Chris Marker, whose name was not “Chris Marker,” was a play of masks and avatars, an artist who leapt, like one of his beloved cats, from medium to medium. Walter Benjamin said that a great work (of literature) either dissolves a genre or invents one, that each great work is a special case; Marker produced a series of special cases. He invented the genre of the essay film; he composed what is widely considered the greatest short film ever made, La Jetée, in 1962; in the late nineties, he debuted one of the first major artworks of the digital age, the cd-rom, Immemory. Even Marker’s relation to his own celebrity—he wasn’t merely reclusive; he could be a generous correspondent, for instance, and he was always current, never turning his back on the present—was an evasive masterpiece: until his death in 2012 at ninety-one, he was everywhere and nowhere, refusing both the haughty fantasy of nonparticipation and the seductions of spectacle. How do you memorialize an artist who refused to remain identical to himself? How do you remember one of the great philosopher- artists of memory?

The appropriately unclassifiable book you are holding is a powerful elegy for Marker because it is a beautiful portrait from which the subject has gone missing. Colin MacCabe’s essay, interleaved with Bartos’ snapshots of the route to Marker’s studio on 3, rue Courat, is at once a poignant personal reminiscence and the finest appraisal I’ve read of Marker’s poetics and politics. The protean nature of MacCabe’s own work renders his encounter with Marker particularly rich. MacCabe has made crucial critical contributions to the study of literature, linguistics, and film; one cannot seriously discuss these disciplines and their interrelation without engaging MacCabe’s writings over the past four decades. And yet MacCabe is not just an influential academic: he was head of production and then the head of research at the British Film Institute from 1985–1998, and he is a producer, not just a deft reader, of important films, including works by Derek Jarman and Isaac Julien. What underpins all of MacCabe’s activity is a rigorous but adventurous interest in the relationship between culture and technology. He is that rare thinker whose deep knowledge of the history of art and politics is matched only by his openness and sensitivity to new cultural formations, new forces. It is no wonder—but it is the highest imaginable praise—that Marker welcomed MacCabe, as he would few others, into his immediate company, his conversation, and his studio, which, in Adam Bartos’ remarkable photographs, you are about to see.

People are everywhere and nowhere in Bartos’ photographs. The first book of his I encountered was International Territory (1994), a series of images of the U.N. Building in New York. Emptied of people, the architecture is left to dream its modernist dream of a future that never arrives. In many of the images, a distinctly post-apocalyptic feeling obtains: without a speaker atop it, the General Assembly podium appears like a giant tomb; the subtle signs of aging infrastructure—cracks in the walls, peeling paint—make the building feel less momentarily vacated than abandoned. I can’t quite decide, for instance, if the coat hanging in the photograph of the Russian Translation Service indicates that someone is working just beyond the frame or if the garment has been hanging there for years. The healthy looking office plants that appear in several images feel less like reassuring signs of habitation than like ominous indications that nature is starting to reclaim the buildings of a depopulated city. And the single rose in a vase at the center of the image of the Delegates Dining Room—is that freshly cut or plastic? I dwell on these details because Bartos’ photographs are full of such ambiguities, undecidable temporalities. Across his projects, I experience the contradictory sense that the human figure is just about to reenter the picture and that the architecture and furniture will never again be occupied. Of course, this shifting sense of presence and absence isn’t only an effect of what’s depicted, but of how— Bartos’ images feel both perfectly composed and simply found, patterned and yet un-manipulated, which means that my awareness of someone “behind” the camera dims and intensifies and dims again as I look.

The architecture dreams, the chairs expect—on a variety of scales, Bartos reveals how collective fantasies about the future are sedimented in materials. A few people do appear in Boulevard (2005), for instance, a book that juxtaposes images of Los Angeles and Paris—two historical centers of image making—but the pathos belongs to objects. Parked cars in an empty lot in Los Angeles or an unoccupied table for two at a Parisian restaurant (shot through the window from the street, but at an angle from which the photographer is not reflected in the glass, adding to the sense the image was taken by a ghost) seem to “wait without hope,” to quote Eliot, who Marker loved, for drivers and diners. The sense of waiting in Bartos’ work is key: What appears, appears to wait for the return of the human, but since nothing is as human as waiting, as the experience of duration that is boredom, I begin to invest things with feelings. And then the things look back at me.

Crucially, most of what appears in Bartos’ photos is dated; he depicts old futurisms, a special case of anachronism. Kosmos (2001)—I see a copy of this book on Marker’s shelf in one of the studio photographs—shows us the technologies and uniforms of Russian cosmonauts; Yard Sale Photographs (2008) explores that ritual suburban purging of barely resalable junk and memory. The shape of a fender, the linoleum of a counter, the outmoded ergonomics of an empty office chair, the now archaic instantaneity of the Polaroid, color schemes that register the collective affect of another age— we see in Bartos’ work period styles falling out of their periods. And Bartos is always depicting other media within his medium: books, cameras, old audio technology, etc. The quietly managed motif of discarded media makes each image feel “time sensitive”—the older technologies are, among other things, memento mori for Bartos’ camera, which adds an element of fragility to each picture’s quiet confidence.

