Six characters keep trying to meet for a meal together but are continuously interrupted by miscommunication, death, sex, a restaurant running out of beverages, the police, the army, terrorists, and so on. Monsieur and Madame Thévenot, Monsieur and Madame Sénéchal, Don Rafael – the ambassador of the fictional Republic of Miranda (with the emblem on its embassy gate an impossible, upside down crescent moon over a palm tree) – and Madame Thévenot’s sister, the free-spirited Florence, represent the upper middle class in this wonderful surrealist comedy of manners. The superficial tenets that govern these figures’ lives are exposed as ultimately meaningless throughout ("merely arbitrary codes of etiquette", as Professor Peter William Evans puts it in his 1995 book The Films Of Luis Buñuel: Subjectivity And Desire). They’re reinforced by a recurring scene in which the six are shown walking purposefully, but obviously lost, on an open country road in the middle of nowhere.

Rumour has it that Marilyn Monroe inspired this bit of allegory. American author John Rechy recounts that the actress was visiting Buñuel on the set of 1962’s The Exterminating Angel, itself about a group of people unable to leave a room at a party. And very possibly, shortly after mentioning the "tiresome, uncaring people" the actors were portraying, she commented: "I see life as a long meaningless… talking, everybody just talking, obliviously." The director – by this time nearly deaf, and with a plane flying overhead at that very moment – misheard this as "walking".

Whether the anecdote is true or not, the image that made it into The Discreet Charm Of The Bourgeoisie is a powerful one. And Buñuel would also use the device of a jet engine roaring – or klaxon sounding or radiator clanging – to occasionally obscure important dialogue. The road motif can additionally be seen as a nod to The Milky Way (1969), whose characters travel the Way Of St James pilgrimage route through France and Spain. Indeed, in his autobiography My Last Sigh, Buñuel says that these two films plus 1974’s excellent The Phantom Of Liberty "form a kind of trilogy… all three have the same theme… all show the implacable nature of social rituals." The Phantom Of Liberty contains further hilarious commentary on dinner parties in a scene where the guests seat themselves on toilets surrounding the table. More referential fun in The Discreet Charm… comes from Don Rafael, played by Fernando Rey, being involved in cocaine smuggling, which alludes to the fact that Rey had the previous year starred as a drug baron in William Friedkin’s international hit The French Connection.

Don Rafael is the suave diplomat, full of shallow charm, who displays the utmost respect towards social convention while under the surface pursuing his appetites for sex and money. Ever concerned with public relations, he deals patiently with others’ ignorant or controversial views of his country, acting the gentleman towards all. He even shows interest when Florence (Bulle Ogier) speaks of astrology, an unsophisticated topic in such circles, revealing his zodiacal sign with the same birthday as Buñuel (February 22, "a Pisces, Sagittarius ascendant"). Florence herself provides the foil to this empty show of propriety by drinking to excess, vomiting out of car windows and complaining about the cello (Buñuel identifies her with the Surrealists here, many of whom, he claims, "detested music"). She is often seen looking bored (close-ups are rare in the film and yet two linger on Florence, surveying her surroundings with puzzled indifference or haughty disdain). Church and army soon enter the picture, themselves strict codes of conduct, and two of the director’s favourite themes. The Sénéchals hire their local bishop, Monseigneur Dufour, as their gardener (obviously ridiculous but not too far-fetched, considering the worker-priests of the ’60s) and the couple also let a marijuana-smoking army division billet at their home.

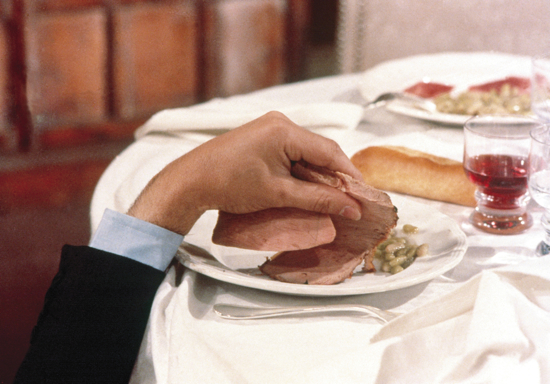

So deep rooted are these formal attitudes, this reverence for the façade of decorum, that these trapped souls can only get to their true feelings in their dreams. And even then these revelations have little or no impact on the pretenders’ lives. Awakening from a particularly violent dinner party nightmare, all Rafael seems to take from it is that he is still hungry. But the best illustration of this hypocrisy and repression, and an excellent example of how remarkably thorough the script is, is the character of Monsieur Thévenot (Paul Frankeur). Observe his comments during their second interrupted supper, completely disregarding culinary custom: "Even if I eat oysters or fish, I prefer red wine."

They settle for red, even though Florence wants a dry martini. At a later lunch she will insist on this cocktail, and Thévenot waxes lyrical on the proper procedure for preparing and drinking one (using Buñuel’s personal recipe). He then plays a cruel joke on their chauffeur, trying to demonstrate that the lower classes have no idea how to enjoy such a beverage. His wife rebukes him for this, and his beliefs are exposed as absurd, especially in light of his earlier comments. It is Thévenot too that Buñuel troubles the most in his sleep. For his subconscious is the only arena where he can confront the fact that Rafael is having an affair with his wife. This is expertly done (Thévenot even has a glass of port in his hand) and one is very much aware of the displacement, the levels preventing Thévenot from acting on his feelings.

Dreams, as ever in Buñuel’s work, are a vital feature of the action. He once told a producer, "Don’t worry if a movie’s too short, I’ll just put in a dream." But these sequences are never meaningless filler, far from it. Among all the other dining disruptions, members of the military relate their own hallucinatory memories to the party – in one case the telling of a "train dream" is itself interrupted and left unfinished. One assumes this is the director’s own recurring dream of being left on a platform as his luggage departs down the tracks, as recounted in My Last Sigh, where similar episodes show him using his own material for the fantasy life of the film. The soldiers’ reveries focus on their dead parents, leaving little wonder how they’ve come to embrace such an imposing sense of order.

There is, of course, much more to these curious accounts than that, and Buñuel did point out: "I don’t enjoy rummaging around in the clichés of psychoanalysis." Though with a sense that there is some rationale behind all this anxiety, we are far away from his and Dalí’s surrealist masterpiece Un Chien Andalou (1929), the irrationalist dogma of which had them hand out a flyer at its debut proclaiming ‘NOTHING, in the film, SYMBOLIZES ANYTHING’. To the end of his life Buñuel believed "the essential mystery in all things… must be maintained and respected." And it is wonderful that in these indiscreet dreams of the bourgeoisie there is much more than simply explanation, elements that will remain intriguingly indecipherable.

A digitally restored print of The Discreet Charm Of The Bourgeoisie opens theatrically this Friday June 29; a full list of UK and Irish screenings can be found here. The film enjoys an extended run at BFI Southbank as part of a season on its screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière, and will be released on Blu-ray (for the first time) and DVD on July 16 by StudioCanal.