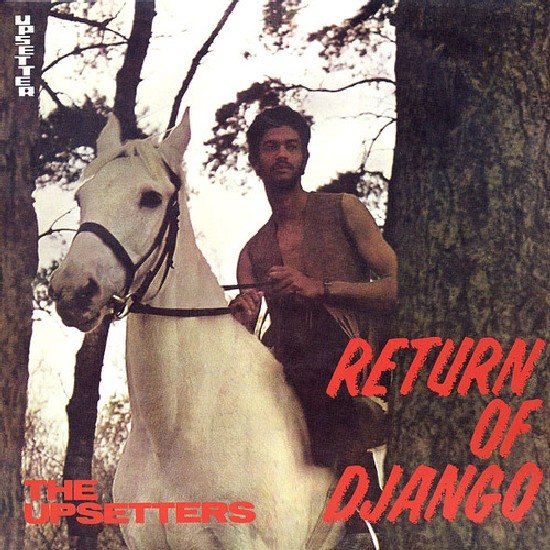

On the surface of things, it seems somewhat random to have made Django an African American slave in the deep south. In the original spaghetti western of that name, directed by Sergio Corbucci, the lead is caucasian. There have been more than thirty unofficial sequels to that film, and in each of them Django is played by a white actor. For this reason, the collision of western cinema tropes and a black slavery narrative appears crass and exploitative. But for anyone familiar with 1960s Jamaican reggae, the notion of a black Django makes perfect sense and perhaps even fulfills dread prophecy.

In 1968 Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry & The Upsetters released the track ‘Django Shoots First’, taking its name from the titular 1966 Django sequel, and voiced by DJ Sir Lord Comic. This was followed by a whole album from Perry & The Upsetters inspired by the Western series called The Return of Django in 1969. Prince Buster released a track called ‘Django Fever’ the same year, over the ‘Everything Crash’ riddim by The Ethiopians. Spaghetti westerns (as well as kung-fu films) were as much of an influence on Jamaican music and culture of the period, as they are on Tarantino’s films – and this is nowhere more evident than in a key scene of 1972 Jamaican crime film The Harder They Come.

In the sequence, Jimmy Cliff’s rude boy protagonist goes to the cinema and watches the original Corbucci Django film on the big screen. It is the segment where Franco Nero’s Django is cornered and hopelessly outgunned by a racist, red mask-wearing clan of outlaws – an obvious allusion to the Ku Klux Klan. At the last moment, Django flips open the coffin he has been dragging around throughout the film and produces a Gatling gun which he uses to spectacularly dispatch his aggressors. The inclusion of the footage both foreshadows the shootout at the climax of The Harder They Come, and seems to suggests something about the systemic racism and economic oppression faced by the character, and his gravitation towards gun violence as a means to overcome his situation. A theme extended to its natural conclusion in Django Unchained.

Jamie Foxx’s performance as Django, and the phonetic similarity of the name, is somewhat suggestive of Shango (also rendered Chango or Xango), the West African god of fire, thunder and lightning, masculinity and justice. There is even a 1970 knock-off Django sequel actually titled Shango. Shango was the historic fourth king of the Yoruba, who became a deity popular throughout the magico-religious traditions of the African Diaspora, notably in Cuba, Brazil and Trinidad. He is concerned with power, and his emblem is a double-headed axe that is symbolic of the use and abuse of power. Devotees of Shango often call upon him for protection, as his mystery is about triumphing against the odds, conquering fear, overcoming seemingly insurmountable difficulties and defeating one’s enemies even when you are outnumbered. Shango always finds a way to win.

Foxx’s Django is very much a hero in the Shango mold, a powerful African male whose force of will cannot be kept down. He frees himself from tyranny, takes on impossible odds and brings a fiery justice to his foes. Django uses fire to dispatch his enemies on more than one occasion; and at the beginning of his journey, Waltz’s dentist sidekick compares Django’s mission to that of the Germanic hero Siegfried – the only man who is unafraid of the ring of fire that surrounds the captive Brunnhilde. In an interview, Tarantino stated that Django and Brunnhilde/Broomhilda (whose surname is given as Von Shaft) are supposed to be the great, great, great grandparents of the blaxploitation character John Shaft, another unstoppable masculine hero after the Shango model.