Bartos’ most recent book, Darkroom (2012), gathers many of these concerns. His sense of composition can make even a photograph taken in the open air seem like an interior carefully arranged by a ghostly presence; a darkroom, typically an interior within an interior, is the nude of rooms, a site of exposure exposed. It is also the most dated of spaces, as digital technology has eliminated the dialectic of light and darkness once constitutive of the photographic art. Darkroom is an elegy for process and for patience, although, like many elegies, Bartos reinscribes the values he mourns, as his own photographs evince a sensitivity that makes nostalgia for a previous moment in the medium beside the point. These images of the displaced origin of images are again subtle evocations of distinct temporalities: the time required for photographs (of an instant) to develop in a chemical bath, technological developments that supplant that process in historical time. No photographer ever appears within the photographs, and Bartos’ touch is so light, it’s almost as if he’s given his camera a moment alone with the darkroom so that it can pay its last respects.

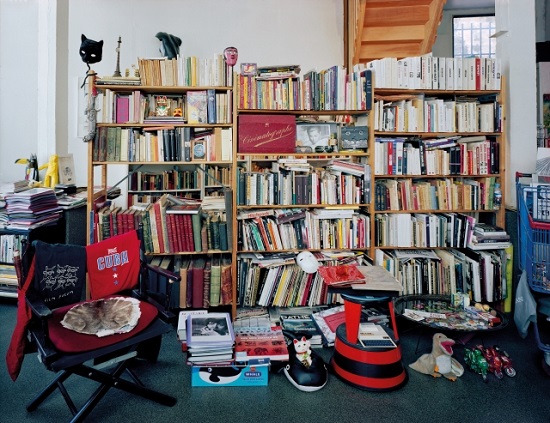

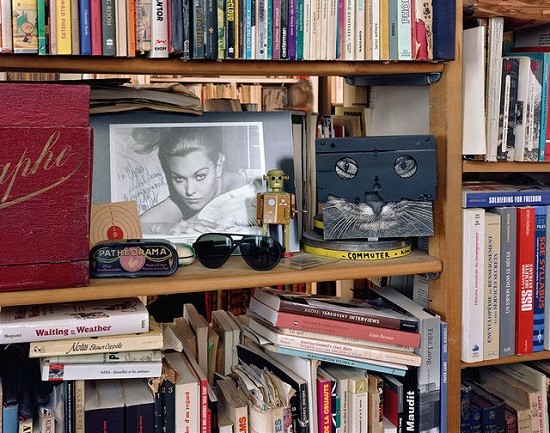

Prose can’t capture what Bartos captures in his photographs, but I hope I’ve indicated why he might have asked to shoot Marker’s studio, why the (in)famously private Marker might have assented, and why the result is so compelling. Marker is everywhere and nowhere in the photographs of his studio, which is both remarkably cluttered and remarkably clean. Beside the pile of Styrofoam and plastic awaiting recycling behind the VHS tapes in the first image, there is no trash, no dust; the thousands of books, VHS tapes, and CDs, the multiple computers, monitors, keyboards, and other production technologies all seem in their place. A sense of highly personal order prevails; Marker, I feel, would have just the right texts and images and totems at hand, but anyone else would be at a loss regarding how to navigate his systems. And, while Marker isn’t at home, from every corner something gazes at us: his cats and owls, Kim Novak in a signed photograph (Vertigo was Marker’s favorite film), the paused image of an actress on a monitor (in this book, Marker will forever almost be right back), masks of various sorts, stuffed animals, etc. Marker’s mind seems spatialized here, as though we were looking into his memory palace, an elaborate, idiosyncratic mnemonic become a memorial. But a joyous memorial: joyous first, because Marker’s signature mix of seriousness and playfulness is palpable—we see a thousand grins and winks—and second, because Marker, instead of becoming the fixed object of elegy, has again given us the slip, allowing us an intimate glimpse, but of privacy.

Marker’s studio is a kind of (light flooded) darkroom located off a Parisian boulevard and is as full of formerly futuristic keepsakes as a cosmonaut’s yard sale—that is to say, Bartos has been preparing, without knowing it, to shoot Marker’s studio for many years. But there is another way Studio has a remarkable rightness of fit with Marker’s work: Bartos isn’t just a photographer who occasionally collects images into a book, he’s particularly sensitive to the possibilities of the photographic book as a form, to the way local compositional decisions function in the larger syntax of the series, to the way images (here quite literally) unfold in time. I read Studio as a short film about Marker composed of stills—the paused images on the monitors heightening that effect. In the credits of La Jetée, Marker called the film a ciné-roman; Studio, too, is an experiment with montage, with dynamism and stillness. It is moving.

Studio; Remembering Chris Marker by Adam Bartos and Colin MacCabe is out now and available here