In 1992, at the age of nineteen, I met Derek Jarman while I was walking along Old Compton Street in Soho. Having recently dropped out of film school in Canada, penniless and recently ‘out’, I’d gone to London (my mother’s hometown) in hopes of reinventing my new queer self. I bumped into Derek, literally, and after a brief conversation he invited me to accompany him on his errands. Over the course of a scant couple of hours he would give me some advice on filmmaking and, more importantly, advice on living as a queer man, that I’d keep with me for the rest of my life.

Already steeped in subcultural histories, I was a goth-punk hybrid and there seemed to be no room for me in the clone-heavy early 90s gay world. An outcast among the outcasts, I considered Derek a vessel of underground traditions and I devoured his biography, Modern Nature, as a guidebook on how to be gay at the tail-end of the 20th century. In those pages he was as fiery, furious, tender, mystic and jubilant as I could’ve hoped for. Most importantly, it was one of the first times I’d heard someone posit that my distinction from straight society was something not only to be protected and celebrated, but that being born homosexual was in fact some kind of marvelous gift. Four years later, when I sat down to assemble my first photocopied “queer pagan punk” zine, This Is The Salivation Army, I would continue to extrapolate from Jarman’s observations, combining them with other lessons learned from mutual inspirations and collaborators.

There was a great deal of palpable magic in Modern Nature, and indeed in the man himself: he greeted me like a garden, wide open, generous, full of variegated knowledge. Yet despite his effervescence, it was obvious that Derek was ill. He explained to me, matter of factly, that because of an HIV-related infection he had gone blind in one eye, or was going blind, so that if he wandered into the road I’d know why. He was hesitant, but I encouraged him to take my arm. I recall my world feeling very naïve and small compared to his, my problems trivial. Derek made every effort to make me feel otherwise, but (unusual for me then) I tried to stay quiet and listen as closely as I could. I was amused as he tried to dissuade me from making films several times, like one would coolly warn against the hazards of smoking. He even entreated me not to enroll in film school, but to choose art school instead. And, if I still had to make films, they should be about the people around me, my friends and my immediate circle.

Derek also advised me to return to Canada. Thatcher’s conservative Britain was a grim place to be young and gay. Clause 28 was in full force, similar to the legislation recently enacted in Russia, and Operation Spanner had locked up gay men for practicing consensual S&M and body piercing. I asked about his work with the artist Genesis P-Orridge, only to hear that the UK had become so hostile that Genesis, who’d been away caring for Tibetan refugees in Nepal, had decided it was safer not to return. When I eventually met Genesis, we talked about Derek and it cemented a lasting friendship. In fact, invoking Jarman’s name always seemed to yield the same mixture of profound respect and affection for a man who’d continually put his life, and his work, on the line for his beliefs.

As we wandered I got to see some of Derek’s everyday cycles unfold: I helped him select olives from a nearby delicatessen (I didn’t try them, to which Derek exclaimed “My dear, you must develop a taste for olives!” More advice, which I followed as dutifully as the rest); I sat at his feet while he got his hair cut and I told him about my latest unrequited crush, which he listened to great relish and sympathy; and I was grateful when we walked back to his flat so he could call around to friends to see if they could find unemployable-me a job. At one point he said that I reminded him of himself when he was my age, and then told me that I should learn to love myself. It caught me off guard. Of all the counsel he dispensed, this was the most baffling and difficult to manage, but it was sound. Finally he gave me his phone number in case I really got stuck. A few months lapsed, and I headed back to Canada to enroll in an art college.

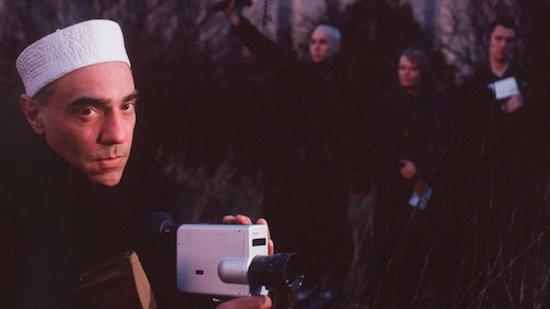

THE SALiVATION ARMY (Scott Treleaven, 2002) from S T on Vimeo.

I saw Derek only once more. We ran into each other on Old Compton again. His sight had become worse, and he told me that he was writing a treatise on colour (the crushingly beautiful Chroma). At the time I’d been so aware that Derek was perhaps near the end of his life that I respectfully never took advantage of the opportunity to call on him again, and for years after his death I regretted it bitterly. What I regret most though is the political and social machinations that tacitly allowed him, and thousands of others, to die. Having recently lapped 40, I find myself looking at designs for queer life in middle age. Instead I tend to see graves. The cultural loss that my generation has inherited weighs on me, and I find myself wishing that I’d overcome my shyness and tried to learn more from Derek, in person, when I had the chance. Nevertheless, I did exactly what Derek told me to do, following it to the letter, and my future sprang up from there. My first two films focused on the scenes that were burgeoning around me: in 1996 I made Queercore, the world’s first queer punk documentary, and in 2002 The Salivation Army, which detailed the rise and fall of the strange cult that had arisen from my zine. I even mitigated my filmmaking by increasingly devoting myself to drawing and painting. Yet along with everything he’d taught me in his books, in the roughshod brilliance of his Super8 films, and in that brief afternoon, Jarman also offered something else. His idea of queerness as a blessing of sorts turned out to be a radiant kind of permission; it means that we can slough off a past, an ideology and a trajectory, that’s not ours to inherit and keep on forging paths that are as yet unimagined.

Scott Treleaven (b.1972, Canada) is an artist and filmmaker. His film The Salivation Army, screens alongside Derek Jarman’s Glitterbug at the British Film Institute on March 15th and 18th. Scott Treleaven will be present at both screenings talking about his relationship to Jarman’s work