Creating a life in New York City in the late 1970s was no easy feat. After a nationwide economic recession and the middle class’ exodus to suburbia, the city was left to fester as unemployment and crime reached historic highs. The city was abandoned by the government and its people, but a small, artistic community flourished amidst it all. Circling around the likes of legendary arts venues the Mudd Club and CBGB, a world of collaborative and democratic punk bohemia was born. Here, alongside No-Wave filmmaking greats Amos Poe, Eric Mitchell, and Vivienne Dick, filmmaker and film producer Sara Driver got her start.

Though known primarily for her producing work with long-term partner Jim Jarmusch, Driver’s own films have spanned multiple genres and formats, received critical acclaim by renowned film journal Cahiers du Cinéma, and have since solidified her spot as a key figure in late twentieth century independent American filmmaking.

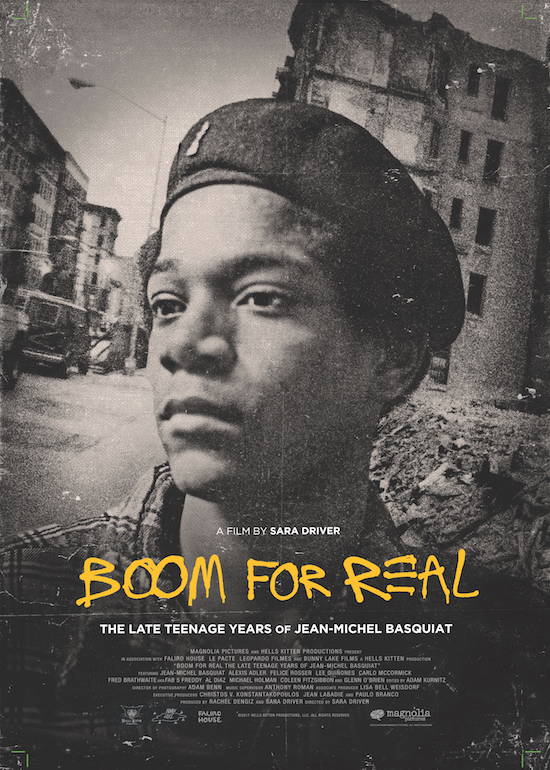

From her debut short film You Are Not I (1981) through to her latest feature When Pigs Fly (1993), she’s privileged the perspective of characters who have had distinctive points of view or unique imaginative abilities. As she returns to filmmaking in 2018 with Boom For Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Driver revives this tendency by focusing on the famed yet enigmatic artist with an uncontainable imagination and distinct artistic perspective that has influenced the art world to this day. As she lands in London for the UK release of the film, we sat down with the director to find out more.

How did you make your way to New York and become part of the downtown scene?

Sara Driver: My dad worked in New York City, so it was an early fascination for me and I knew I would live there one day. When I got out of college and I moved into the city, I started working in theatre. I had written a play about Zelda Fitzgerald, and people would say, “That’s very cinematic.” And I said, “What does that mean?” From there, I decided to go to NYU film school. The school itself was in the epicentre of the East Village. It was a really fine film program where they only took around 150 students. You had to be invited back each year, so each year the classes got smaller, which wasn’t so great because people began competing with one another, when it’s really a collaborative medium.

Who were some of your early friends and collaborators in the city at the time?

I worked in the equipment room with Spike Lee and Ernie Dickerson, which is where I met Jim Jarmusch, Tom DiCillo, and Howard Brookner. When I first met Jim, he asked, “Would you produce Permanent Vacation (1980) for me? I need to get fifteen locations for free.” That’s when I first came to producing, and that was a really cool way to collaborate. Producing is creative as well; you have to try to make things happen for the director, when often you really don’t have the money to make it happen. You have to figure out clever ways. That was one of my strongest early collaborations. But of course, I tried to start a band too, like everybody else.

What was the band called?

The members of the band were Judy Wong and Barbara Klar, so we were Driver-Wong-Klar! It didn’t last that long; we weren’t really great musicians, but we tried. And Richie Edson, who’s one of the leads in Stranger than Paradise gave me my drum lessons. I think we were all doing something creative. We were all painting, and you’d go over to someone’s house and start drawing.

