Whether through savvy or serendipity the Rolling Stones have always been in the habit of aligning themselves with only the most appropriate of filmmakers. Pick any one of their big screen outings and you’ll find a near-perfect correlation between the band at that particular moment and the man behind the camera. Setting aside the new HBO documentary Crossfire Hurricane (a cursory handful of theatrical showings masking its made-for-television origins), their most recent cinematic endeavour was 2008’s Shine a Light, a comparatively intimate gig captured for prosperity by none other than Martin Scorsese: rock’s elder statesmen as seen by one of cinema’s elder statesmen. Both can still draw a crowd and put on a decent show, but their glory years are long behind them and that vitality once so intrinsic to their work no longer exists.

Speaking of which, consider At The Max (made especially for the IMAX format) and its director Julien Temple. Once upon a time heralded as a key British talent thanks to The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle and his place among the first generation of music video makers, he’d since become cursed thanks to a string of disappointments, mediocrities and failures: the notorious flop Absolute Beginners; Mick Jagger vehicle Running Out of Luck (essentially a movie-length promo for his She’s the Boss solo album, shot in Brazil and co-starring Dennis Hopper); and oddball valley girl comedy/science fiction musical Earth Girls Are Easy. To be fair to Temple, he’s since picked himself up and carved out a niche as a noteworthy documentarian, but in 1991 his cultural value was negligible – much like the Stones themselves, in fact.

Of course it wasn’t always this way. The Rolling Stones once meant a great deal and that was duly reflected in their choice of cinematic collaborators. Jean-Luc Godard tapped their countercultural credentials (and, more specifically, ‘Sympathy for the Devil’) for One Plus One, a film that attempted to take the temperature of 1968 and in doing so placed them within a zeitgeist that also included Vietnam, Mao, Black Power and American imperialism. Meanwhile, Jagger was further cementing/trading off their outlaw status with starring turns in Ned Kelly for Tony Richardson and Performance for Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg, both released in 1970. He’d also recently supplied an experimental synthesiser score for Kenneth Anger’s Invocation of My Demon Brother, which happened to star Anton LaVey, founder of the Church of Satan, and Manson Family member Bobby Beausoleil; further outlaw associations that can’t have harmed their carefully cultivated image. And then it all spilled over into Gimme Shelter and Cocksucker Blues: real drug abuse, real sex, real death.

Gimme Shelter famously captured the ill-fated Altamont Speedway Free Festival that claimed the life of Meredith Hunter, stabbed by a Hells Angel for brandishing a gun. Its directors – Albert and David Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin – were practitioners of ‘Direct Cinema’, an objective and unobtrusive style that proved to be the perfect means of both documenting the immediacy of the violence and silently commenting on the numerous ironies that littered its build up. (Speedway owner Dick Carter states he "could do with the publicity"; Jagger claims the festival will "set examples to the rest of American society as to how one can behave in large gatherings".)

Cocksucker Blues, by contrast, was filmed by the photojournalist Robert Frank, previously responsible for seminal publication The Americans, Beat movie Pull My Daisy and the artwork for Exile on Main St.. Charged with recording the Stones’ 1972 tour of the US, his journalistic impulses took over resulting in a unique – indeed, essential – glimpse at life on the road. He recognised that cocaine and Truman Capote backstage are just as telling as a performance of ‘Street Fighting Man’ or a stage shared with Stevie Wonder. Likewise blow jobs on the private jet and roadies shooting up in hotel rooms. Needless to say, Cocksucker Blues has never seen a proper release as a result, though a court order does permit Frank to screen the film just once in any given year. (It was shown at Tate Modern in 2004.)

