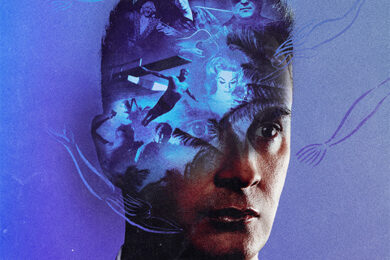

Despite them both being inspiring and loving tributes to unique independent filmmakers, Tim Burton’s 1994 masterpiece Ed Wood and Craig Brewer’s similarly sublime 2019 film Dolemite Is My Name have failed to see the artists at the heart of those screen stories receive the recognition they deserve for the work they made. There’s been a strange decoupling of the artists – held in high cult esteem as maverick, against-all-odds creators – and their art, regarded as laughably bad at best, downright atrocious at worst. This decoupling also occurred in 2018 and 2019 in a different space, with Nicolas Winding Refn’s dense and extraordinary byNWR archive project being much talked about and pored over upon announcement and launch, only for the content that has formed the heart of the project to have been utterly ignored upon release.

There’s an elitism and a snobbery at play here that is resulting in some of the most fascinating, electric, bizarre and oddly tender cinema ever made going completely unheralded. In an age where the slightest ripple in the film pool results in waves of pro/con response, this on the surface seems odd, until you realise that a lot of these films exist so far outside normal genre and commercial conventions that they also exist outside of a critical vocabulary for how to talk about them. But that’s where the fun lies, in working out what these films are and how to talk about them. Over the past few months I’ve been talking to all the key players in the byNWR project, including Nicolas Winding Refn, to find out more about the philosophy, collaborations and approach behind this amazing experience and resource.

ByNWR is a “cultural expressway”, in which Refn and his team release a restored film each month, for free, accompanied by a wealth of original responsive writing, photo and video archive material, live performances and other tangential ephemera. “Tangential” is the key word here, as so much of what accompanies the releases each month is a flight of fancy, or a barely traceable tentacle from the original source. The original source is an incredible collection of films, restored by a team led by Peter Conheim of the Cinema Preservation Alliance alongside partners including Academy Film Archive and Harvard Film Archive, and the filmmakers who made them. Refn doesn’t like the term “exploitation cinema” for the films, preferring to call them “pop cinema” and it’s true that all of the nearly 20 titles released so far on the platform, having been previewed on MUBI in one of the project’s key partnerships, defy easy categorisation. As he says, “Good or bad? Who cares?”. Released in volumes, with three films in each volume, where “a guest editor’s brain is on display for three months”, this “museum of cultural artefacts” has so far restored and (re)released stunning examples of cult, punk, propaganda and fetish cinema. The direction of the site and volumes comes from quarterly curatorial meetings between Refn, Conheim and editorial director Jimmy McDonough. Refn describes the process as leaving “the curating and choices to Peter and Jimmy. When they have selected a film, I watch it out of curiosity and I’ve had an enormous amount of pleasure seeing them.”