In Yoruban legend, Shango is married to the river goddess Oshun, whose sacred colour is yellow. Interestingly, when Django dreams of his captive wife, she appears in his visions either partly submerged in the river or wearing a yellow dress. The 2012 martial arts film The Man with the Iron Fists, written, directed by, and starring the Wu-Tang Clan’s RZA (and "presented by" Quentin Tarantino) features a kung-fu blacksmith character, played by RZA, who was intended to also feature in Django Unchained creating a crossover between the two films. A younger version of RZA’s blacksmith was to appear alongside Django as a slave on the auction block, before being exported to the Far East for the events of his own film. Conflicting shooting schedules prohibited RZA’s involvement in Tarantino’s picture. But had this gone ahead, the RZA character would have been a perfect fit for Ogun, the Yoruban god of iron, blacksmithing and combat, who is the brother and rival to Shango. It is unlikely that any of these references to the Yoruban gods are intentional, but nonetheless they are there. Ancient African heroes remixed and reversioned through time, embedding themselves into a modern narrative with or without the knowing collusion of the author.

Tom Shot The Barber

Samuel L Jackson is barely in Django Unchained and his handful of scenes come near the end of the film, but his performance as a manipulative Uncle Tom overshadows the story. In very little screen time he reveals three layers of the character, the sycophantic house slave hanging off his master’s table and laughing at his jokes, the mean house overseer who rules the kitchen with a rod of iron, and finally the arch-manipulator, helping himself to the master’s brandy and bestowing Machiavellian advice. The hidden power behind the throne at the Candie Land plantation.

Jackson is playing against type as an Uncle Tom, and is almost unrecognisable in the role. His subservient, Dickensian house slave is some distance from the characters he is known for playing in Tarantino’s pictures and in his career in general. However, during a spat following the release of Jackie Brown, Jackson was accused by Spike Lee of being Tarantino’s "house nigga" after he defended the film and the director’s overuse of racially provocative language. In his review of Django Unchained, Ishmael Reid referenced this jibe with the cutting line "Samuel L Jackson plays himself".

In this context, there is something a little perverse about Tarantino deliberately casting Jackson in that role, unless it is intended as some manner of bizarre return jab at Lee. Interesting parallels are also drawn between Django impersonating a black slaver and Jackson impersonating an Uncle Tom – and over the course of the film we are shown that the Uncle Tom persona is itself a strategy for obtaining a measure of power in a hostile world. It is suggested that even the limp affected by Jackson’s character could be subterfuge employed for decades to exempt himself from field labour.

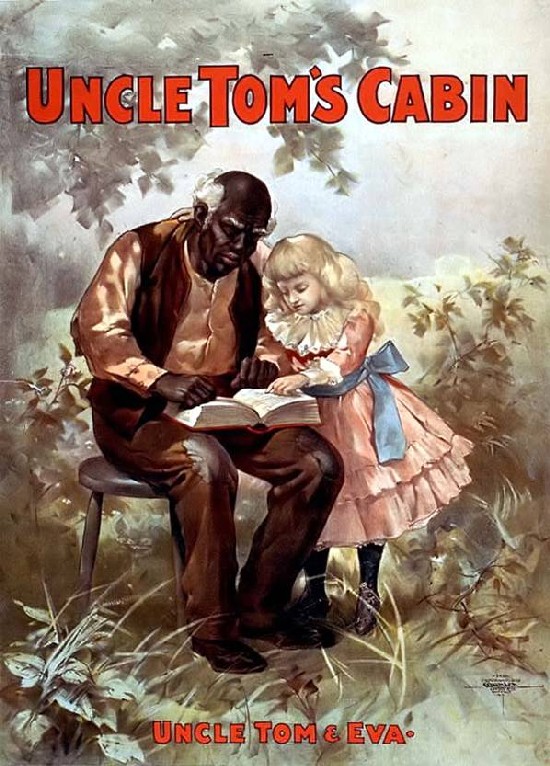

The figure of the Uncle Tom is a complex one. The name is taken from a character in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. While the book is of its time and filled with offensive stereotypes of African Americans, it was written as an abolitionist tract condemning slavery. It became the best selling novel of the 19th century and outraged the American South. When the author met President Abraham Lincoln at the outset of the Civil War, he is alleged to have commented: "So you are the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war."

The character of Uncle Tom in the novel is not the familiar sniveling, subservient half-man in thrall to a white master as suggested by the modern epithet. He is in fact depicted as a muscular man of strong character and Christian faith, who crucially rebels against the slave master on several occasions. He refuses to whip other slaves in the house when commanded to, and is savagely beaten for his insubordination – and is finally whipped to death at the end of the book for refusing to reveal the whereabouts of two escaped slaves. During his ordeal he prays that his aggressors be forgiven for their sins, and humbled by his martyrdom, the killers convert to Christianity themselves.

