There are plenty of reasons you could come up with to give Quentin Tarantino’s latest a wide berth. Django Unchained – a revenge saga set in the American deep South during the slave trade era – has ruffled feathers due to supposed insensitivity. Spike Lee has spoken out against the film, issuing the stern reminder that the slave trade was “not a Sergio Leone Western, it was a holocaust”, and that he would not be attending the movie out of respect to his ancestors. You might be suspicious that the film will amount to little more than an excuse for Tarantino to add to the disconcerting pile of n-words his often white characters have uttered over the years, often with a seemingly gratuitous, compulsive relish, as with his own Jimmie Dimmick in Pulp Fiction.

You may be put off by some of the more off-beam movies Tarantino has made since Pulp Fiction, such as 2009’s Inglourious Basterds, enjoyed by many but whose parallel history of World War II was too absurdly wishful for some, including the late Christopher Hitchens, who described its drawn out liberties as akin to “sitting in the dark and having a great bowl of warm piss poured slowly over your head”.

Or, there was Tarantino’s viral appearance on Channel 4 News, looking tense and pasty, as if he’d recently been picking straw out of his hair. It was, in its way, as striking as his performance as Jimmie Dimmick. He veered between describing the film as “a fantasy” and an attempt to initiate a debate about slavery, the like of which the USA had not had in 30 years in which the “Holocaustian, Auschwitzian” aspects of the trade were stressed. He snapped when Krishnan Guru-Murthy bowled him a gentle one about the link between cinematic and real-life violence. “I’m not your slave, and you’re not my master!” he declared, unfortunately, considering their respective hues.

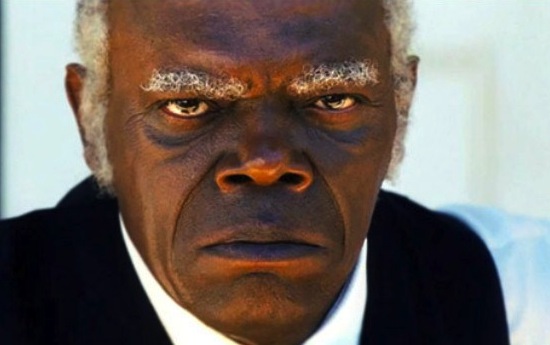

Cast all such doubts aside. Django Unchained is Tarantino’s best in years, a near-perfect movie taken on its own terms and boasting two of the most towering performances he has ever coaxed from his actors, courtesy of Samuel L Jackson and Christoph Waltz.

Its terms are pretty easy. Don’t for one minute take this as even attempting to depict the tragic realities of the slave trade (even though it is spotted with moments, performances even, when it plausibly does). It’s a postmodern movie, a movie about movies, among them the Spaghetti Western series, Blazing Saddles, the 1959 Italian epic fantasy Hercules Unchained and a hint of Gone With The Wind. Christoph Waltz, the villain of …Basterds, is brilliant as a silver tongued good guy here, a confection of erudition and casually lethal marksmanship; a bounty hunter posing as a mobile dentist who rescues Jamie Foxx’s Django from a slave gang. As the pair form an alliance, Foxx proves himself an almost supernatural marksman, which requires considerable suspension of disbelief considering his sole practice is in taking a few potshots at a snowman.

The film duly develops into a bloody tomato soup feast for those who like seeing 19th century racists take a blastin’. There is a wonderful scene in which some of the locals gather together into a proto-Klan posse known as the Regulators. It sits a little oddly, but is redeemed by its hilarity as it raises a practical point about the many inconveniences of riding in hoods. The mood is near Bugs Bunny cheerful – fake blood practically splashes out of the screen. And yet, the killings are edited and framed with supreme intelligence, the sleight of hand of a man who knows his popcorn and knows above all what great, cathartic cinema is about. Significantly, the one really poignant and unpleasant death is flinched from in the editing. The pair shoot their way to their ultimate destination – Candieland, where Django’s estranged wife is kept on the estate of Leonardo Di Caprio’s hideous plantation owner whose cruelty is only overshadowed by his retainer and elderly “house n****r” Stephen. Samuel L Jackson plays the servant who has so fully internalised the racism of his day, and his place in the scheme of things, that he enforces it as violently as any Klansman. It could be Jackson’s finest screen performance to date.

The object of the rescue mission, Django’s wife Broomhilda, is a plot device of few words but that doesn’t matter – the rest of the female African-American characters featured twinkle with sass, rather than conform to passive, eyes-cast-downwards type. As for Foxx himself, while hardly carrying the movie, he morphs very effectively into an Eastwood-esque, Man With No Name type, with all the attendant ruthlessness and unsentimental single-mindedness that entails. Some have found the concluding scenes of the film problematic but best to view them as a Brechtian device, a subversive reminder of what is real, and what is cinematic wish fulfilment, issued by Tarantino, the past master of what you want.