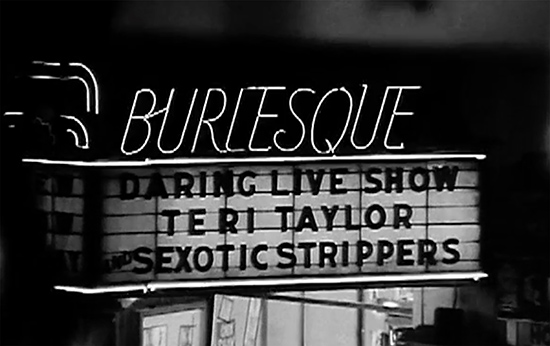

The writer Jimmy McDonough, author of acclaimed biographies of Neil Young and Al Green, is the “consigliere of byNWR”, and everything that goes out on the site goes through him. He oversaw the first three releases in the first volume, tilted ‘Regional Renegades’, and his approach set the content tone and feel in much the same way that Fincher did with Mindhunter, or Scorsese did with Boardwalk Empire. Every now and then, he dips back in as a writer with pieces for other guest editors and their volumes. His most recent piece was a 20,000-word, 400-image story on the carnival stripper and burlesque legend Georgette Dante, and he seems to be relishing the freedom afforded by byNWR, saying, “That’s a great thing about Nicholas, he just gives you carte blanche to blow your brains out and and that kind of thing really appeals to me.” I mention that despite the vastness of the internet, there are still very few places that encourage the kind of length and depth that byNWR is becoming renowned for. He replies: “Nic sold me on the Alice In Wonderland thing – that’s what he wanted it to be like, an adventure and something original. Hats off to him, and David [Frost] our designer. Most places online have rules and regulations, it’s got to be a certain way. Listen, Nic definitely had me in his face saying things like ‘people will want a contents page,’ but he didn’t want to hear it. In fact, he would have none of it,” says McDonough, laughing. “Nicolas couldn’t give a shit about making it easy. He wants it to be beautiful.”

It’s clear from spending time talking to Jimmy and Nic that they are kindred souls. Their collaboration is a passionate and feisty one, but they are always working to the same end: making the site a museum of human stories that takes figures from the fringes and brings them into sharper focus. As Jimmy puts it, “I love the human story, and what’s lurking behind a lot of these artefacts that we’ve dug up are many great human stories that don’t get told. Like Georgette [Dante]. I mean, she faced every obstacle in her way and yet she came out on top and was this great contortionist magician and a million other things. That kind of human spirit appeals to me, and I’ll document it whenever I can get the chance”. It’s a thrill to hear Jimmy talk about the characters whose stories are available to learn about on the site, especially as it wasn’t cut and dried that he would be involved. Despite helping Nic pinpoint titles of interest when the opportunity first arose to buy the collection of prints that form the backbone of Refn’s collection and the byNWR archive project, McDonough felt that, having spent a lot of time around the legendary 42nd Street fleapit scene, this was not a period of his life or experience that he wanted to revisit.

He’d been there the first time round and wasn’t in a hurry to revisit films he didn’t necessarily feel were worth the time. Refn changed his mind though. As McDonough says, “Nicolas has such a unique take on these films, it made me look at them in a whole different light. To hear him talk about a film like Shanty Tramp, or Murder In Mississippi is to hear his unique approach to what he thinks the films are really about. He really cares about and is interested in them and you can’t help but be inspired by that.” I tell him it’s so nice to hear him talk about their relationship and that listening to him, and reading McDonough’s initial introduction to the project in the first volume, reminds me of the relationship between Ralph Steadman and Hunter S. Thompson in terms of egging each other on and pushing each other to the limits of their potential and friendship.

He gets a bit choked up, saying it reminds him of something very personal, but agrees, and elaborates: “You hit the nail on the head. I’ve been lucky in my life to have a few great partnerships and this one is certainly the equal of any of them. It’s very tempestuous, there have been screaming matches and fights about it all. We’re very passionate people. None of it comes easy. But it’s extremely rewarding and I’m in it for that. He wants the best out of you and he’ll get it, even if it means pushing you to the end of your rope. I have a similar approach and all of it is in a sense of fun. Demented perhaps, but fun nonetheless.”

One thing I’m curious about when talking to the byNWR team is what their personal favourites in the collection are. For Jimmy, it’s Saul Resnick’s 1966 fetish drama cum faux documentary/public information movie Maidens Of Fetish Street. “It’s beautifully shot, so singular in its attack. It just blew my head off. And Peter [Conheim] and crew made it look so sublime. I was used to seeing these films on 42nd Street where the print had a big red line through it, you couldn’t hear the sound and it was like looking at a murky goldfish bowl. To see these things unveiled in such pristine fashion is a beautiful thing.”

