"I’m gonna fucking put you in the hospital", shouts the man regarded by his peers as the greatest drummer of all time, as he wields his walking stick to bash the nose of writer-director Jay Bulger. So begins this compelling and often hilarious documentary about the life of Ginger Baker. The sign that greets visitors to the 73-year-old’s South African ranch reads ‘Beware Of Mr Baker’. This is no joke. Baker is described as "certifiably nuts" and "a motherfucker" by fellow percussionists Stewart Copeland of The Police and The Rolling Stones’ Charlie Watts, just two of many luminaries interviewed. He is demonstrated to be both in the most stark and visceral terms.

Ginger Baker is for many a name from the past. You probably thought he was dead. Bulger did. Having by chance saw a 1970s TV programme on Baker’s journey across the Sahara by Range Rover, he mused that the "madman with red hair" at the wheel must be long gone. That said character is alive and relatively well, but remains a cantankerous, belligerent and unusually gifted musician cements his reputation as a prodigy, force of nature and bastard.

Bulger first gained access to Baker by pitching a Rolling Stone feature. The young American was blagging – he didn’t at that stage actually work for the magazine – but the completed piece did eventually make it in, kickstarting his career in the process. Bulger now wanted to tell the story again as a tribute to Baker, but this time on film. We should be grateful he did. His debut feature has already won the South By Southwest Documentary Grand Jury Award and will doubtless pick up a few more gongs.

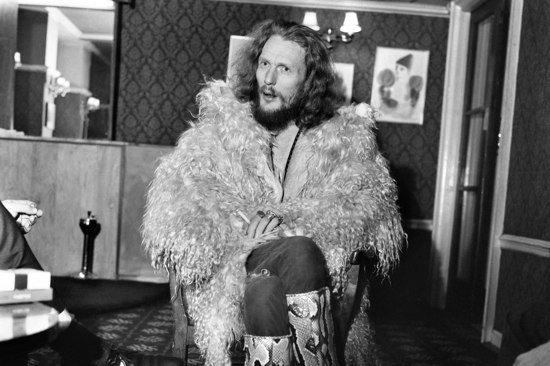

Baker is much changed. The classic image of him is stick-thin with wild red hair, cross-eyed and snaggle-toothed, often photographed midway through speaking or gesticulating, giving him a lunatic’s air. Now he’s plumper, with the red hair tamed short and grey, but the fire inside him burns fiercely. Sat back in a lounger, his feet twitching, he recalls "constantly drumming" on his desk as a kid in London. At a school dance, a drumkit was set up and his friends pushed him towards it. Instantly, he could play. "It’s a gift from god," he says. "You’ve either got it or you havn’t. I’ve got it." Bulger asks what ‘it’ is. "Timing," comes the reply. Baker explains that he can move all four limbs independently, so while he’s often regarded as one of the fastest drummers of all time, it’s because he can make the hits fall in the right places and it sounds four times faster.

Baker quickly built a reputation on the London jazz and blues scene. He also started taking heroin after meeting his hero, jazz drummer Phil Seamen, who took him back to his place to shoot up and play African records. This started in Baker a twin obsession with hellraising and Africa, represented by a series of blotchy animations linking various aspects of his life. In these he’s portrayed as a slave, rowing in a Roman galleon, or beating the tom-toms to drive the strokes of the other slaves. All the London session musicians knew one another, and Baker describes an early encounter with Mick Jagger, who was trying to build a career as a singer. "A stupid little cunt. I terrified the shit out of him," he says with glee.

Noted for playing hard and fast, using two bass drums instead of one and in a myriad of genres – from jazz to blues to African music – he effectively invented the ‘rock’ style during his stint with Cream, the power trio he founded with Eric Clapton and Jack Bruce. Baker’s fractious relationship with Bruce was, according to Clapton, the driving force behind Cream. "I was on the sidelines," says the guitarist, eventually breaking the band up because he couldn’t handle the stress.

Baker has a low opinion of the metal genre Cream are sometimes credited with spawning – he regards himself as a jazz drummer – and is offended by comparisons to the likes of Led Zeppelin’s John Bonham. "He had some technique, but couldn’t swing a sack of shit," Baker says through the perpetual cigarette, his voice so old and worn he could easily portray the bad guy in a film. Which bizarrely he did, appearing in some forgotten 1980s Hollywood B movie he describes simply as "fucking stupid". In his strange, meandering life he has lurched from fame to bankruptcy several times, on quixotic journeys to Italy, Nigeria and California, while becoming obsessed with the sport of polo – his home is a ranch for horses – and playing drums sporadically, but never losing his talent.

Apart from pots of anger Baker is largely unemotional, with a strained relationship with his three former wives and many children. Naturally, he found it impossible to be faithful for even the shortest length of time. His children fared worse, particularly his eldest son Kofi. The boy took up the drums and, aged 15, visited his bankrupt father in Italy. They rehearsed for a special concert but Kofi fell ill on the day of the performance. To get his son on stage, Ginger gave him his first line of cocaine. Once the gig was over, Baker kept the proceeds and sent the teenager back home. Kofi remains incredulous and cynical about his father but still lives in his shadow, running a Cream tribute act.

Baker’s rare emotion emerges when he connects with his drums, playing extended duets with a grown-up Kofi during bizarre polo plus jazz days in Colorado, the two men talking via their snares in a way that was impossible with words. It’s a great opportunity to make up for lost time, but Baker once again implodes, turning on his son in the most vicious way. He speaks to other drummers the same way, letting his emotional guard down only over the skins. In a drum battle with Art Blakey in the 1970s, both drummers are plunged into a state of near-ecstasy and pleasure, communicating telepathically over the drums. Many years later Baker is moved to tears remembering the recognition of his idol, Max Roach.

John Lydon, who hired Baker to play on PiL’s 1986 Album, has nothing but praise for the veteran, acknowledging his inherent difficulty but opining: "This is the price you pay for musical perfection." However, such irascibility would make Baker impossible to work with, and the offers eventually dried up. While the man is incomparable behind a drumkit, he’s an emotional cripple and has no notion of responsibility.

In a baker’s dozen of digressions, the years spent in Lagos stand out. This was where he constructed a state of the art studio with Fela Kuti, embracing the Afrobeat scene and recording local talent. At a time when bigotry was rampant in the UK, it’s to Baker’s credit that his long-held anti-racist views come out so strongly. But the political situation in Nigeria soured, and Kuti became suspicious after the drummer joined an elite polo club. Baker upped and left, leaving behind everything he had built. This introduces the delicious possibility of several years’ worth of unheard sessions, sitting in a drawer somewhere in Lagos. The documentary will do much to boost the appeal of any reissue.

Recounting these many disparate episodes, Bulger does an extraordinarily fine job of keeping the narrative cogent, bringing fantastic archive footage to life in a series of montages, and evoking the madness of its protagonist Mr Baker.