The modern notion of the Uncle Tom does not come from the book itself, but from the "Tom Shows" that became popular in its wake. Due to the lax copyright laws of the time, the author had no control over the dramatisations of her work that swept the nation. Minstrel show versions of the tale became popular, starring white actors in blackface, and often skewing the narrative towards a pro-slavery message. Here the Uncle Tom character was stripped of his strength and integrity, and recast as an asexual, decrepit old man with a receding hairline who invites everything he gets because of his weakness. The Tom Shows became more popular than the book itself, and the noble hero of the novel was neutered and emasculated to suit a racist agenda.

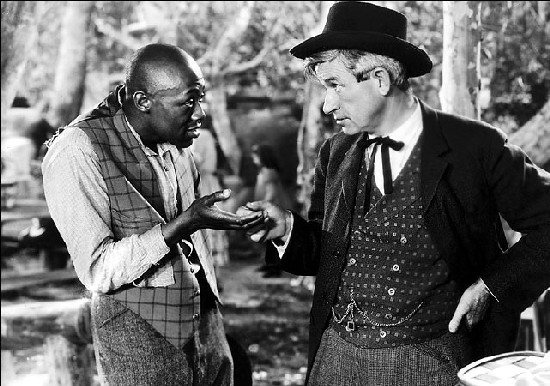

Jackson’s Uncle Tom character is called Stephen, which we can assume to be a reference to the controversial 1930s African American actor Steppin Fetchit, known for portraying lazy, slow-witted, jive-talking buffoons in countless Hollywood films of the era. Fetchit, whose real name was Lincoln Perry, is considered so offensive that few of his films are available on general release, and his contributions are often edited out of the running time if they are ever shown on television, regardless of its effect on the narrative.

Yet Perry’s persona as "the laziest man in the world" was developed as a vaudeville act with a subversive undercurrent. In a landscape where open rebellion was punished by violence and murder, the lazy, shiftless act – portrayed on stage by Perry – functioned as a way for black men to undermine white authority and deny their labour. The character’s jive talking would be heard as comical gibberish by white listeners, but to a black audience his skits were filled with satirical barbs aimed at authority figures.

Perry himself used this routine, both on screen and off, to play the Hollywood system and amass a significant fortune at a time when opportunities for black actors were slim. A fiercely intelligent, literary man who had a parallel career as a journalist for the Chicago Defender – he would often remain in Steppin Fetchit persona before and after auditions as a strategy for manipulating the expectations of racist whites. He would sometimes slur or mumble lines that he found offensive, pretending that he was too stupid to follow the script.

Perry was the first African American actor to become a millionaire, with a fleet of 12 cars and a staff of 16 servants. His trailblazing career opened the way for the generation of black actors who followed him, but his on-screen persona popularised and reinforced a humiliating racial stereotype. Yet in some ways, the Steppin Fetchit character is squarely in the tradition of physical comedy – he is playing a clown, quite a surreal one at times, and his act is no different to the comic routines of countless white actors. The problem lies with the racist culture observing his performance that assumes it is somehow a valid representation of what all black people are like. An equivalent would be assuming that all white people are exactly like Norman Wisdom or Stan Laurel, or that Harpo Marx is a fair representation of the typical caucasian.

Perry filed for bankruptcy in 1949, having spent all of his fortune. By the 1960s he was penniless and found himself out of favour with the times, seen as an embarrassment by the Civil Rights movement and his work universally reviled. However, in an odd turn of events, he became friends with Mohammed Ali after allegedly teaching the boxer a punch that he later used in the ring to floor an opponent. Perry then became a part of Ali’s entourage and eventually joined the Nation of Islam.

Samuel L Jackson’s performance as Stephen the Uncle Tom contains these stories. He is the villain of the film, but it is a film about performance and the acts that are adopted for survival. From the theatrical entrance of Waltz’s character, to the various personas that he and Django adopt throughout the film to accomplish their goals. Foxx’s Django risks losing himself to his necessary performance as a black slaver, watching impassively as a man is torn apart by dogs. Jackson’s Stephen has long ago lost himself to his own performance.

Fire Inna Babylon

One of the more problematic elements of Django Unchained is its depiction of a triumphant revenge fantasy that was simply not the experience of the people who actually lived and died under slavery for generations. Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds creates a similar discomfort. It didn’t happen. A Jewish black ops team didn’t get the satisfaction of riddling Hitler with bullets. Enslaved Africans did not get to break their chains, kill the slavers, torch the plantations and ride off into the sunset.

Except when they did. In 1836, during the Second Seminole War, more than 385 plantation slaves allied to the Black Seminoles rose up in rebellion, murdering their captors and burning 21 Florida sugar plantations to the ground. The Black Seminoles were Maroons, escaped African slaves and freemen who had gone native in the wilderness, forming bi-racial alliances with the Seminole Indians, intermarrying and exchanging cultural traditions.