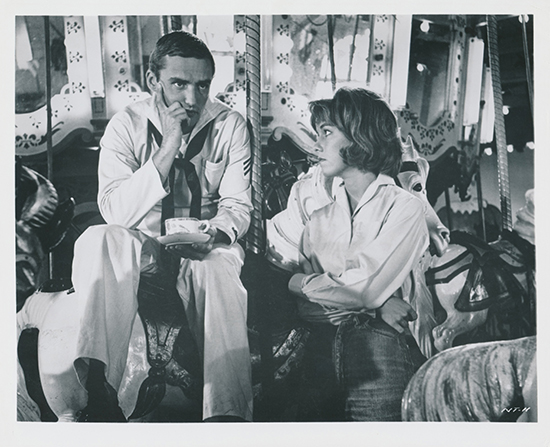

The person responsible for the pristine restoration of Maidens and the other films in the collection is Peter Conheim. When I talked to Refn, he was keen to constantly reiterate how invaluable Conheim is to the success of byNWR. So when I talked to Peter, I was keen to learn about the process of restoration and we used Joseph Mawra’s Deep South Civil Rights melodrama/grindhouse Murder In Mississippi as the case study, as it had just previewed on MUBI when we spoke. The element that Conheim and his team worked from was not an original negative, but simply the only 35mm print they could find, the only one known to exist anywhere. This was different to the early restorations that were from camera negatives, where “it was possible to make them virtually perfect or close to perfect”. The Murder In Mississippi print wasn’t in great shape, though, as it had served good time on the Drive-In circuit in the American South – a circuit like most Drive-In circuits not renowned for a high level of duty of care regarding prints. The restoration was approached as if it was the original negative, with all the resources and skills that the byNWR has at its considerable disposal, including supreme restorationist Ross Lipman as image consultant and Andrew Drapkin as the colourist/operator – but that doesn’t guarantee success. Conheim said, “When we work on a movie like that, all we can do is take our one print, and just try our best to resuscitate it image- and track-wise. In the case of that movie it was really hard. It was so compromised, and not just physically damaged. It was so dark. The night scenes had virtually no image on the film. We were able to do a lot and if you compare the previous transfers to it, you can actually see what’s happening in some of the shots that you literally couldn’t see before”.

I ask him if the limitations of restoration can be frustrating, which leads to a fascinating insight into the byNWR project and the relationship between Conheim and Refn as collaborators. Conheim describes it as so: “If there is a tension that exists amongst ourselves it’s around this. Nicolas’s aesthetic as a filmmaker is very different. He has a very glossy aesthetic, and when we first started doing this he really had it in his head that our restorations should be pristine, they should be the Rolls Royce of all restorations and I totally got where he was coming from. My job in a sense, as a preservationist, was to wean him off that. I felt I had to gently educate him to the idea that you can’t always – I love this expression – ‘make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear’”. Conheim goes on to talk about the tensions in the process of restoration, and it’s clear he reflects on them often. He talks about the “liminal tension” inherent in trying to honour the original vision of the filmmaker, but also the original artefact that came out of that vision and the place the artefact had in the world – be that on the Drive-In circuit or in Times Square fleapits. He calls the tension an “interesting game”, one he plays with himself over what to clean up, and what to leave. Ultimately he, Refn, McDonough and everyone involved with byNWR want that tension retained, for audiences and visitors to feel when they experience these films.

Conheim talks like a true collector, so I ask him about the hunt for these films and he regales me with a story about a warehouse in New Jersey with "thousands and thousands and thousands of films, I mean, literally”, most of which are uncatalogued and are the result of a laboratory selling off its elements over a decade ago. He has had his fair share of eureka moments in this vast space. “Every once in a while I found something and it was like ‘Holy shit do you realise what this is? This is the original negative of you know, blank, that’s been thought to be lost”. As with McDonough, I ask him for his favourite title of the bunch, and as with McDonough, he plumps for Maidens Of Fetish Street. This is after some consideration, as he admits it’s hard given how close he is to the physical process of restoring these titles for release. But Maidens, he says, “really exemplifies the best fucked-up-ness that is byNWR. That movie is so inexplicable in a way that only a single feature a director ever makes can be. It is so out of left field and I love it because it manages to be vaguely sexy, but not, not quite sexy enough which is partly why I think it’s great”. He also holds a special place for the supremely strange films of Estus W. Pirkle, an evangelical preacher, and Ron Ormond. byNWR has so far released The Believer’s Heaven, The Burning Hell and If Footmen Tire You What Will Horses Do?. All films take the form of direct-address sermons intercut with long dramatic recreation sequences of violent and desolate projected futures of doom for planet earth, in the forms of apocalypse and communism, where the only salvation is in the Lord. Conheim’s special pleasure in these films comes from the fact that they were never meant to be screened for the general public and doing so feel “blasphemous”.

