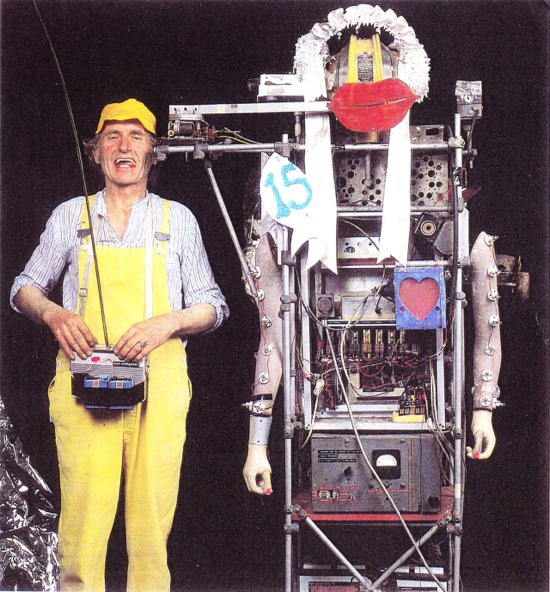

Songs about filmmakers have a tendency to be thin on the ground. Mogwai named a track after Stanley Kubrick on their third EP, while Stereolab took inspiration from Stan Brakhage. John Cassavetes has come off better than most thanks to namechecks by Fugazi, Le Tigre and The Hold Steady. But the list is a short one and to delve further is to delve into some real obscurities. Consequently songs about filmmakers which also happen to feature their subject – surely the highest of honours – are even rarer, though two do spring to mind. In 1994 Sparks invited Tsui Hark, one of the key figures in the Hong Kong film industry, to provide the spoken word accompaniment to a tribute track: "I’m Tsui Hark. I’ve made several films. I’ve won several awards for my films." Twenty five years earlier Ashley Hutchings wrote about his pal Bruce Lacey for a track on Fairport Convention’s second album, What We Did On Our Holidays. ‘Mr Lacey’ not only featured the man himself but also his homemade robots whirring away in-between the verses. It also included the telling final lyric: "It’s true no one here understands now/But maybe someday they’ll catch up with you."

I strongly suspect that Lacey doesn’t quite register with readers in the same way as a Kubrick or a Cassavetes. Even Brakhage and Tsui, while perhaps not familiar to a mainstream audience, are major names in their respective fields. Yet Lacey is different and finds himself still languishing in obscurity; nothing more than a footnote in the annals of cult-ish British filmmaking. Hutchings was right, we still don’t understand, but perhaps 2012 – some sixty years since Lacey first got himself involved with a movie camera – will finally see the rest of us catch up. This summer brings all manner of goodies, including a brand new documentary from Jeremy Deller and Nick Abrahams, various screenings at BFI Southbank, an exhibition at the Camden Arts Centre and The Lacey Rituals: Films By Bruce Lacey (And Friends): a typically weighty, two-disc endeavour from the British Film Institute that is chock full of his eccentric delights.

Lacey was a product of art school and National Service, part of the generation that would redefine the landscape of British humour during the 1950s and ’60s. As a satirist and self-confessed silly bugger he was anti-establishment and against any notions of empire, yet firmly tied to his culture’s past through a deep love of music hall and vaudeville. Indeed, it could be said that Lacey never left his childhood, forever demonstrating a youthful energy and curiosity across the decades as his work slowly shifted and mutated into areas of fresh interest. Starting out as a sculptor he has also been a performer, a filmmaker, a composer, a musician, an artist in myriad senses of the word, and plenty more besides. Approaching the man without any prior knowledge can be a daunting task, though paths can be plotted through those years.

If Lacey is ringing the tiniest of bells and yet you’re struggling to place him, the most likely source is his brief cameo in the second Beatles movie, Help! (1965). He played George Harrison’s gardener, the one who tends to his indoor lawn with a mower constructed from joke shop teeth. Such an appearance was typical for Lacey, often with one of these self-made contraptions to hand, in both features and on television. Cult oddities such as Adult Fun (1972) and Smashing Time (1967, tagline: ‘Two Girls Go Stark Mod!’) had a space for the man and his inventions, while Associated-Rediffusion Television gave him regular employment as a props man. His designs – and occasionally himself – earned themselves supporting role in various post-Goons sketch shows for the likes of Peter Sellers and Spike Milligan. At the same time they would also find guest spots on the BBC, turning up in an episode of Not Only… But Also alongside Pete ‘n’ Dud or subject to an entire Monitor documentary helmed by Ken Russell. Lacey was rubbing shoulders with the key players of the time, but rarely allowed his own solo slot or starring vehicle. Instead, he had to do so on the periphery.