Is that how you met Jean-Michel Basquiat?

I don’t really remember the first time I met Jean, but, it may have been that incident in the film [where he spontaneously approached Sara in the street to gift her a flower]. He was just a kid like all of us. He was just around. Everybody would see each other at clubs or on the street. I remember we were shooting Permanent Vacation, and he was sleeping on John Lurie’s floor, and we had to keep moving him out of the way of the camera. He would just sort of raise his head like the Dormouse in Alice in Wonderland.

Did he help out at all?

No, no – he was sleeping! Well, you know he would have a long night the day before, tagging around the city.

He seems a bit mischievous too, both from your experiences and the experiences of those featured in the film. Is there a certain way you wanted to portray Jean-Michel in Boom for Real?

If you look at the pictures that Alexis Adler took of him, where he has Silly Putty on his nose, and he was acting out all of these funny scenarios, like putting the TV in the refrigerator – you could see it. He was very bright. But, you know, a lot of people would get fed up with him too. He did have a bad habit of painting on everyone’s floors and walls, and Alexis Adler was the only one who really loved that. Glenn O’Brien also was really important to Jean-Michel. Glenn O’Brien was an editor at Interview magazine and he pretty much spotted Jean early on. I have an outtake of Glenn saying, “As soon as he put a crayon on paper, I knew he was something special.”

As far as I know, Glenn and Alexis are the only people who kept a body of his work from that time. Most people just threw it away. When I saw Alexis and what she had, I knew that this was a window into him as an early artist, because you get all the signs of what’s in his later works. And it was also a window into this very particular time in New York in the late 1970s too. After 1981 when Reagan became president, it all changed.

What kind of access to archival footage were you given?

We didn’t have a lot of money to make this film, and archives can be very expensive, and because I was a part of this whole community, people gave to me very generously. They wanted to see the story told by somebody who was part of it.

It’s surprising that there wasn’t significant funding behind this project considering the resurgence of interest in the period.

People said, “There are already Basquiat films.” But this film is so different than those other films. Art can be very reflective of our time, and I think Jean was a little bit of a prophet. His work is so relevant now because of what he was living through at the time as a young black man. He was crying out to say, “Wake up. Look at what’s going on.” I think that’s why people feel him, and feel his paintings. There’s an energy and a vibrancy.

Why do you think the backdrop of a crumbling, bankrupted city served as the perfect space for an artistic movement like this?

You didn’t need very much money to live, so you could spend a lot of time making your art. I worked in a Xerox shop with Kim Gordon, and it was the only job I could really have when we were on hiatus from Stranger Than Paradise.

And Xeroxing as a craft was so important for zines at the time, band posters, and movie promotion.

Yeah, exactly. All these great artists used to come in and do color and black and white Xerox. We were playing, but working.

Along those lines of evolving craft and technology – what was the transition like from filming on Super 8 to filming on digital?

I love the quality of Super 8. The actual tactile feeling of Super 8 and film is so beautiful. If I had an opportunity, I’d absolutely go back to filming on it. I like that you can sit with an editor and see where the end of a reel is. It’s very nebulous, this digital thing. I know how to do everything on film. I know how to transfer sound on a Mag Stock – all the basic stuff. Digital changes all of the time, and you also have to have a very educated editor.

Who did you make this film for?

I wanted to convey that there’s strength in community. Kids will come up to me after they’ve seen the film, and they’ll ask, “How do we start this kind of community? How can we have this kind of exchange?” I want to instigate it, because I want that in my world. I want artists coming together. I tell them about this great art fair that I love in New York called Spring/Break. It started in this abandoned Catholic School in Little Italy, they cleaned the whole place up and had 150 curators and more than 500 young artists. There was a line of people five blocks long, and there had been no publicity. There’s so much energy. But most importantly, it sets up a situation where artists can meet each other and be in a real community.

Do you think art school and film school is still necessary, or should people just seek out opportunities like this?

Everybody’s different, but I’m all for the punk attitude of just going out and doing it. Of just trying to find your way.

Boom For Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat, directed by Sara Driver, is at UK cinemas now