From the very beginning, Russian communism was cosmic, intergalactic in scope and ambition. Earth’s gravity would never be sufficient to reign in the forces unleashed by the Revolution. Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin, a close friend of Marxist theoretician Plekhanov, used to say that his music anticipated the coming revolution. He spent many years working on a grand synaesthetic composition, The Mysterium, to be performed in the foothills of the Himalayas: it was to last a week, and for a finale, bring about the end of the world followed by the birth of a new world and a new man from its ashes. Scriabin’s mysticism gave him affinities with the adherents of the Russian Cosmist movement, such as the proto-Transhumanist, Nikolai Fyodorov, who inspired the rocket pioneer Konstantin Tsiolkovsky.

The most direct influence of cosmism on the form eventually taken by Soviet communism came via the Martian novels of Alexander Bogdanov. Bogdanov was one of the leaders of the Bolshevik faction at the time of 1905 Revolution, a rival of Lenin’s. In the years following the failure of the first revolution, Bogdanov wrote a novel called Red Star which imagined a socialist utopia already fully grown on Mars. The novel’s detailed description of post-revolutionary Martian culture became the blueprint for the Proletkult movement for founding a proletarian culture in the years after 1917.

The October Revolution seemed to bring about an extraordinary efflorescence of science fiction writing, and the very first Soviet science fiction film, an adaptation of Jack London’s dystopia, The Iron Heel, was written by the Commissar for Enlightenment himself, Anatoly Lunacharsky (Bogdanov’s brother-in-law). Little is known of this film in the West today (though intriguingly, London’s original novel – first published in 1907 – predicted a Chicago Commune arising in October 1917), however, just a few years later it was followed by Soviet Russia’s first fully home-grown outer space fantasy, the first communist science fiction film to be based on a post-revolutionary Russian text, Yakov Protazanov’s Aelita: Queen of Mars.

Aelita was an event. The novel, by Alexey Tolstoy, had been the first undisputed classic of Soviet science fiction. The release of the film was preceded by extensive ‘teaser’ campaigns in Pravda and Kinogazeta ("What is the meaning of mysterious signals received by radio stations around the world? Find out on September 30!"). Alexander Exter, the film’s designer, was one of the few Russian futurists to have been on good terms with F.T. Marinetti and spent considerable time in Italy. She had taken part in the Salon des independents in Paris and socialised with Picasso and Braque. Special music had been commissioned to be performed by full orchestra in the cinema at screenings of the (silent) film. It was, perhaps, as film historian Ian Christie has argued "the key film of the New Economic Policy period." Its release was so successful that many parents named their children ‘Aelita’ after the eponymous Martian princess. Years later, it would lend its name also to a Soviet-made analogue synth.

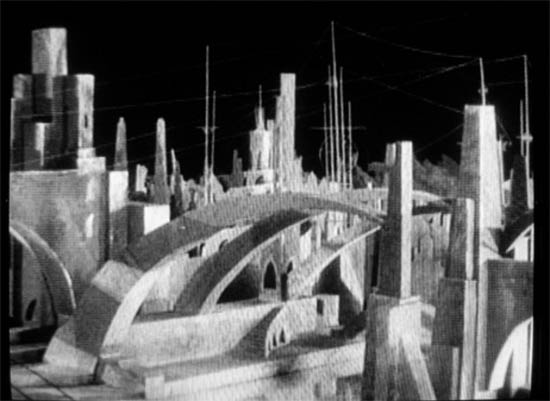

The plot, supposedly (according to Yevgeny Zamyatin) inspired by Rudolf Steiner’s Atlantis mythos, concerns a young rocket engineer, Loss. Against a backdrop of poverty and personal jealousy, Loss dreams of building a great spaceship in which to travel to Mars. In his fantasies, he finds himself the accomplice to the eponymous deposed and imprisoned alien princess and helps her lead a worker’s revolt against the despotic Martian elders, founding a socialist republic on Mars. But the real focus of attention is Exter’s jutting, protuberant production design; a constructivist massif of acute angles and swooping curves, like an El Lissitsky painting wrought in three-dimensions of harsh synthetic material.

The success of Aelita was immediately capitalised upon with a short and rather crudely drawn animation, Interplanetary Revolution: "An event" the titles of the 1924 short declares, "very likely to happen in 1929". Interplanetary Revolution promises "A tale about Comrade Cominternov, the Red Army Warrior, who flew to Mars, and vanquished all the capitalists on the planet!!" In which a lantern-jawed Dan Dare-alike in a red-starred uniform helps the Martian masses rise up against their bloodsucking bourgeois oppressors, the latter looking like nothing so much as bulldogs in tuxedos, grown fat on radiation poisoning. Our hero Cominternov looks on, laughing proudly as the capitalist pig-dogs go waddling off in search of safety on all fours, swastikas wobbling on their exposed backsides, while flickering somewhere in the backside sits Lenin like some curiously avuncular cosmic spirit – a role not a million miles from the one played by Bela Lugosi in Edward D. Wood Jr.’s first feature, Glen or Glenda.

The late 20s saw a dramatic fall in Russain SF output, with The Union of Proletarian Writers (RAPP) instigating a successful campaign against the genre in 1929-30. As Croatian literary critic, Darko Suvin put it, "Anticipating possible developments became a suicidal pursuit at a time when Stalin was the only one supposed to ‘foresee’ the future." All fantastic fiction became subject to a "theory of limits" or "theory of nearer aims" which insisted heroes keep to problems with shorter horizons. One film of this period worthy of some interest, however, is Vasili Zhuravlyov’s Cosmic Voyage ("Kosmicheskiy reys") which sees a woman, a small boy and a bearded elder gentleman flying to the moon on a rocket named Joseph Stalin. The plot is close to Fritz Lang’s Frau im Mond from seven years earlier and Zhuravlyov’s film can’t help but seem somewhat clumsy in comparison, but it is notable for some fantastic, gleaming futuristic sets and lovingly shot miniatures photography. Also, its sense of realism is considerably enhanced by the close attention of technical advisor, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, the pioneer of Russian rocket science whose writing would be a major influence on the engineers behind space programmes on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

Cosmic Voyage may be the first film in which a trip to the moon is a state concern, with CCCP proudly emblazoned on the side of the moon rockets, and as such the planting of a flag on the lunar surface acquires a signal importance, perhaps for the first time (for Robert Heinlein in America, nearly a decade and a half later, the moon voyage is still presumed to be an affair of private enterprise). But what is lost in this film is the almost messianic promise of interplanetary revolution. Cosmic concerns are ultimately subordinated to the a focus on the family unit (as in Frau im Mond) and the nation, with little of the utopian promise that animated Bogdanov and Protazanov alike. Cosmic Voyage is science fiction for the era of ‘Socialism in One Country’ (or at least, one planet), and the era of cosmic communism is over – until the death of Stalin, and a new generation of writers and film-makers, would re-animate it in the 1960s.

For details of the BFI’s Communist sci-fi season, please visit their website