What makes the byNWR project possible is the support and work of London creative agency BUREAU, which Refn singled out for a special mention when I spoke to him saying “One thing is the content, that’s 50%, but the other 50% is the presentation. And BUREAU have been able to, design wise, figure out how to actually present everything”. The everything being the "Alice In Wonderland" feel that Jimmy McDonough mentioned above. Refn says that “there are people who still complain about how to use the site” but it does what he wants, which is to feel like a museum, one where orientation is more maze like than instructional and “easy”. This approach to design, plus the amount of content, make spending time on byNWR a consuming experience, but one that as Refn says “asks for your time, but will reward you for giving your time”. One of BUREAU’s team, David Frost, already had a working relationship with Refn when conversation turned to what was happening with all those films he had bought. All parties were in agreement that they should be released for people to see, but also that just releasing them wouldn’t be enough, that they should be the catalyst for a “cultural expressway” with guest editors overseeing volumes of releases all under the curatorial and presentational eye of the core byNWR team.

I spoke to Jeff Boardman and Jules Hammond from BUREAU about working on byNWR. It’s clear from our conversation that their passion for these films and getting them seen matches those of the others I spoke to. They were also crystal clear about the sensibilities they look for in guest editors and contributors, “going wide with their approach, being edgy, not just finding subjects that haven’t been spoken about but subjects that should be spoken about, finding someone who wants to push boundaries”. One of the things I want to know is why a creative agency would want to be involved in a project where the content is given away for free. From talking to the other key personnel it’s clear why they believe in it, but what about Jeff and Jules et al? Jeff says, “One of the things we are getting out of it is a really good team of people that are really happy working on the projects and I think that’s massive for any agency or any organisation. We knew for two years that this was going to be an act of love, and we’re now starting to explore other avenues where we can do more”.

The other avenues include their first Blu-ray release in partnership with Indicator/Powerhouse of the Curtis Harrington’s mermaid fable Night Tide, featuring an early Dennis Hopper performance. This is Refn’s personal favourite of the titles he’s released so far, alongside the first release, The Nest Of The Cuckoo Birds. Also due this Spring is a book on cult director Andy Milligan titled The Ghastly One, written by Jimmy McDonough, and there’s the continued branding of Nicolas Winding Refn’s strange cine-televisual odysseys with Amazon such as Too Old To Die Young from last year, and the forthcoming Maniac Cop series with the byNWR stamp. On the question of their favourites from the collection, Jules from Tech Bureau says “You’re gonna laugh, but my favourite is House On Bare Mountain” – but I tell her I love it too. Jules describes how it reminds her of Carry On and Hammer Horror films and is a “beautiful marriage between ‘whoops my bra fell off’ Carry On stuff, schlocky, really shonky effects, Benny Hill and The Curse of Frankenstein all together in one glorious, weird, brain party.” She adds that her favourite aspect of working on byNWR is working with the team, with all the editors and writers and “finding this huge variety of new ways in which to explore the most amazing aspects of what these films can inspire. What questions do they raise, and how do we answer them?”. Jeff, like Nicolas Winding Refn, plumps for Night Tide, saying “it is an absolutely beautiful movie. When we first got it restored, we showed it at the Lumière festival in France and it was the first time I saw it on a large screen. Five minutes in and the whole place was quiet and just watching and it was so beautiful. I think the work that Peter did on that film to bring it back from where it was to where it is now is just stunning. It’s something I think everybody should see”.

Thanks to Indicator/Powerhouse, everybody will be able to see it in its full glory, as the film was released on January 22 in a stunning edition with yet more original writing and commentary. Until then, head to Nicolas Winding Refn and co’s “cultural expressway” and find a treasure trove of strange, unique cinema just waiting to be enjoyed, endured and engaged with.

Discover the riches of byNWR by clicking here