It has been 15 years since the last true Scorsese film.

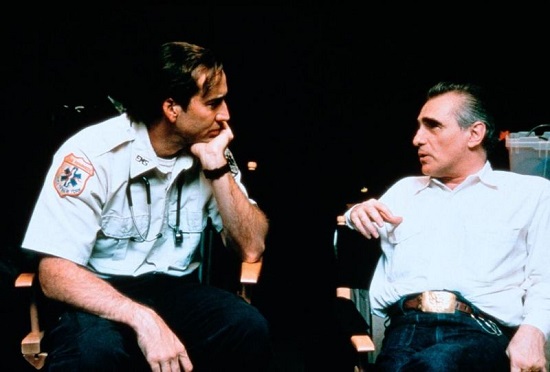

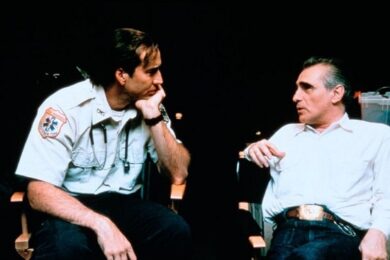

This week marks the fifteenth anniversary since the release of Bringing Out The Dead (1999), Scorsese’s drastically underrated and comparatively unknown noirish dramedy. More to the point, it is his last film to pack the punch and verve with that we have come to associate the veteran director. Written by Paul Schrader (Taxi Driver) and starring Nicolas Cage in one of his more immediately affecting roles, Bringing Out The Dead is shaped around Frank Pierce, a broken and beaten paramedic who struggles to hold onto his sanity amidst a steady onslaught of soul-sapping night shifts and fatalities. Washed up, alcoholic and semi-deranged, his sole objective is to save someone and save himself in the process. Such dusky subject matter has long been a fruitful stomping ground for Scorsese, and he shoots it with an intense style and dynamism here.

Bringing Out The Dead was a categorical box-office flop. Produced on a budget of $55 million, it earned just shy of $17 million worldwide. Nevertheless, the film garnered critical approval, with seminal critic Roger Ebert awarding it a perfect four stars. Applauding the film’s uncompromising potency he said, “To look at "Bringing Out The Dead"–to look, indeed, at almost any Scorsese film–is to be reminded that film can touch us urgently and deeply.” Ebert outlines what, exactly, film – as an art form – should seek to do, and how Scorsese in this film, and a great many before it, achieves that.

Bringing Out The Dead is astounding in its impact. Scorsese works like an unhinged puppet master, as he coerces his principal character further and further towards the abyss. Deftly encouraging the aesthetics and mise-en-scène to obfuscate Frank’s world, Scorsese creates in New York City an unrelenting cycle of misery and death. Nothing is straightforward – Frank is desperately hopeless, but wants nothing more than to provide hope to others. Instead he is a ferryman, transporting the dead to the other side, rather than saving the living. Every single decision made by Scorsese compounds this narrative journey, making the horror all the more immediate, the bleakness all the more enervating.

The flashing blues and reds of the ambulance lights bleed into the surrounding nighthawk environment, throwing ghostly shadows across Cage’s face. The wailing squawks of Van Morrison’s ‘T.B. Sheets’ – an artfully selected leitmotif – syncs with the cacophony of the siren. Scorsese is thoughtful in his utilisation of this device; deploying it here and there at opportune moments, the yawping harmonica penetrating each scene. Yet, it is the more subtle implementations of this song that have the most resounding effects. There are moments, when Frank is driving the ambulance, city lights flickering across his face, and Morrison howling on, that the tone shifts slightly, the sounds muffle, and the song bleeds from the non-diegetic world into the diegetic. The song becomes a part of Frank’s universe, thus signifying the fragmented reality of the film.

Despite being set in a very specific area of New York at a very specific time, Scorsese effectively deconstructs period and place into ethereal webs that cling to Frank Pierce, effectively aiding in further disrupting his disposition. This is perhaps most evident in the unearthly aesthetics of the hospital – Our Lady Of Misery. Time and place are fluid in this location – doctors and nurses are constantly working regardless of date and time; bodies are piled up in the corridors; every bed full, the same patients and the same cases repeatedly roll through their doors. It is a Sisyphean nightmare. These qualities are intensified by the visual construction of the hospital – a typically Scorsesian choice, but a signifier of the otherworldly nature that haunts the film’s very core. The green, ectoplasmic hue that clings to the hospital walls and saturates the fluorescent lighting has enormous capacity to further distort reality. A spectral ether flows through the physical bounds of the building. The place becomes purgatorial, as if the very strands of reality have been dismantled and reconstructed time and time again, ultimately becoming a cyclic theatre for Frank to navigate.

It is these touches – particular the use of lighting, colour and leitmotif – combined with the subject matter of a broken man haphazardly negotiating with a dangerous city that are so prominent in Scorsese’s earlier, more classic works and so woefully absent in his films of the last fifteen years. One only has to look at the scene in Mean Streets in which Robert De Niro’s character enters into the bar to see the how far back these techniques stretch – the camera floats deliberately through the crowd, the image is purposefully soaked in red and ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’ blasts over the top. These three elements all work in conjunction to not simply introduce De Niro, but to introduce Scorsese as a director of great power and impact.