The Stones played it safe in the aftermath. Ladies and Gentlemen: The Rolling Stones was rushed into cinemas instead, offering up a far more conventional account of the Exile on Main St. tour. Inadvertently it also set the template for many of the concert movies and videotapes to come – slick, unadventurous, anonymous – and tellingly director Rollin Binzer would never receive another credit. The only notable exception (prior to the Temple and Scorsese efforts) was Let’s Spend the Night Together from 1982, which employed Hal Ashby. Here the Stones raced through their set list, seemingly impatient to get out of the various arenas and stadia they’d so easily sold out. The same attitude affects their director, insofar as Ashby does his job but little more; by this point he was a washed-up alcoholic and drug addict coasting off previous successes (he even overdosed during production, prior to a gig in Arizona). Any sign of the talent responsible for Harold and Maude, The Last Detail, Shampoo and the rest was hard to see, just as the band too were now a shadow of their former selves regardless of how many records they continued to sell.

All the while the greatest Stones documentary of them all was just being sat on. Charlie Is My Darling had been shot over three days in 1965 as the group embarked on a two-date tour of Ireland. It premiered the following year only to disappear from sight soon after thanks to a shift in management. Andrew Loog Oldham, who’d originally commissioned the film from director Peter Whitehead, was bought out by co-manager Allen Klein and ever since it’s existed in a kind of limbo, available only via bootlegs, bastardised versions or YouTube snippets. The problem wasn’t down to anything dubious in the footage à la Cocksucker Blues, but rather the music and who controlled its rights. Only recently have all of the issues been ironed out, finally prompting legitimate and uncut Blu-ray and DVD editions plus the obligatory deluxe box set that goes entirely overboard in an effort to snare the die-hards.

There’s a certain irony to this, given how Whitehead has since claimed that he’d never even heard a Stones record prior to Oldham’s phone call. He’d originally intended a career in chemistry before abandoning his degree at Cambridge to enrol at the Slade School of Fine Art. At the time Thorold Dickinson (best known for his 1949 British fantasy classic The Queen of Spades) was establishing a film department, and soon enough Whitehead was playing around with their sole Bolex. His first short, The Perception of Life, was fittingly scientific in nature – it was filmed entirely down a microscope – and it quickly led to work as a UK-based newsreel cameraman for Italian television. By 1965 he’d convinced the organisers of the International Poetry Incarnation (a gathering of numerous Beat poets, including Allen Ginsberg, Alexander Trocchi and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, at the Royal Albert Hall) to let him film the event with a single borrowed camera and made himself a calling card. Indeed, it was the resultant work – Wholly Communion – that prompted Oldham’s interest in the first place.

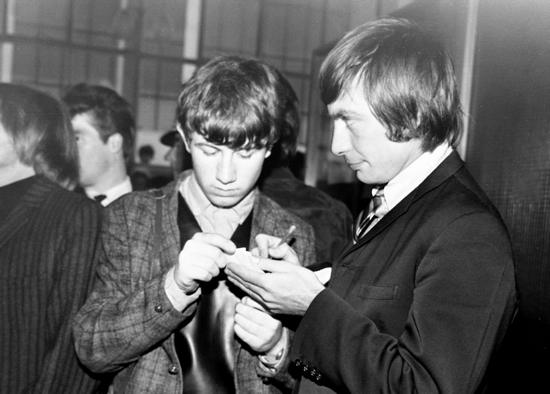

Whitehead’s newsreel experience greatly informed both Wholly Communion and Charlie Is My Darling. His technique was to point and record (rather than comment or intervene) and as such stands comparison with the ‘Direct Cinema’ and photojournalistic methods of Gimme Shelter and Cocksucker Blues. Importantly, Whitehead refuses to mythologise the group and this despite it being their first dedicated motion picture. (They’d previously appeared top of the bill in The T.A.M.I. Show, a 1964 concert movie put together by US drive-in specialists American International Pictures.) He’s curious certainly, particularly by their "shamanistic" qualities onstage to use his own words, but never once prey to hype or fashion. Whitehead was a little older than the ‘Swinging Sixties’ set and it shows: he’s not aloof, he simply treats the Stones as ordinary people. Admittedly the media image hadn’t quite been honed by this point, yet it’s fascinating to see them all as comparative innocents. We get Keith, not Keef. We get Charlie Watts awkwardly fidgeting on his chair like one of the schoolboy interviewees in Seven Up!. Only Brian Jones plays up to the camera and brings an air of pretentiousness to proceedings.

