How nations choose to remember themselves on film is always problematic, in the documentary as much as the fictional form. Access to the difficult or dirty aspects of a country’s life, such as war and industry, is controlled and defined by the state or big business. This is very much in the background of the mind when watching the two films that British Sea Power have created soundtracks for at the British Film Institute tonight, namely Andrei Ujica’s 1999 documentary Out Of The Present (previous discussed by the Quietus at its debut outing at the CERN laboratory in Geneva) and From The Sea To The Land Beyond, a new feature edited together by Penny Woolcock using footage taken from the BFI archive.

British Sea Power have long explored thorny issues of national memory and history by holding up mirrors to the past to question the present. This has, of course, led to them being falsely accused of nostalgia, dreaming of days when happiness could be found in a pomade wave and a stolen gasp, or breath of ale behind a creosoted NAAFI hut. This is a reductive view, and one that these musicians do not deserve, as they abundantly prove once again at the Southbank.

The group are at their best when everything is implied, and their music acts as illumination. This is why their score to Robert Flaherty’s Man Of Aran (1934) was so powerful. Even without the moving image, it stands up as a deeply evocative piece of music that contains all the quiet heroism against hardship of those islanders who hunted the basking shark decades ago.

Out Of The Present is still very much a work in progress, perhaps in part because it sees British Sea Power boldly going in new directions that might be hard to reproduce live. It’s a brave move for them to introduce elements of four/four techno, but also a commendable one, replacing the original soundtrack which, the closing credits inform us, comprised Frank Sinatra, Tanita Tikaram’s ‘Twist In My Sobriety’ and "computer incantations for world peace". BSP’s pushing of their own envelope shows great promise of being among their finest work to date, matching the documentary’s own subject matter: cosmonauts aboard Mir watch the earth slip beneath them as the Soviet Union crumbles, wiling away their time goofing around and conducting experiments. The experimentation of British Sea Power seems to be in a similar spirit to that of the filmmakers, who we see stood atop their hotel, flimsy aerial wires in hand, making contact and then conversing with the cosmonauts up on the space station. This spirit illuminates things and places as much as people and life.

The band’s evolving score is well judged. The sound of technology, like the roar of the rocket, becomes part of the music, a techno movement emerging during the Mir docking sequence. There’s an excellent doomy hum and lurid piano as the Soyuz rocket, with Union Flag and hammer and sickle side by side, glides slowly and surreally over a most Soviet-looking area of bleak scrub to the launch site. In more thoughtful sections they allow the poetry of the film to sing for itself – be that explosions of superheated candle wax which revolve and burn in weightlessness, or the giant, collapsed silver balloon of a failed experiment that twists and flails in the nothingness outside Mir.

Compared to the forward-thinking nature of Out Of The Present, From The Sea To The Land Beyond could be problematic. The inherent limitations of the British Film Institute’s archive mean that much had to be done with footage which has already been fairly well used over the years. What’s more, there’s a preset narrative at play: imperial Britain dominates seas plentiful with fish, then participates in two World Wars, followed by decline, most keenly felt in docks and shipbuilding, before the double-edged revival of consumerism and redevelopment of London’s Docklands. Look! A man windsurfs there now, past the old cranes that sit like the skeletal remains of a once mighty beast along the water’s edge.

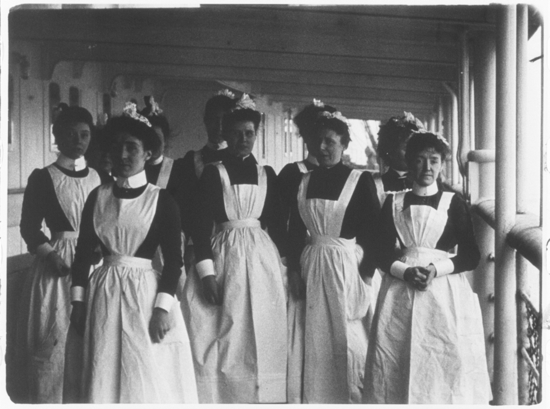

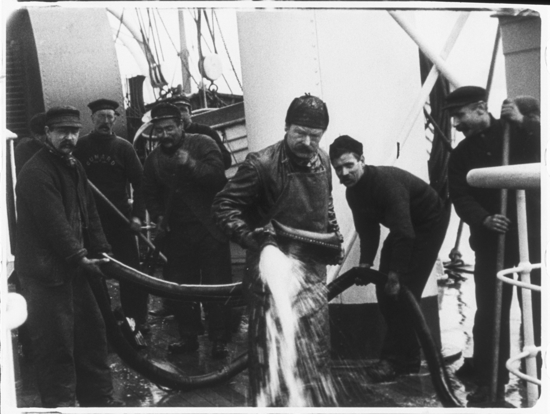

The earliest footage is taken from Blackpool at the start of the 20th century. There’s a carnival procession with flower-adorned floats and a placard about the suffragettes. Fellows conduct a swimming race in evening wear complete with top hats, watched by packed boats of spectators in similarly fine attire. Nobody wears life jackets. I bet nobody drowned. A sign reads ‘Palmistry & Phrenology’. Stout men work a ship’s telegraph. Others with appalling dentistry grin on a tugboat, while women repair nets and gut, salt and pack herring, or dangle off the sides of cliffs in order to collect eggs.

Nevertheless, director Penny Woolcock manages to make much of this rich visual tapestry. To her credit, she rescues it from becoming a mere exercise in nostalgia. This much is evident early on. The audience laughs at two sturdy men sat on a log, doing their utmost to whack each other with sandbags and dislodge their opponent into the ditch below. So far, so slapstick… until you notice that they wear battledress, and the footage cuts to women filling shells, then an aircraft flying over a battleship, which explodes. Sandbags would soon be needed for darker purposes.

British Sea Power’s accompaniment is made up of reworked versions of moments from their back catalogue, including elements of tracks like ‘Carrion’ ("Always, always, always the sea/Brilliantine mortality") and ‘The Great Skua’ along with some new material – the trumpet blast of ‘Radio Goddard’ is especially promising. As with Out Of The Present, BSP make great use of nature’s white noise, such as the violence of chains as a ship heads down the slipway. A conflagration in a derelict dock becomes a vessel’s horn, part of which the melody returns. During footage of Luftwaffe bombing raids on shipping in the Channel, the six musicians – sat watching the screen with their backs to the audience – unleash a multi-instrumental roar that escalates as the footage advances to D-Day via ack-ack, searchlights and families sat around the fire, waiting for news. Woolcock says that she found this appropriately "terrifying".

Contemporary culture’s great mistake is to confuse things of great beauty with things that are nice or simple and unthreatening – cute animals or the endless ‘LOL’ of the internet’s washed-out visual nothing (the Instagrammed present is going to look very strange to future students of the past). These have taken precedence over the unusual elements of life and the awkward past that require a few more seconds of grey matter exertion in order to yield up a truth. Yet these deeper matters are what British Sea Power understand so well, and what they so effectively illustrate with the music that accompanies these films. It’s hard to imagine another group operating today who could soundtrack footage of both astronaut Helen Sharman floating weightless in a pink nightgown through a space station that’s now atomised into nothing and a girl twirling high on a girder while beating a tambourine – or less dignified contemporary visitors to Blackpool, drunk-puking against a storm – with such intelligent poignancy.

The Sheffield Doc/Fest performance of British Sea Power soundtracking From The Sea To The Land Beyond can be viewed online at The Space.