There aren’t many filmmakers that have the patience of Richard Linklater. But patience is only part of what makes his films so magical; Linklater’s main strength is his extraordinary vision. The fact that a collaborative undertaking such as Boyhood was seen out to its end is a breathtaking example of that vision, during which the Texan director would routinely reassemble his cast over a span of twelve years, filming the growth of not just his characters but his actors and actresses. But would such lofty ambition bear fruit? Who has time to do this in today’s filmmaking climate?

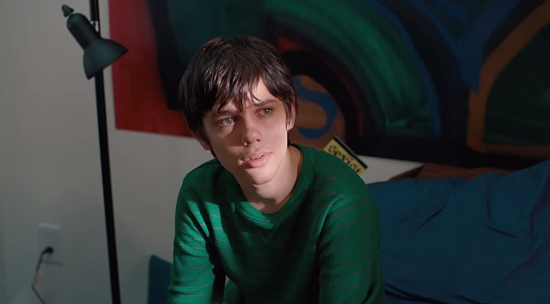

Mason (Ellar Coltrane) is a young boy, and eventually a young man, who life is piercingly similar to many of our own. He may be at the core of each of the movie’s 166 minutes, but his mother and father – played by Patricia Arquette and Ethan Hawke – are the forces that will mould him on his journey from age six to age eighteen, while his sister Samantha (Linklater’s own daughter, Lorelei) grows alongside him, reflecting his own mental and physical development. Mason grapples with the everyday, while also overcoming terrible stepdads, peer pressure, and first love. There is no story here – only life, pushed ever forward by the unstoppable flow of time.

And in life, things happen one after the other, whereas in drama, things happen because of one another. And at no point does Boyhood feel like an ordinary drama, despite its no-frills look at suburban existence. Events tumble one over the other, and vast stretches of time pass by without anything resembling a conventional plot. As a result, none of it feels like it was designed on paper first. Nothing seems to happen, rather, it escalates. Being privy to these character’s lives in such a close capacity, so like our own, can be overwhelming at times, and observations of the different relationships Mason makes hit hard. Cleverly leading us through this immense timespan, and getting us to relate to these people (‘people’ simply seems more natural than the term ‘characters’ here) is the inclusion of all the throwaway minutiae that doesn’t really matter, but that marks our time on the planet so vividly. Perfectly cued pop culture references are embedded through the movie like breadcrumbs, leading a trail for Mason toward maturity. In a particularly funny scene, father and son debate the possibility of future Star Wars movies. Half-forgotten hits and sleeper smashes play in the background, both diegetically and non-diegetically. The Hives’ ‘Hate to Say I Told You So’ overscores mischief in Mason’s early years, while ‘Deep Blue’ sits aside the first stirrings of romance that act as the full-stop in his transition from boy to man.

Time may be these people’s enemy, but it’s Linklater’s best friend; throughout his career, the director has toyed with time on his own terms. Dazed And Confused was a one-night snapshot of the last vestiges of high school life; Waking Life stretched and pulled time out of shape; the Before… trilogy considers the temporal nature of love. Boyhood, by those measures, is his magnum opus, his ultimate exploration of the human condition and its umbilical connection to the ticking of the clock. But Linklater shows us that time isn’t necessarily all destructive; entropy can also be inspiring. Before our very eyes, it’s not just Mason who grows up, but Coltrane too – something that’s usually an entirely private aspect of a person’s life. We see the formation of someone who could be a stone-cold movie star, if he so decided. Similarly, Arquette has never been better, and Hawke is the fun, but not entirely useful, dad you’ve always (sort of) wanted. It’s an entirely singular cinematic experience to watch both facial hair and wrinkles develop, for real, during the course of a movie, but the experience is never gimmicky despite the allure of its formal premise. Although Linklater essentially shot a short film every year, Boyhood never once smacks of a series of vignettes; it’s a seamless piece of art. Any time you may feel slightly taken out of the movie by a growth spurt or a new hairstyle, which Mason and his sister naturally have a proclivity toward during the twelve years, it feels instead like being reunited with a niece, nephew, or friend’s kid that you haven’t seen in a while. They grow up so fast, and there’s nothing you can do to stop it. You could label Boyhood an extended snapshot, a high-reaching attempt to capture the messiness of those formative years, but the film never wants to freeze anything. It’s a celebration of life slipping through your fingers.

Boyhood represents why we go to see films, and why we make them. Linklater’s long game demonstrates that our capacity for awe is not something that needs to be bound to the physical passage of time; inside our heads, time doesn’t mean anything. And similarly, it doesn’t mean anything on the big screen. It’s this very understanding that makes Boyhood a masterpiece, and affirms its director as the best in America today, working at the height of his powers. The film’s complexities are eternal, like the consequences of every decision we’ll make over the next twelve, twenty, and thirty years of our lives, but are all held together by a devastatingly simple conceit. Boyhood begins with the six year-old Mason lying on the grass outside his school, staring into a blue sky peppered with pretty clouds. It’s an idyllic image, one of purity and simplicity; he can lie down and stare up at the stratosphere as long as he likes, because, unlike the adults in his life, he has time. But that time is slowly robbed from him as he becomes an adult himself. The clouds Mason watches will disappear forever, but he’ll experience more beautiful things during his time on Earth. the film ends with gaze cast not to the sky, but into the eyes of another human being.

Boyhood is in cinemas from today