The late 1960s in America was a time of shifting attitudes towards sex, homosexuality, drugs, religion, race and war. A creative group of young misfits in suburban Baltimore embraced the drugs, experimenting with pot and LSD, but also experimenting with their sexuality, marking themselves out as deviant opponents of the status quo in the process. One of these young misfits, John Waters, was inspired by underground movies from the likes of Andy Warhol and the Kuchar Brothers to start his own production company, Dreamland Studios, (located at his parents’ house and then a rented slum apartment in downtown Baltimore) with which he created his own subcultural movement, dedicated to pioneering bad taste filmmaking.

Out to shock, disgust and make people laugh, he managed to meet some like-minded friends along the way, and these were the people who became known as The Dreamlanders. These early cast and crew members were Mink Stole, Susan Walsh, Mary Vivian Pierce, Pat Moran, David Lochary and Harris Glen Milstead, a mixture of party kids, art school and film school drop outs, with a DIY attitude and an anarchic spirit determined to rebel against small minded suburbia.

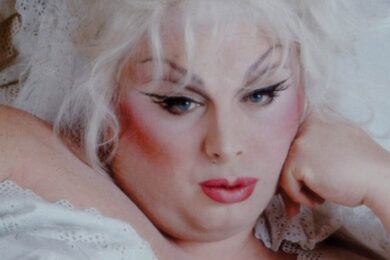

Harris Glen Milstead met John Waters when he was an overweight sixteen year old and they became firm friends for life. Glen was christened Divine by Waters, who thought an inflated, male Jayne Mansfield would make “the most beautiful woman in the world.” Divine became the most famous of the Dreamlanders cast thanks to his outrageous on screen persona and dedication to drag, both of which eventually helped ease him toward a music career as well as a stint acting on stage.

Roman Candles was the first short film Waters made with Divine. It was shown triple projected in the basement of a church in Baltimore with permission from a priest who encouraged Waters’ creative streak. In Eat Your Makeup Waters had Divine dress up as Jackie Kennedy to re-enact the assassination of JFK. Made only two years after the 35th President’s death it was absolutely in fitting with their bad taste ethos. Their second feature, Multiple Maniacs, features Divine getting rosary beads shoved up his ass in a church whilst the story of the crucifixion is played out behind him, as well as a charming scene depicting his rape by a giant lobster. Bearing a resemblance to his idol Elizabeth Taylor, with a dark wig, long lashes and a low back dress, his performance is one of no-holds-barred enthusiasm. The perfect partner to Waters in their lampooning of the director’s Catholic upbringing.

Divine’s break came in Pink Flamingos where he took on the blonde bombshell look most of us will be familiar with. Waters’ filmed Divine walking down the street in full drag and caught the shocked faces of the onlookers. A shaved-back hairline made room for his excessive eye make-up, a look dreamed up by Waters who wanted Divine to be a cross between Jayne Mansfield and Clarabell the Clown. The now infamous dog shit eating scene is still gag inducing, but it was a stunt that worked to garner the attention both Divine and Waters were looking for. The film was embraced by the Midnight Movies movement and its success allowed it to tour the country with New Line Cinema taking on distribution.

In the book Shock Value, John Waters devotes a chapter to Divine, interviewing him about his troubled childhood, during which he was bullied for his appearance and effeminacy. At a time when homosexuality was treated as a developmental maladjustment, Divine’s insecurities at being different forced him to the outskirts, making him a perfect fit for The Dreamlanders, who took a stand with their filmed homages to trashy splendour. Society saw them as perverts so they decided to revel in their status and take it to the extreme to make their point.

Waters is cited as saying Divine’s finest performance was in Female Trouble, the film in which the actor literally has sex with himself as he plays both Earl Petersen, a grotesque alcoholic, and Dawn Davenport, a horny teenager. The couple conceive a child on Christmas Day, but Earl leaves Dawn to raise their daughter Taffy on her own. This is Waters’ commentary on parenting, beauty and crime, and it bears an uncanny resemblance to the shocking way early sex education films portrayed women who indulged in sexual activity before marriage. Divine takes on a male role for the first time and, combined with his enthusiastic performance as Dawn – whose life is charted from truculent teen to psycho mummy – shows off his versatility as a character actor. Divine also did all his own stunts in Female Trouble, and let’s face it, trampoline flips and swimming across freezing rapids in full drag is no easy feat. Add to that the fact that he also sang the title song (with lyrics penned by Waters) and it’s easy to see why many think of this as his most memorable role.

Waters vehement objection to censorship is tackled in Polyester, where again Divine takes on the lead role as Francine Fishpaw, a holier than thou housewife with a nose for trouble. In Polyester (originally shown in ‘odorama’, ie with scratch’n’sniff cards!) Francine learns of her husband’s (played by 1950’s heartthrob Tab Hunter) affair, her daughter’s afterschool dalliances, and her son’s foot fetish through the power of smell.

It was around this point that Divine’s passionate performances, along with his strong fan base, started to attract other film directors. Paul Bartell cast Divine in cult comedy western, Lust in the Dust, after Tab Hunter recommended him for the role. He plays Rosie Velez, a thoughtful soul who dreams of becoming a saloon singer. The highlights are an elongated bar fight between Divine and Lainie Kazan and Divine’s hand on hip musical number. Divine also appears in Alan Rudolph’s neo-noir Trouble in Mind as Hilly Blue, another male role. Hilly Blue runs the underground activity in Rain City, his name spoken in hushed tones by the residents of this neon lit, smoky, saxophone soundtracked metropolis. Divine manages to hold a strong presence yet only appears a few times throughout the film, appearing in smart suits and slicked back hair as a villain. A subtle appearance contrasting nicely with Keith Carradine’s Coop whose hair keeps expanding and make-up getting more excessive as the film goes on.

The film that launched Divine and Waters into the mainstream and marked their first PG13 rating was Hairspray, released in 1988, the year Divine passed away. A bittersweet success story that was embraced in cinemas, on video and as a Broadway show. Set in the 1960s, Divine plays both Edna Turnblad, a mother who learns to embrace her daughter’s passion for dancing, and Arvin Hodgepile, a greedy supporter of racial segregation. Whilst there is an air of nostalgia for the era, with close attention paid to the hair dos, fashion and music, the revolutionary voice of the generation is spoken through Tracay Turnblad’s (Ricky Lake) opposition to racist attitudes. Though this can be seen as a gentler film than many of Waters’ previous efforts it still has the same spark from his earlier work as it celebrates the heroic outsider for speaking out against the establishment.

Divine and Waters sought to break down social taboos with humour. Looking back now on their collaborative work, twenty five years after Divine’s death, not only does their funny, sweetly rebellious streak come through, but also anger towards a society which has turned its back on them. It’s this anger toward the straight world – with its censorship and racism, its homophobia and intolerance – that ensures that a quarter of a century later this extraordinary run of films still have all the swagger and bite of their much-missed star.