From as early as 1687, the Spanish – who at the time held Florida – encouraged African slaves from the British territories of South Carolina and Georgia to escape south into Florida where they would be granted freedom and sanctuary, in exchange for defending the border and curbing British expansion. The African volunteers were organised into a militia by the Spanish at St Augustine, and their settlement at Fort Mose became the first legal free black town in America. However, many escapees simply vanished into the vast terrain after they crossed the border and created their own free settlements.

Florida was taken over by the British in 1763, but the lightly settled area remained a refuge for fugitive slaves. During the chaos of the American Revolution, more escaped slaves found their way to the Black Seminole territories and their numbers grew. By the early 19th century, slave-owning Americans in Florida were becoming increasingly perturbed by the many well-armed, self-governing black and Indian communities that existed on their doorstep. The three Seminole Wars took place between 1814 and 1858, and were intended to relocate the Seminole Indians westwards to the designated "Indian Territory" in Oklahoma, and to break up the dangerous Maroon communities.

Against this backdrop, the Black Seminole maroons sought to boost their numbers and maximise disruption by instigating widespread slave rebellion throughout east Florida. Hundreds of enslaved Africans liberated themselves from oppression and left the plantations in smoking ruins that could be seen for miles around. Whites fled the entire Eastern seaboard of St Augustine in fear. The Indians, maroons and escaped slaves waged a guerilla war for years, and won every major engagement of the conflict. After years of attrition, the Black Seminoles were offered their freedom in return for surrender and exile. While many of the escaped slaves were recaptured, a portion travelled west among the Black Seminoles to Oklahoma and their freedom. The emancipation of the Maroon fighters set a legal precedent that would be called on 25 years later to support the move to abolish slavery in the United States.

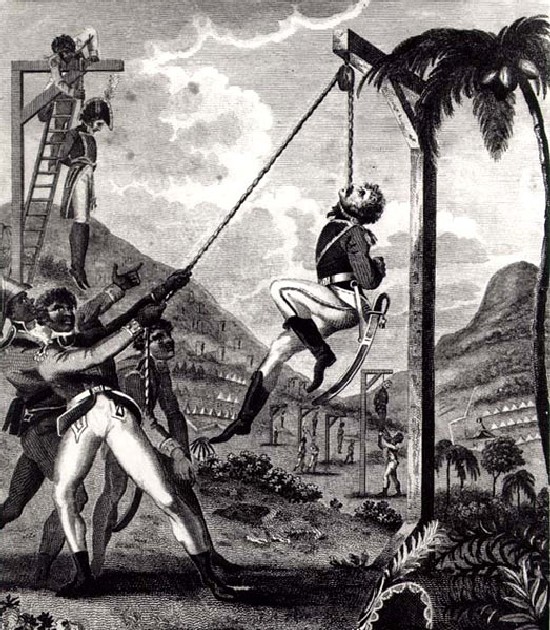

The facts of the Seminole wars were suppressed at the time. The escaped slaves were reported to have been "captured by Indians", and the whole conflict was described in the press as an "Indian War", with the Maroon component downplayed or excised in all instances. The notion of a slave rebellion on this scale was redolent of the Haitian revolution, an event that had sent shockwaves through the slave-holding southern states just 30 years previously. If slaves could violently throw off their chains and declare a free republic in Haiti, then the same thing could happen elsewhere. The suggestion that it already was happening in parts of Florida was unpalatable news. Even today, the Black Seminole-led slave rebellions tend not to be classified as such by historians due to the wartime context, and the largest and most successful slave revolt in US history is frequently consigned to a vague footnote.

Django Unchained portrays its slave rebellion in sensationalist and somewhat inappropriate Hollywood terms, but such uprisings did happen on occasion. There was a crossroads moment in American history where it was feared that the Haitian revolution spelled the shape of things to come throughout the world. That revolt had been directly inspired by the same ideals of liberty that had underpinned the French Revolution and the American War of Independence. However, when confronted by a black nation putting these much lauded principles of freedom and equality into practice for themselves, the tune suddenly changed. The newly founded Republic of Haiti found itself on the receiving end of crippling sanctions and massive war reparations that permanently affected its ability to thrive as a nation. Similar uprisings on US soil were either brutally suppressed or covered up.

While a director such as Tarantino was never going to offer the most tactful treatment of Django Unchained‘s emotive subject matter, it somehow picks away at a number of scabs that continue to fester. Westerns, like sci-fi movies, tend to say more about the period in which they are filmed than the period in which they are set. In this sense, Django Unchained offers a strange mirror.

Django Unchained is in cinemas now