All Eyez On Me might be showing in multiplexes all across the country, but expectations will be low amongst anyone who’s seen more than a handful of biopics. Death and taxes might be life’s only certainties, but they’re closely run by the probability the next biographical music film you watch will be execrable, predictable, and in some cases, doggerel. The Tupac Shakur film comes hot on the heels of Straight Outta Compton, a watchable if overlong account of the rise to infamy of N.W.A in the early 90s. Following on from its surprise success, there are a predictable glut of hip hop-related movies being discussed, including a Russell Simmons life story and Welcome to Death Row, a sequel of sorts to the F. Gary Gray-directed box office smash.

Full disclosure: I’ll not be rushing to see All Eyez On Me, and that’s not just because of the terrible reviews it’s been receiving. With an aggregate score of 38 on Metacritic thus far, the New York Times says scenes shot by director Benny Boom are executed with a “dismal stolidness” while the movie “plods along with a ‘and then this happened’ dutifulness”.

“Man I watched the 2Pac film, that was some bullshit,” said rapper and actor 50 Cent on his Instagram recently. “Catch that shit on a firestick, trust me.”

Despite the criticism by critics and high profile Makaveli fans (as well as the rapper’s ex-girlfriend, Jada Pinkett Smith), the film managed to reap a respectable $27m for its opening weekend in the US; while only doing around half of the business Straight Outta Compton did, it fared far better than had been widely anticipated. Not bad for a film that follows the chronological made-for-TV formula that suffuses the genre these days, with few or any attempts to shake things up (if only with the charitable intention of trying to keep audiences awake).

If you’re wondering if you’ve seen it all before then chances are you have. The actor Jamal Woolard, who played Biggie Smalls in 2009’s Notorious, is recast in All Eyez On Me as the same character, a role Woolard carried off well originally despite being 10 years older than the 24 years Christopher Wallace was when he was assassinated. Now an entire generation older, this timeworn tribute act, dusted off and brought into the daylight once again, seems to epitomise the lack of imagination that goes into biographical movies in general. Biggie and Tupac’s star-crossed lives were intertwined – certainly retrospectively that case has been made umpteen times – though neither film by all accounts has much – if anything – to add.

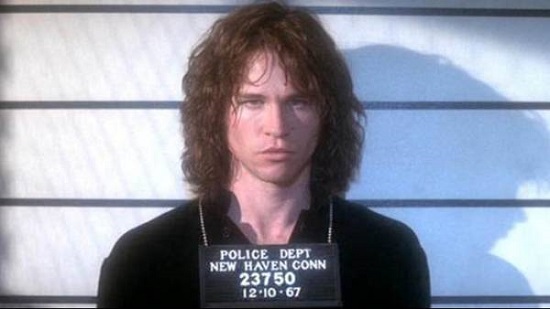

In his 1992 book Bio/Pics: How Hollywood Constructed Public History, George F. Custen complained that biopics “since the 1960s [seem] to have faded away to a minor form. Today, it is seen most frequently on cable channels, in rare contemporary form like The Doors (1991) or Sweet Dreams (1985), or in intriguing transmutations of made-for-TV movies.”

The Doors, for all its faults, is at least a preposterously vaudevillian rendition of a life on screen, seen through the lens of Hollywood’s favourite conspiracy theorist, Oliver Stone (if you want to see a truly awful movie based on a conspiracy theory by the way, then watch the 2005 Stephen Woolley-directed Stoned about the death of Brian Jones). Jim Morrison’s surviving bandmates certainly weren’t happy about the way the Doors singer was depicted up on the big screen. “I looked in the man’s eyes and I saw something wrong there,” said keyboard player Ray Manzarek about Oliver Stone. “Something’s wrong with this guy. The Doors movie is a pack of lies.”

The late film critic Roger Ebert once said “those who seek the truth about a man from the film of his life might as well seek it from his loving grandmother”, and for those closest to the main protagonist, the on screen misrepresentation – as they see it – can be very painful.

“Oliver Stone did a terrible job,” added Manzarek, who died in 2013. “But it sure was wild. It was a wild movie, and a lot of people liked the wildness of the movie; it’s wild, but it’s not psychedelic. It was not about Jim Morrison. It was about Jimbo Morrison, the drunk. God, where was the sensitive poet and the funny guy? The guy that I knew was not on that screen. That was not my friend. I don’t know who that guy was.”

The problem for biopic makers is that they’re encumbered with faithfully recreating our memories, but our perceptions of events can wildly vary. From family to fans, bandmates to the bloke doing the merch, our perspectives will be inconsistent. Following events sequentially also leads to clumsy dialogue that signposts where the story has to head next. Kyle Maclachlan’s Ray Manzarek telling Val Kilmer’s Jimbo Morrison on Venice Beach, “let’s get a rock ‘n’ roll band together and make a million bucks”, instantly springs to mind. Even a gritty attempt at realism like Alex Cox’s Sid and Nancy came in for some flack because Nancy, played by Chloe Webb, just wasn’t ghastly enough.

One way around this is to make it up, like Django, the recent French movie starring Reda Kateb as the three-fingered giant of gypsy jazz, adapted from a semi-fictional novel Folles De Django by Alexis Salatko about the Belgian-born Romani guitarist’s wartime experiences. The film also stars Cécile de France as “a beautiful and evidently fictional French woman, Louise de Klerk,” said Peter Bradshaw in a review for The Guardian from the Berlin Film Festival in February. France plays “Django’s groupie-lover and resistance liaison agent, setting up insurgencies and escapes while remaining sexually available to the Nazis… of course Louise is destined to be vengefully abused by a chilling Nazi.”

