If you have a racist grandparent, embarrassingly prone to public spewing of the vilest slurs, followed by the defensive protestation that they’re just telling the truth and saying what everyone’s really thinking, well, cinema knows how you feel.

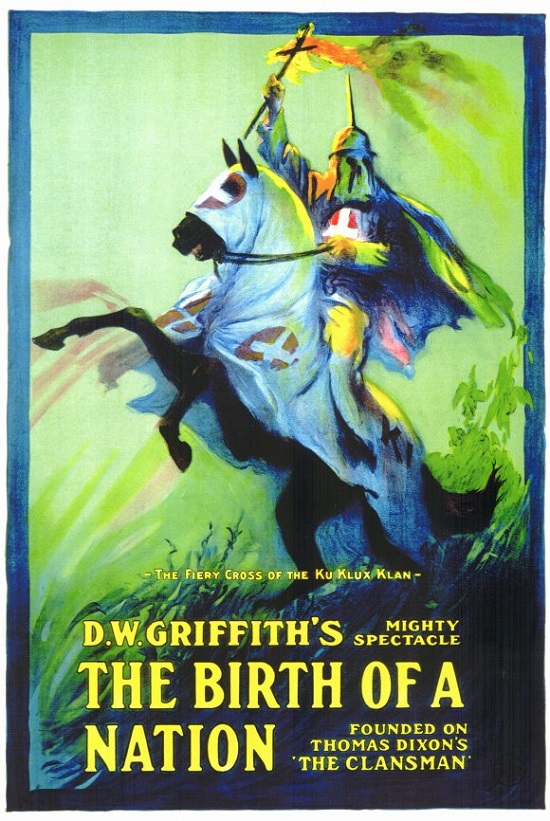

The Birth Of A Nation, the 1915 masterpiece (one is tempted to say ‘meisterwerk’) of D.W. Griffith, also signals the birth of the feature film, and the blockbuster, as we know them. It is a huge event in the history of cinema, and a significant one in history as a whole, as well as – in a strange and ugly fashion – in the history of history.

To take those matters one at a time: into an age of film still dominated by one and two-reelers came, if not the first epic, certainly the one that revolutionised the American industry by its impact. Three hours long, and full of ideas and techniques which swiftly became and in many cases have remained standard, The Birth Of A Nation is one of those great earthquakes that level an art-form and cause it to be built anew. Not only did it transform the movies; by doing so, it helped to transform the dominant culture of the last and (thus far, despite all claims to the contrary) this century: American popular culture. Meaning its aftershocks are felt even now. And in retelling the most pivotal episode in America’s history since its founding, The Birth Of A Nation changed the way America perceived its own past. Very much for the worse.

It is impossible to watch it now without these matters foremost in mind. You could no more look at those marvels of cinematic skill and invention, Olympia and Triumph Of The Will, without having the thought, “…yeah, but, Hitler…” scrolling across your consciousness like a news ticker. Equally, you cannot help but recognise its prodigious achievements, even as you recoil from its imagery and message.

The Birth Of A Nation’s subject is the American Civil War and, crucially, the subsequent reconstruction of the South. Griffith’s father, ‘Roaring Jake’ (no, really), was a Confederate colonel. Among the extras on this new two-disc restoration from Eureka is a 1930 interview in which Griffith proudly describes his mother sewing costumes for the Ku Klux Klan. That is the key to this film: it is encapsulated by its celebration of the Klan as a noble secret army, an “Invisible Empire”, founded from “a mere instinct of self-preservation,” and with the, ahem, purest of motives, by those battling against forces which sought to “put the white South under the heel of the black South.” It encompasses every dreadful implication that belief in such a view could entail.

Those last two quotations, by the way, are from Woodrow Wilson, that great liberal statesman, president at the time of the film’s release, and an ardent segregationist. He did not directly endorse the film, as has long been erroneously claimed, although it became the first feature to be screened at the White House. His quotes precede it. But he is thus cited in its titles, and again by Griffith in that 1930 interview which prefaced a new version. (Although The Birth Of A Nation had been shown almost continuously until then.)