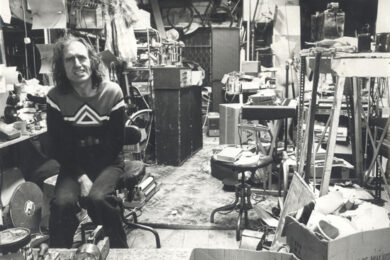

Fittingly, the first efforts with a camera were amateur ventures dating back to Lacey’s time at the Hornsey School of Art. These were playful and ambitious films, celebrated within their own circles (including favourable coverage in Amateur Cine World and its ilk) but effectively hidden from general view. Only now can we get a glimpse, thanks to the BFI DVD and its attendant Southbank screenings, and it’s interesting to see how their moods and methods would remain constant throughout Lacey’s cinematic endeavours. The various shorts to which he has put his name remain defiantly lo-fi and retain that home-constructed aesthetic. Oftentimes they are simple sketches or mere records/reconstructions of his various ‘happenings’ and installations – in other words, not quite fully formed. Ideas excite Lacey and these are what he communicates, whether it be a slice of politically motivated satire or something a little more artistically inclined.

This waywardness – flitting between the humorous and the serious – poses the question as to whether Lacey was more comedian or artist. Certainly, many of the television appearances and various feature film cameos position him in the former category; another Brit eccentric to rank alongside his more famous co-stars. The earliest of the shorts do much the same too, especially those made in collaboration with anarchic musical comedy duo the Alberts and/or future Roobarb/Henry’s Cat animator Bob Godfrey. They possess the same spirit and silliness as many of the comic acts that were to come into their own during the Sixties. The overall tone seems to predict both Monty Python’s Flying Circus and the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band. Neil Innes and Rodney Slater, then students of the Royal College of Art, even pop up in The Flying Alberts (1965) to cement the connection. Other co-stars and collaborators during this period included John Wells and William Rushton of Private Eye, fellow British comedy everyman Graham Stark, Ivor Cutler and glamour photographer George Harrison Marks.

Perhaps there’s something about Lacey’s appearance too which inherently lends itself to the comedic. Blessed with a gangly frame, long but thinning hair and a false set of top front teeth, he seems a natural fit for the onscreen absurdities. Such a figure and features make perfect sense within the comic context – opposite Spike Milligan, say, or playing The Beatles’ gardener – and yet they were just as readily employed in Lacey’s more experimental works. In the late ’60s he embarked on the Human Behaviour films, a series of works which refused to take for granted everyday activities such as taking a bath, having a shave or going to the toilet. With mainstream filmmakers more concerned with action, great drama and romance, where were the cinematic records of such things in case the human race were to die out? Thus Lacey, his second wife Jill Bruce and their three children were employed to ensure this information existed for other civilisations to discover.

Of course, such an idea, once again, has its comic potential. Yet Lacey’s execution – while playful – is entirely serious. Indeed, the reference points and kinships created by these works relate more to genuine experimental filmmakers than they do the British satirical set of the time. The Lacey Rituals (1973), a day-in-the-life collection of commonplace activities- "all the things you never saw in The Waltons" – recalls Ian Breakwell’s Continuous Diary series; the strong ties to Lacey’s family life bring to mind Stan Brakhage’s most personal films (Cat’s Cradle, say, or Window Water Baby Moving); and the frank sexuality of Double Exposure (1975) and its use of superimpositions create a connection with Carolee Schneemann’s Fuses. The artistic credentials were upped further by Lacey’s involvement in the 1965 International Poetry Incarnation at the Royal Albert Hall plus exhibitions at the ICA and the Serpentine Gallery. The latter involved the entire family – now dubbed the Community Art Group – in an extension of the Human Behaviour films. Later, Lacey would develop an interest in New Age mythologies and the ancient sites of Britain, creating and performing his own rituals at festivals around the country (prior to their corporate takeover) and making landscape films on Super 8. He even dabbled in video art.

All the while, there have been the robots and the crackpot inventions. Lacey never stopped being a sculptor, forever enthralled by junk shop discoveries and the now rather quaint space age futurism of his creations. They’ve toured galleries, featured in the movies, put in an appearance at an Ideal Home Exhibition, even competed in – and won! – the annual Alternative Miss World contest that Andrew Logan has been putting on since the early ’70s. Strangest of all was one of the robots acting as Lacey’s best man when he married Jill in 1967. In doing so was he being serious or irreverent, or maybe just taking the piss? The answer is probably a mixture of all three, which also happens to perfectly sum up the man himself.

The Lacey Rituals: Films By Bruce Lacey (And Friends) is released next Monday July 23 by the BFI. The double-disc package includes Jeremy Deller and Nick Abrahams’ documentary The Bruce Lacey Experience. The latter also screens at an exhibition of the same name at Camden Arts Centre until September 16, co-curated by Deller and art historian Professor David Alan Mellor.