Bradshaw’s barely concealed contempt does rather prompt the question so why bother? Taking the facts and twisting them beyond recognition is another way to make a movie more interesting – what The Buddy Holly Story director Steve Rash and executive producer Ed Cohen called “dramatic license”. A Rolling Stone article from 1978 tackles the myriad liberties taken with Holly’s life story, which left exasperated former Cricket Jerry Allison complaining, “it’s really a tinsel-town movie. Everybody thinks it’s true — that’s the shame.”

Better that directors like Rash embellish the truth than the remaining band or estate of a deceased musician take control, invariably consolidating the hagiography that’s already out there in the world with no risks taken and no awkward moments alluded to. One suspects the forthcoming Freddie Mercury biopic, out in 2018 and ruled over with an iron fist by Brian May, will throw up few surprises, and will unlikely mention Sun City either. If it follows The Karen Carpenter Story route (executively produced by Richard Carpenter), then one day it’ll make fine Sunday afternoon viewing, but in the meantime it will feel like an opportunity missed.

Of course, the flipside to not being an officially sanctioned version of the truth is that you don’t get the music, which in the case of Jimi: All Is By My Side made a dreadful film much worse, though on the more imaginative Backbeat – about the life and death of Stuart Sutcliffe – it meant assembling the “Backbeat Band” with Thurston Moore, Greg Dulli and Dave Grohl (and producer Don Was) to record many of the standards The Beatles would have played when they were in Hamburg. Backbeat also succeeds because the story is more offbeat and lesser known, which works for 24 Hour Party People too – a film with a great soundtrack, given Joy Division, New Order and the Happy Mondays are all represented in the film. In fact, Joy Division come off well in a normally unforgiving genre, with the story of Ian Curtis beautifully handled by Anton Corbijn in Control. As a pop video maker, Corbijn had invaluable inside information about the music industry which many directors don’t, and his innate creative vision beautifully shot in black and white is more art house than your common-or-garden biopic made for TV.

Walk the Line wasn’t made for TV but it feels like it. It might have won five Oscars but it’s more a wholesome prison than Folsom Prison, with a storyline about redemption and being saved from drug addiction by country music and Jesus – the whole thing feels overly simplistic and mildly patronising. The aforementioned The Karen Carpenter Story – which was made for TV – isn’t a bad movie by the way, it just isn’t particularly sophisticated. This is problematic when dealing with Karen’s anorexia and Richard Carpenter’s quaalude use, which it tackles in a characteristically chintzy and melodramatic way. In fact, as the Carpenters own music becomes more mawkish and bathetic, so too does the plot.

Director Todd Haynes has done more for fucking with the conventions of the biopic than perhaps any other director. He made his own short Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story in 1987, which features the main protagonists as Barbie Dolls (amusingly eliminating the old argument about whether an actor looks like the person they’re supposed to be playing). Then in 2007’s I’m Not There, he cast five different actors including Christian Bale, Cate Blanchett and Marcus Karl Franklin as various perceived incarnations of Dylan. The idea works because where many films purport to tell us the truth, I’m Not There acknowledges that these are merely caricatures and that Dylan is an inscrutable – perhaps the most inscrutable – music icon alive who we’re unlikely to ever fully figure out. Although whether the world needed yet another film about Bob Dylan is obviously up for debate.

Biopics don’t need to completely reinvent to be enjoyable, but the cinema goer does deserve a few surprises. Joann Sfar provided them in Gainsbourg: Vie héroïque by making the whole thing cartoonish, starring puppets that represented facets of the bibulous legend’s ego. La Vie En Rose, about diminutive chanteuse Edith Piaf saw an Oscar winning performance from Marion Cotillard (the first time the Best Actress Academy Award went to a French film), although some critics suggested part of the accolade was awarded for “going ugly” a la Charlize Theron in Monster. And Michael Douglas and Matt Damon certainly surprised and titillated the prurient parts of the press in Steven Soderbergh’s Liberace story Behind The Candelabra as gay lovers, especially as Damon looks so much like one of the New York Dolls.

Speaking of lookalikes, John Cusack bore an uncanny resemblance to Michael Barrymore in the Brian Wilson biopic Love and Mercy, which was half a good film – the half without Cusack in as it happens. It wasn’t his fault particularly, the blame actually has to go to Paul Giamatti as an overbearing and grotesque approximation of Dr Eugene Landy. Giamatti’s overacting knows no bounds these days, with Dr Landy almost indistinguishable from his portrayal of N.W.A manager Jerry Heller in Straight Outta Compton.

And so to the future, and one wonders if a film about Russell Simmons – as respected as he is – will make an interesting dramatic spectacle (are movies about entrepreneurs particularly interesting)? Certainly if there are many more hip hop films to come, then you hope a few of them will do something different from the “Rocky with a mic” blueprint we’ve seen so often over the years. Eminem only slightly subverted the familiar tropes of the hip hop biopic in 8 Mile because a) 8 Mile isn’t strictly a biopic, and b) it features a poor white rapper rising out of the ghetto with his skillz, rather than a poor black rapper. Fiddy gave the same thing a go in Get Rich Or Die Tryin’ and came up wanting, though that didn’t stop him venting about All Eyez On Me.

You might think it bad form dissing a movie I haven’t actually seen, but I disagree. I’m almost certain without setting foot into a picture house that All Eyez On Me will be something of the like I’ve seen plenty of times before, and unless I can be convinced otherwise, I don’t intend to spend anymore of my life watching the reconstituted lives of others in all their two dimensional ignominy on the big screen if I can help it.