Let me show you the world in my eyes

This is a film which, like the band whose following it documents, is more compelling than you might perhaps expect. Depeche Mode svengali and Mute label founder Daniel Miller commissioned visual artists Jeremy Deller and co-director Nicholas Abrahams to make a documentary about the band’s fanbase. There was probably hope on the label’s part of projecting Depeche Mode back to their country of origin in contrasting light, to show the remarkable effect of their global popularity outside the UK. As Deller points out “they’re famous here, but they’re not really respected. [Mute] wanted a film that would appeal to fans but also to people who hadn’t really thought about the band”.

The resulting film succeeds not merely as a marketing tool but also as a fascinating ethnographic study of a diverse, global audience, brought together here in an attempt to discover how and why they could be unified by their strange passion for one motley crew of rather diffident Basildon rejects.

How hard it is for me to shake the disease

Some kind of fall from grace with the UK’s critical cognoscenti occurred during the fertile New Pop/Indie boom of the 1980s for any pop group who appeared to be a little too earnest in their take on the world — a good example would be Matt Johnson’s The The, initially championed by the music press but whose melodious handwringing in the face of a perceived Western moral decay eventually came to be viewed as risible. One-time labelmates Depeche Mode (briefly on Some Bizzare prior to Miller’s stewardship) breathed some of the same righteous air. Helped and hindered by Martin Gore’s occasionally gauche sloganeering — “people are people so why should it be you and I should get along so awfully” — they have never quite shaken off a view of them as just another 80s band punching synthetically above its weight.

The often bitter, sometimes gloomy atmosphere of their songcraft belied an obtuse intelligence jostling for position with all the other rabid stylists to be seen on an average airing of Top of the Pops in 1984. They embraced industrial sampling and a visual aesthetic vaguely redolent of socialist iconography, blended with hints of transgressive leather and chains — a public image closer to acts from the industrial underground, such as DAF, than anyone likely to be seen on TOTP. Lyrically, too, they mounted a spiky challenge to the conventional mores of Western life, with its illusory “great reward” of marital bliss (“come on and lay with me, come on and lie to me”) financial greed (“everything counts in large amounts”), an increasingly disinforming, media-driven celebrity culture (“In black townships fires blaze, prospects better premier says . . . Princess Di is wearing a new dress”) and the notion of a secure national identity. They were also sensitive to the ironies of operating within the ferociously free market of the music industry, dubbing their publishing company Grabbing Hands.

All this was backgrounded by a peculiar vulnerability that perhaps could only have been formed in the conurbations of provincial Essex. Amusingly, as The Posters Came From The Walls gets going, a Basildon resident who witnessed the rise of the band at first hand tells how “you could be beaten up for wearing eyeliner. Not the women . . . but blokes.” The core dynamic of this 30-year-old band, forced to mature in public, has helped them survive and endure a lot more since then, with Dave Gahan (whose own weaknesses have been well-documented) as the frontman shield and Andrew Fletcher as crutch to Martin Gore’s fragile muse.

Perhaps being earnest is something the coddled, media-savvy consumers of British society at large have forgotten the importance of. As one enthusiastic Russian teenage Depechist (a styling suggestively invoked by another Soviet fan) puts it, “what other music has the sound of forks, railway ties and scissors? It’s a complete original”. It was with the fans from an oppressed Eastern Europe that DM’s radical pop chimed first and loudest.

Strangelove, strange highs and strange lows

The 90s saw the band move away from the quasi-political concept of Music For The Masses towards a pseudo-religiosity, offering their audience a kind of congregational sanctuary. Spiritual secularism is nothing new in pop music, but the explicit play with religion (sparking controversy with one marketing ruse providing a hotline number to a "Personal Jesus") revealed the band as highly complicit in developing a certain view of themselves. When I point this out to Deller he responds animatedly: “Oh yeah, absolutely, Martin Gore consciously flirts with all that and pushes people’s buttons. He knows what’s gonna get people excited and he knows religion is one of those things, [though] not necessarily in Britain”.