What Wilson did effectively endorse, in advance, was the film’s view of the reconstruction; a portrait so grotesque, the titles featured a weaselly disclaimer that it did “not mean to reflect on any race or people of today.” What effect Wilson’s statements had in lending credibility to that view, one cannot quantify. But Griffith’s repeated appeal to them suggests he relied heavily upon them..

The Birth Of A Nation opens with the canard of the Civil War as a struggle undertaken solely in defence of states’ rights by the South, defying the oppressive North in a doomed but righteous cause. Y’know: that whole, “It wasn’t that we were trying to maintain slavery for its own sake, no, sir; just those dad-burned Yankees had no right saying we shouldn’t,” line. The South in question is a familiar one, represented by a wealthy antebellum household divided between happy slaves and “kindly master[s]”, where “life runs in a quaintly way that is soon to be no more.” It’s all pickaninnies, puppies, and a Mammy who resembles Dame Edna Everage in blackface. A footnote, here, but a telling one: the principal black parts, such as they are, are played by obviously white actors, which in retrospect lends a symbolic resonance to the business, and serves as continual reminder of who is telling the story.

So far, so familiar. Those tropes are distasteful but archaic enough to stomach. Where The Birth Of A Nation becomes truly repugnant is in the post-war scenes. Austin Stoneman, a radical fanatic of a congressman, wields supreme power after the assassination of Lincoln (here portrayed as “the Great Heart” and a friend to the South, despite that unfortunate matter of waging war upon it). Just how radical a fanatic is he? Well, he believes in the self-evidently intolerable notion that, “blacks shall be raised to full equality with the whites.” Thus driven, he stirs up the South’s blacks, who duly terrorise the helpless white population. At first by trying to shake their hands, insisting on sharing the pavement, and similar outrages, which naturally make any Southern gentleman’s blood boil. But soon, inevitably, by seizing control of the legislature, attempting to despoil innocent white women, torturing and murdering honest, loyal servants, and so on.

All of which sets up the arrival of the Klan as a force of deliverance, often literally so; until, by the end of the film, come election day, the blacks emerge from their hovels to vote, only to confront a line of mounted Klansmen, and return suitably cowed whence they came. The rightful order is restored.

If this sounds difficult to sit through, it is, but not just for its utter wrongness. It is, after all, a three-hour silent film, and what was dramatically compelling in 1915 is not always so now. It is bound to drag. Yet, in addition to its longueurs, it is full of remarkable things. It has scenes of profound tenderness, genuine excitement, undeniable poignancy and knife-edge suspense. Its purpose may be polemical, but in narrative structure it is a melodramatic potboiler in the theatrical style on which early cinema so often drew (it was based on a popular play, The Clansman, by Thomas Dixon Jr, a Baptist minister and white supremacist), and Griffith’s handling of it is masterful. As are his battlefield depictions, which – aside from the overblown gallantry of the close-ups – were perhaps unrivalled in their apparent verisimilitude until the opening of Saving Private Ryan.

The accompanying 1993 documentary by Russell Merritt and David Shepard on the making of the film is instructive on this and several other points – such as the way Griffith relied upon photographs and illustrated reportage to recreate the battles, and the pivotal political episodes in the North; but for events in the post-war South turned to caricatures and propaganda, which is what his own work in turn became. Indeed, if there has been a more effective and far-reaching individual work of American propaganda than The Birth Of A Nation, I find myself unable to think what it is.

It was not universally well received, it should be stressed. Although successful on an unprecedented scale, the film was widely denounced as deceitful, hateful and malicious – all of which it is – and Griffith himself was sufficiently stung by those criticisms to take a very different turn with his next film, Intolerance. But the damage was done. Its release was followed by a mass revival of the suddenly respectable KKK, and its account of the reconstruction was for decades accepted at face value, making life much easier for those historians who sought to promote it.