This level of intimacy and lowered guard would never be seen again. Indeed, many of these scenes would never be seen again, whether it’s the Stones being forced to run across a railway line in order to get to their car or Richards being pestered by fans who only want a touch of his hair. For the director it is these moments, more so than the musical performances, which genuinely interest. He shoots in long single takes, flitting between the band members and an ever-present Oldham, acting as a casual observer. It’s through the details, Whitehead suggests, that we can get to understand these people, however mundane those details may be. In fact, after fifty years of the Rolling Stones, it’s arguably this kind of mundanity that we crave.

There’s undoubtedly more to be gleaned from a minute or two of Charlie Is My Darling than there is the meet-and-greet with the Clintons that opened Shine a Light or any number of half-arsed run-throughs of the hits. Be aware, however, that the new discs bury Whitehead’s original director’s cut among the extras. The newer cut, created for this release and due to be televised on the Beeb this weekend, has more footage but also places a far greater emphasis on the live stuff. As well as scrubbing up the picture and sound, it also removes some of Whitehead’s fingerprints, resulting in a much more streamlined and ultimately less insightful document.

Post-Charlie… Whitehead became an inadvertent chronicler of the sixties. The Stones employed him again for various pop promos (including the Oscar Wilde-influenced ‘We Love You’ film which Top of the Pops opted to ban) leading to more of the same. The Animals called upon his talents, as did Pink Floyd, Jimi Hendrix, PP Arnold and plenty more besides. He also took his camera to various events and happenings and somehow managed to capture many of the decade’s defining pop cultural moments: Vanessa Redgrave singing ‘Guantanamera’ at the Royal Albert Hall; the 14 Hour Technicolor Dream at Alexandra Palace; Olivier performing at the National Theatre. Arguably many of these moments have become so defining simply because Whitehead was there, his footage endlessly recycled in countless retrospective/nostalgic documentaries.

Fittingly, he’d done much the same thing himself – reconstructing and reconfiguring his footage into different combinations, his own cinema feeding off itself. Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London, released in 1967, was the feature-length version, a kind of ‘greatest hits’ that borrowed from Wholly Communion, Charlie Is My Darling and the rest to gauge the times. It was subtitled a ‘Pop Concerto for Film’. Ten years later, much of the same footage reappeared for Fire in the Water, Whitehead’s final cinematic creation. Here a director hopes to create a requiem for the sixties out of all these metres of film he’s amassed over the years. He retires to a cottage with his girlfriend (played by Whitehead’s real-life partner of the time, Nathalie Delon) but ultimately burns everything as The Doors’ ‘The End’ plays ominously on the soundtrack (and pre-empts Francis Ford Coppola).

Fire in the Water was effectively disowned. Whitehead dubbed it a "non-film" that he was coerced into making. For him his contribution to cinema concluded in either 1969 with The Fall or 1973’s "tying up of loose ends" Daddy. The former was almost a US equivalent of Tonite Let’s All Make Love… using mostly documentary footage but centred on a fictionalised assassination. (Martin Luther King was killed on the first day of filming; Bobby Kennedy died on the day Whitehead returned to the UK.) Its final image was of its director trapped within the image – not only was the film eating itself, now it wanted its creator too. Daddy, on the other hand, was a collaboration with the sculptor Niki de Saint Phalle, and was once memorably described by J Hoberman of The Village Voice as "unforgettably unpleasant". Starting life as a documentary, it quickly transformed into a surreal fantasy in which its subject play-acted a series of sadomasochistic scenarios against her father.

After which Whitehead was spent. He turned his back on cinema and switched his profession to falconer, eventually gaining a position within the House of Saud (or at least until the first Gulf War broke out). As far as he was concerned he had nothing more to say within the medium which, this being 1973, couldn’t have happened at a more apt time. As said, the Rolling Stones worked with only the most appropriate of filmmakers…

Charlie Is My Darling is out now on DVD and Blu-ray via ABKCO Films and screens this Sunday November 25 on BBC Two. There is also a limited edition Super Deluxe Box Set retailing at £70.