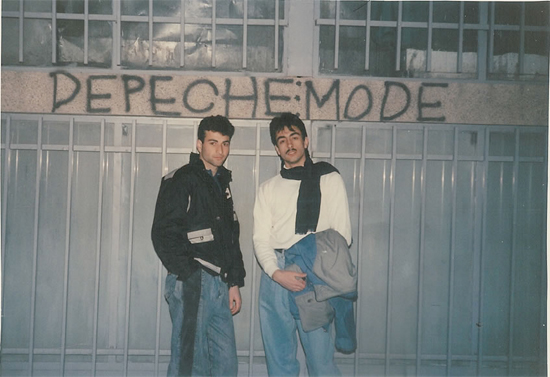

This music nourished an emergent youth culture throughout Europe’s Eastern Bloc, recently freed from its former dictatorships in a wave of revolution, which yearned for transcendence from the spiritual and material privations of communism. Says Deller: “We’d heard about their following in Eastern Europe and Russia and wanted to see if it was true. And it was. Their story fits in with historical and social change”.

Further footage of the band’s devotional following is found across the globe from Sao Paolo (“Catholic fans go beserk when they see all that religious imagery”) to Tehran (where simply liking the band, much like in the Soviet Bloc nations, was practically criminal), via various United States (Depeche as bling accoutrement; rioting fans; an apparently middle class American, whose brass band interprets DM songs, declaring them “alternative before the word became a marketing tool”) all the way back to a formerly homeless Londoner who claims to have found redemption and purpose in the shared experience of a DM concert. And perhaps the British aren’t as universally post-faith and secular a society as we think just yet: one segment shows a Christian clergyman enthusing about young goths coming to sing their favourite songs dressed up “in their gear into what is after all a Gothic building”.

Deller explains how DM tours, now rapturously attended in Eastern Europe (and South America, though not Iran for some time, one imagines), were once prohibited in many of these countries. Their art has nearly always toiled somewhere near the interface between freedom and oppression, with servants and strangelovers still languishing under their masters on the track ‘Chains’, which opens their latest LP Sounds of the Universe. Perhaps their appeal to the disenfranchised and the marginal (there is also a notable gay subtext running through the documentary) lies in their acknowledgment of pain as a necessary part of existence.

Indeed, some of the Eastern European youth who describe DM as the “music of freedom” might beware of what they wish for — instead of piling into town squares and venues to celebrate ‘Dave Day’ (Gahan’s birthday, it would seem, coincides with an important Russian state holiday), they could soon be milling around whooping outside generic nightclubs like Fabric, mourning the split of Oasis and eagerly anticipating the return of Robbie Williams, spoon-fed by a PR machinery every bit as faceless as the cultural police of the communist era.

Faith and Devotion

“There are many bands you could make a film like this about, but would it be an interesting film?” asks Deller, who also tells me that there is not a little miffedness within DM’s ranks at the way those other post-punk stadium slayers U2 hijacked their image by courting Anton Corbijn to recreate 101 as Rattle & Hum at a similarly critical, quantum leap career phase. “But with U2 everything is spelled out”, he continues, “this is good this is bad. There’s a bit more ambiguity with Depeche”. If any echo can be found amongst contemporaries, perhaps The Smiths’ acerbic/empathetic take on life, love and everything is closer than the proselytizing Bono, with Morrissey also having a fanatical following in Mexico and US Hispanic communities. In any case, and without wanting to start any blasphemous rumours, arguably all any of these hugely successful artists now face is their status as articles of faith, preaching to the converted, reflected by that ultimate accolade of the capitalist world — steady sales.

The filmmakers decided to keep the band’s profile almost entirely in absentia, a move curiously resonant with DM’s games of self-deification. And any directorial voice is kept silent — this is very much the fans’ film. Given the often bizarre displays of fan mania, I wondered if they feared they might appear to be mocking their subjects as they made a cult of themselves for the camera. “The fans muck around with the imagery of the band, they know they’re odd, they’re not deluded. When we first showed the film in London everyone was laughing for the first five minutes — they thought it was a comedy. Then they calmed down and realised they didn’t have to laugh. The pressure was off them to find it funny”. Which surely says more about us than them.

Visit the film’s website for details of forthcoming screenings and more information

The Posters Came From The Walls is being screened at this weekend’s Branchage Film Festival in Jersey. To find out more, visit the Branchage website