Further to this point, there are direct lines that arc between Bringing Out The Dead and Taxi Driver – both penned by Schrader. Each narrative follows a man staggering back and forth across the thin demarcation between sanity and insanity- an internal landscape that is in no small part reflected by the perilous urban environment. Both glide up the stygian New York streets observing sickness and death, witnessing first-hand the afflictions that plague the city streets. Both Bickle and Pierce, in their own way, endeavour to cure New York of its ills and both ultimately succeed at this, if only in a microcosmic sense. This narrative trope has long been prominent throughout Scorsese’s career and to an extent remains intact today. However, it has not been seen in such succinct and harrowing terms since Bringing Out The Dead.

Scorsese no doubt has an extensive and varied filmography. After all, between 1980 and 1988, he moved seamlessly from Raging Bull (1980) stopping off at After Hours (1985) before arriving at The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). His interests have always been far-reaching. Nonetheless, it is becoming increasingly apparent that we are now at the fag end of Scorsese’s career, and while those preferences remain eclectic, the driving forces behind them have undeniably waned. He has, in recent interviews, stated that he likely does not have many films left in him. It is, then, all the more painful that his films since the turn of the century have left so much to be desired. There has been an undeniable shift since then in both his thematic predilections and stylistic decisions. Looking at, say, the entertaining but overwrought exultation of the nascent years of his home town in Gangs Of New York (2002), or Hugo (2011), his often charming and tender tribute to the origins of motion picture, this shift in focus is all the more clear. Whereas once, Scorsese’s fixation lay with troubled individuals struggling to stay afloat in a broken and dangerous city, his aim, now, seems to be to inspect and eulogise an assembly of dead relics that he holds dear.

His psychological thriller, Shutter Island (2010), emulates the stylings of classic film noir in its aesthetic, staging, and even narrative. Whilst Scorsese’s technical aptitude is unquestionable, here, his fascination with cinematic titans Otto Preminger and Bernard Herrmann is so undeniable and apparent that it in fact takes centre stage.

The Departed (2006)is in itself a rather more flaccid affair, even more so than many of his more recent works. Granted, it is certainly a watchable picture, even if it is a nigh on carbon copy of Hong Kong thriller Infernal Affairs (2002). However, that is in no small part due to its pandering to some of his more populist traits as laid out in Goodfellas (1990) and Casino (1995). Outside of those quasi self-referential aspects, there is little to be applauded. The film is so patently unsubtle in its conveyance of its central themes that it borders on the absurd, to the point that, by the final scene in which we see a rat scurrying across Matt Damon’s balcony – in case you’d somehow managed to miss the constellation of other references to rats and infiltration that permeate the film – you’re left with a feeling that Scorsese, despite winning an Oscar, may have just phoned this one in.

Scorsese has remarked that, at his age and with his familial priorities, cinematic experimentation no longer takes as great a precedence in his life as it once did. That, however, doesn’t necessarily ring true. After all, can one really say that Hugo – a CGI-laden 3D children’s film with a didactic breakdown of the birth of cinema – has no sense of cinematic endeavour? Really though, any envelope that may have been pushed in this film, has been inched away from the heady altitudes of Scorsese’s seminal films, towards rather more limiting and saccharine depths. Indeed, much of Hugo is arguably text book, from the opening scene over a Parisian cityscape to the final long take, and the multitude of filmmaking allusions that are scattered throughout. And perhaps that is the problem. It is all too ordinary, too textbook, and let’s face it, too boring.

His most recent offering is perhaps evidence enough that any essence and experimentation Scorsese may once have had has all but turned to ash. The Wolf Of Wall Street (2012) – despite its utterly superfluous run time – is an entertaining romp through the boom and bombast of the New York Stock Exchange. Whilst it still manages to showcase a number of adroit directorial manoeuvres, it is utterly devoid of any notable substance, any of the hard-hitting psycho-social analysis and character deconstruction that made his films so bold and unflinching in the first place. Rather, what we are left with is a superficial story about an amoral banker with a predilection for coke and hookers who, at times, manages to present himself in a half way charismatic manner. It is a far cry indeed from those urgent and forceful punches that Scorsese has delivered time and time again throughout his stalwart career.

With his upcoming production, Silence, certainly one of his last films we are likely to see, can we expect something of a return to form from the veteran director? It is certainly doubtful that he will retreat to the more familiar stylistic waters of say Taxi Driver or even Raging Bull. However, given the storyline – a 17th Century Portuguese missionary who attempts to bring Christianity to Japan – Scorsese may well return to the territories he once trod when making the beautiful and episodic – if often difficult – Kundun (1997). As electrifying as that may be, given his recent form and the all-star cast attached to Silence, it is quite unlikely that he will retrace those steps to any particularly exciting degree.

Even the best falter, at times. Even Ali got knocked down. And yes, Scorsese too. But yet, in spite of his ostensible faults in recent years, his prolonged history of cinematic enterprise and storytelling with the ability shake, rattle and rile on an immediate and primal level speaks for itself. That is what Scorsese does in Bringing Out The Dead; he doesn’t pander or pussyfoot, he throws all caution to the wind and turns up something truly electrifying. Even if he has not done that since, just think of De Niro, standing atop the pool table in Mean Streets, flailing a pool cue, lashing out at the world. Even after 15 years of disappointment, that is Scorsese, that is his legacy. Even now, viewing after viewing, Bringing Out The Dead, Mean Streets, really any of his seminal works have the unrelenting power to be mad and captivating and utterly impossible to watch without a dropped jaw and a sensation in the pit of your stomach that burns and broils long after you’ve finished watching.