Still, there is only so much indignation one can, or should, summon over a century-old film’s depiction of events that took place another fifty years before. The values of the present should not distort an understanding of the past. But that is the truly terrible thing about The Birth Of A Nation: far from being consigned to the dustbin of history, its core themes at this moment define great swathes of American political and cultural life. It is difficult, in the context of the George Zimmerman trial, and the return of Jim Crow via ‘voter fraud’ laws, and a continual barrage of similar evidence, not to think its values are, for many Americans, the values of the present. It prefigures and coalesces almost every element of contemporary reactionary attitudes in the US.

There’s the absolute, dogmatic, self-pitying sense of victimisation that accompanies any erosion of privilege among those who possess it, or the gaining of civil rights by those who formerly had none. The conviction that these changes result not from social forces, or a struggle for justice, but from powerful, deluded figures driven by manias to inflict them upon ordinary, decent folk who want none of them. The illogical assumption that equality is, or ever could be, a limited commodity, and if one group rises from the depths to claim it, another once above them must fall below. The narcissistic invocation of honesty, decency, integrity and common sense as virtues that define those opposed to such reform.

Among the few notable differences: The Birth Of A Nation is all but devoid of religiosity – bar a final scene which appears tacked on for form’s sake. And it applauds the disarming of blacks as a decisive moment in the turning back of the barbarian tide – a thorny problem, that would make, for Second Amendment advocates caught between the twin evils of gun control and scary minorities legally equipped with firearms.

There is, however, one bright aspect. The Birth Of A Nation suggests that reactionaries used to be very good indeed at popular art. They’re almost invariably rotten at it now. For that and many other reasons, it would be disingenuous to suggest there’s been no cultural progress at all. The half of America that abhors this sort of thing includes almost every creative individual and institution worth a damn.

Still, it is a bleak moment when the realisation settles upon you that this film, this demented, puffed-up travesty of history and race, far from being anachronistic, is perhaps as close as one can get to a panoramic view inside the collective mind of today’s American Right. As you watch Silas Lynch, Stoneman’s fiendish "Mulatto” apprentice, who slips from the control of his master to wreak horror upon the worthy white folk of South Carolina, empowered by the “nigra” vote, you remember this is how today’s US Right views Barack Obama: as a dusky thing of vengeful nightmare, an uppity ogre propelled into power by the disaster that is an enfranchised underclass, desiring nothing more than the ruin of the whites and the placing of his own kind in dominion over them. How they must long for the same resolution The Birth Of A Nation provides: a return to the halcyon days when the lower races Knew Their Place.

Lynch is an extraordinary creation, a cinematic villain of authentic heft and menace. Both he and the film’s principle villainess, Stoneman’s housekeeper turned paramour, who through Stoneman plots the debasement of whites and the exaltation of blacks, are “mulattos” – that is, of mixed race, and thus the worst creatures of all, for they represent the unspeakable crime of miscegenation. The whites, to a man and woman, are honourable, upright or heroic – with the exception of Stoneman, who is (as his name implies) an immovable dupe. The blacks are simple, subservient and cheerfully devoted to their natural superiors, cartoon monkeys in hats, all but; dumb and harmless until misled into permitting their innate savagery free reign. But the sinister, scheming “mulattos”, with their white intelligence made dangerous by their inherant black brutality, must rank among the most overtly slanderous cinema portrayals of any race this side of Jews in the films of the Third Reich; diabolical darkies who will stop at nothing to subjugate the white man and slake their foul desires on his women.

Has The Birth Of A Nation itself any claim to have aided the perpetuation of the mindset displayed within it into the present day? Impossible to say. It may have done, but the chain of influence is too long and kinked to make a certain case for that. Here’s what we can be sure of, though. Usually, when one says of a work that it is as relevant today as it was in its own time, one intends it as a compliment. In the case of this magnificent, fascinating and appalling film, its current relevance is undeniable. But that’s not a tribute to The Birth of a Nation. It’s an indictment of the times in which America lives.

The Birth Of A Nation is available now on DVD and Blu-ray from Eureka’s Masters Of Cinema Series