Almost two years ago to the day, Bruno Dumont’s sixth feature, Hors Satan, received its premiere at the Cannes Film Festival. This week, it finally arrives onto UK DVD. Such gaps aren’t unusual for the French filmmaker, but rather have become the norm. His previous effort, Hadewijch, endured a two-and-a-half year wait before playing British screens (a one-off engagement at the London Film Festival notwithstanding), while 2003’s Twentynine Palms effectively ended up going straight-to-DVD. Feature debut La Vie de Jésus took more than a decade to reach any home video format, appearing only for the tiniest of theatrical runs and a single screening on FilmFour (when it was still a subscription channel) during the interim.

This is the divisiveness of Dumont in a nutshell: a major auteur in the strictest sense of the word, but also a risky one. The various UK arthouse labels are hardly falling over themselves to pick up his work (to date, the spoils have been shared between four of them) and even when they do it rarely guarantees an immediate release. The love-hate divide that Dumont’s films prompt – second feature L’Humanité was infamously greeted with boos when it collected three awards at Cannes – seems to also extend to the distribution networks which is an interesting predicament. Here we have one of the most intriguing filmmakers currently working today, a man whose efforts always prompt a strong response in their audience, yet this appears to be what makes his films a dangerous prospect. So far we’ve been lucky inasmuch as the first six films have all made it to these shores, however late. And number seven, the recently premiered Camille Claudel 1915, stars Juliette Binoche which gives it a strong advantage. But will that luck eventually run out?

Dumont once described his entry to the film industry as being “through the window” rather than the front door. He didn’t go to film school, but studied (and eventually taught) philosophy instead. His earliest experiences behind the camera came from industrial documentaries, films about “the insides of tractors… notaries… ham…” that were destined for small audiences and often made solely for internal use. Here he toiled for the best part of a decade, teaching himself along the way, before making a pair of shorts for his own benefit in the mid-nineties. By Dumont’s own admission, no-one saw either, but they did pave the way for one of the great feature debuts of recent times.

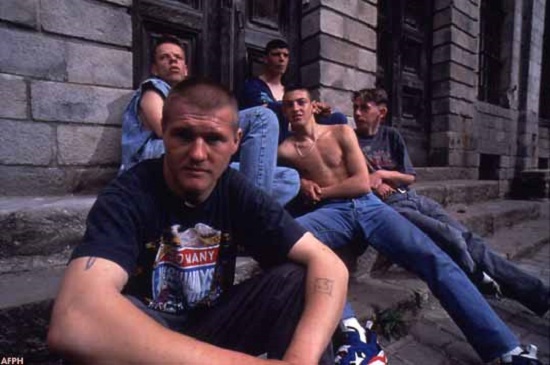

First exposure to La Vie de Jésus is a strange sensation, akin to watching a piece of outsider art. Its story – that of teenage boredom in a provincial town – is a familiar one, but the manner in which it communicates that story is incredibly off-kilter, or at least when placed against our expectations. Dumont was (and still is) dead set against the norms of commercial French cinema: the emphasis on dialogue; the heavy, moralising tone. His teenagers are not an eloquent bunch – thus cancelling out the former – and so their existence is captured in a more urgent, primal form. The film stares right at them, fascinated by their rawness, but not in that uneasy way typified by Larry Clark’s movies. Dumont has cited Pier Paolo Pasolini as an influence and you can see a similar approach to capturing the face and the human body – because that’s where the immediacy lies. Their shared use of non-professional actors only aids the task thanks to the lack of performance. In lead actor David Douche we find someone who is visibly shy of the camera and never once makes eye-contact, as it were. As such there’s no playing up, no showing off, and yet still it relentlessly stares back.

It’s almost tempting to label Dumont’s actors as unwilling participants such is their onscreen demeanour. They don’t feel like actors in the conventional sense of the word, yet the air of mundanity and ordinariness they bring is central to the end results. La Vie de Jésus wants to witness them just being and that’s exactly what it does: through the long takes, that stare, the emphasis on the physical and the ‘non-performances’. As viewers we are drawn into looking beyond the simple means of entertainment – those of storytelling and character arcs – and instead into a sense of these characters’ existence. The title, of course, has religious connotations, inspired by Ernest Renan’s 1863 book of the same name. The French philosopher sought to view and document the life of Christ as you would any other historical figure, shorn of the supernatural and the fantastical, to arrive at the human behind the myth. In Dumont’s hands this translates into viewing Douche’s character, Freddy, as a modern day representation. Not in terms of telling the well-known story, but rather as a means of addressing the essentials: love, death, pain, suffering, the humanity and the baser elements. And he can only achieve this through this highly intense style. It may not always translate into the easiest of viewings, yet the overall effect is mesmerizing.

In some respects, Dumont has been remaking the same film ever since. His second feature, L’Humanité, was set in the same small town and told in much the same manner albeit within the framework of a police procedural. Genre expectations can have an odd effect and so it was that this work, in particular, split viewers down the middle. The decision to make its inspector protagonist a childlike figure with heightened emotions and a seemingly stunted IQ was a particularly maddening choice, rendering the central murder mystery almost ridiculous. Similarly, Dumont’s desire to play on ambiguities can only frustrate those looking for easy solutions. Despite these perversities, there were some remarkable moments within, captivating enough to compete with any misgivings.

Twentynine Palms relocated to the US and the environs of the American road movie for an “experimental horror”. The shift from Dumont’s native French Flanders to the Mojave Desert proved surprisingly easeful, its empty spaces perfectly susceptible to long takes and periods of silence. Here the ineloquent teenagers of La Vie de Jésus were replaced by a young couple, one Russian and the other American. Unable to speak each other’s language they communicate through a mutual grasp of basic French or, more commonly, a kind of brute physicality that eventually overspills into violence. Interestingly Dumont unwittingly broke his own rule and cast a professional actor in one of the lead roles (Yakaterina Golubeva, who had previously worked with Claire Denis and Leos Carax among others), but still achieved a suitably – and typically – intense end result. The ‘making of’ documentary that accompanies the UK DVD of the film reveals she broke a stuntman’s nose during one sequence and also shows co-star David Wissak on highly combative form with his director. I’d like to imagine this is typical of Dumont’s sets, chockfull of emotion, possibly with him goading from the side-lines.

(Last year saw the release of Sibérie, a ‘documentary’ by former girlfriend Joana Preiss. She and Dumont filmed each other on mini DV cameras over the course of a train journey, effectively charting the breakdown of their relationship, though some fiction was ‘introduced’. During the many terse exchanges between the two, Dumont refers to himself as a “manipulator”.)

Follow-up Flanders returned to the hometown of La Vie de Jésus, borrowing one of its supporting players for the lead role. Familiar territory prompted a familiar feel, but – four features in – little had dulled its raw edge. Scenes of rural life and everyday boredom maintain the spark of the earlier films but make up only part of the picture. This was Dumont’s war film, shipping out a handful of its key characters to the Middle East for an unidentified conflict and all manner of brutality. After the final act of Twentynine Palms (not to mention moments in both preceding features) we should come to expect outbursts of violence, and yet the scenes of rape, torture, castration and execution feel somewhat over-egged and lack the immediacy of the quieter moments. Indeed, subsequent works, whilst still containing extremities, seem to have taken a step back.

Hadewijch even picked up a ‘12’ certificate from the BBFC, a real surprise for a director who deals so directly with sex and violence that it’s hard to imagine his films without them. There again, this particular effort felt a tad more mainstream thanks to its somewhat warmer – though far from untroubled – protagonist and an emphasis on dialogue. (Dumont’s use of an extreme widescreen frame was also reduced, thus bringing us closer to the screen and the characters therein.) Dealing with religious fanaticism and fundamentalism, it should go without saying that there was still plenty of room for confrontational material, but the dull force of La Vie de Jésus had been tweaked and toned into something ultimately less impactful. Dumont is at his best when handling a blunt instrument, it would appear.

Which is why Hors Satan feels like a genuine return to form. If L’Humanité is Dumont’s police thriller, Twentynine Palms his horror movie and Flanders his war film, then this is Dumont’s serial killer pic. Such terminology is essentially correct, but only reveals so much. So whilst Hors Satan’s central couple of David Dewaele (a holdover from Hadewijch) and Alexandra Lemâtre may outwardly resemble, for example, Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek in Terrence Malick’s Badlands, that isn’t the entire story. For starters everything is stripped back so that it’s almost bare, from the dialogue to the backstory. Dumont also plays up the ambiguities, or rather creates a situation where every action can appear ambiguous thanks to the lack of solid detail. In the case of L’Humanité that often proved frustrating. But here, thanks to fewer associations with genre norms, it frees the director to head off into less certain territory. Connections are made with Pasolini’s Theorem or Dennis Potter’s Brimstone and Treacle, with Dewaele’s character held up as some kind of mysterious stranger, both Christ-like and, as the title suggests, Satanic. Much like La Vie de Jésus, Dumont’s approach ensures that we get right inside of him.

Hors Satan and La Vie de Jésus feel very much like a pair; the various mutations of style and storyline ultimately bringing Dumont to similar territory. Yet no sooner has he returned than he jumps off in an entirely new direction. Camille Claudel 1915, which premiered at the Berlin Film Festival earlier this year (and therefore means we can probably expect it over here in 2015), turns its attentions to the past, a historical figure and, perhaps most unexpected of all, casts an instantly recognisable face, namely Juliette Binoche, in its lead role. The critical consensus at Berlin was split right down the middle, so at least one thing hasn’t changed…

Hors Satan is released on DVD by New Wave films this week