Phil Cox, director of the new documentary on Betty Davis, was in prison, puzzling over a long list of filming no-nos from “the Greta Garbo of funk”, when a crow arrived to help him. Cox had been kidnapped while on an investigative assignment in Sudan. “And there, outside my cell, every day,” he tells me, “Was this crow. I thought, Jesus, Betty’s followed me out here!”

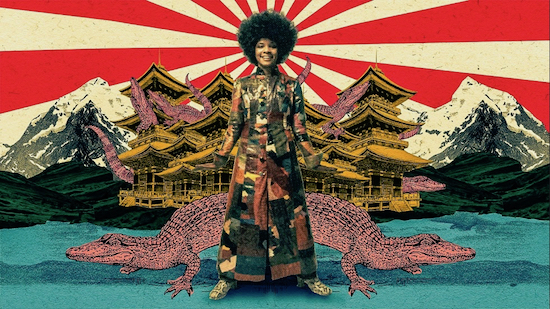

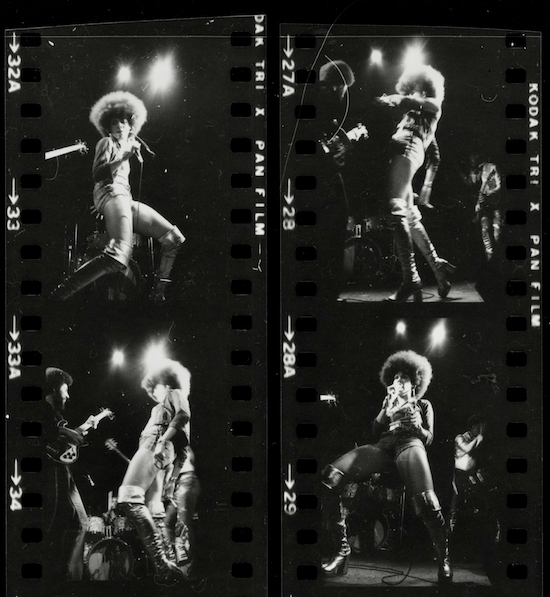

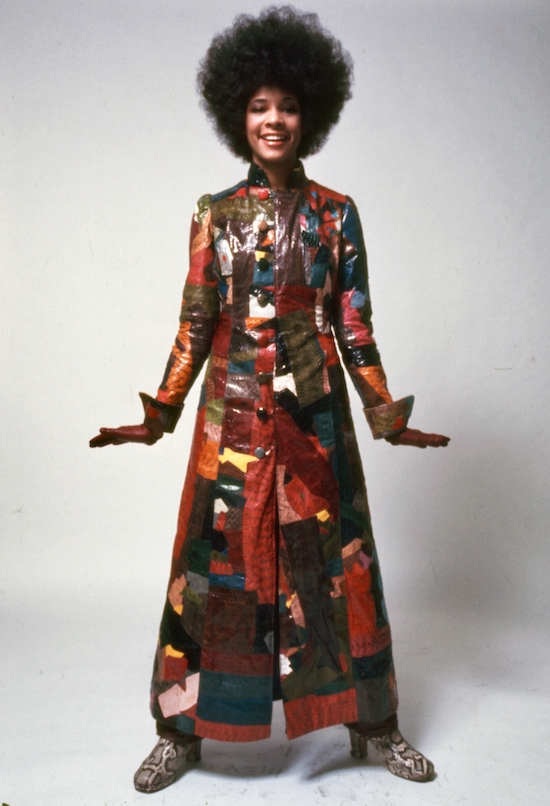

Once you hear Betty Davis’ breakout music, involuting love and pain, scavenging rock, funk, blues, afro-jazz, Spanish folk and space-disco – and see her, in the 70s, in a plunging zebra swimsuit, with raven feathers on her shoulder, Cox’s crow might well seem like a visitation. Betty had told Cox, by then, that Crow is her spirit animal. Now 72, Betty had also stipulated that he not film her face. So it is Crow who swoops and stitches a patchwork of historical documentary, collage and the only-remaining footage of Betty on stage, in ‘76, creaming in a silver bikini.

For a beautiful black songwriter, producer and bandleader who, alongside her co-conspirator, Jimi Hendrix, had birthed the freaked-out colours of 60s New York, Betty’s desire for physical absence may seem like another imprisonment. But Betty, a fashion student and model who rose from a violent marriage to an older, powerful man (Miles Davis) to become a 70s Bay Area funk-fusionist, is a mistress of myth-making. Like Bowie and Cohen before her, Betty Davis is curating her legacy. Betty is part Cherokee – and Crow, in the Native American tradition, is both the core and void of creation. Her decision to shit on Phil Cox’s film-making ambitions and their beautiful, continuing friendship – Cox is one of Betty’s few, trusted ambassadors – is Betty’s way of hurling the intrigued viewer to the core of her music and starting to make feathers fly.

We are granted glimpses of this one-time Amazon, sitting, bowed and silent, on her leather couch. Turquoise-polished fingers light incense. In a tiny white bedroom, a barely-glimpsed older woman writes, filling a foolscap A4 notebook with lyrics. This new song, ‘Two Hands’, is a lament for a lost beloved who will be met, once again. It will never be performed. Then again, who knows?

Betty’s work is being re-released. She has now met with her band Funk House and cooked rice for Erykah Badu. But initially, US networks refused to distribute Cox’s film: “They were like, ‘she’s got no name recognition, we don’t care.’ Her previous accommodation was… I don’t want to say poverty but extremely basic. I contacted a lot of people who jammed with Betty, dated her, like Eric Clapton – never mind being in the film, just to reconnect with Betty. They didn’t want to know.”

In 1973–76, Betty Davis whiplashed three stinging, swampy, fanny-wiggling groundbreaking albums, the only female songwriter to colonise the male funk sound. For her first, Betty Davis, she enlisted Sly and the Family Stone’s Greg Errico, as producer. Errico, who rifles through his bag of rehearsal tapes in the film, also drummed a silvery-sharp artillery behind Larry Graham’s skintight bass and Santana’s Neal Schon’s lubricious guitar hooks. Betty’s voice crashed a narrow-gauged track from guttural to angelic. She proposed that women could share men, same as men enjoyed mistresses (‘Your Man, My Man’). The ecstasies of casual sex (‘If I’m In Luck I Might Get Picked Up’), were backed by a street-mob of vocals from The Pointer Sisters and Sylvester. Next, commencing a run of self-produced albums, she was a cock-worshipping, turquoise-chain-wielding dominatrix (and supplicant) in ‘He Was A Big Freak’ on Betty, They Say I’m Different. Zippy beats, sweaty clavinet, tickling keyboards and cunt-farting guitar also entwined her uterine growl on Nasty Gal, unrepentantly teasing the “uptight” press for needing Betty Davis to “keep my tongue in my mouth”, while caressing the lily of dying love in the ballad ‘You and I’, written with ex-husband Miles Davis. Her fourth album, Is it Love or Desire, rescued by Light In The Attic Records, in 2009, was her artistic breakthrough into a smokier, spookier musical progression. When it was shelved, Betty Davis, according to legend, vanished.

“For a long time,” says her voice, in the film, husky-sweet as sugar-cane, “We couldn’t talk about it, Crow and I.”

What “it” may be, is never quite revealed by Cox’s sensitive, if scanty, tale of her 30-odd year disappearance. “I could only,” Cox tells me, “Use ten per cent of what I’ve come to know.” Carmine and teal animations, referencing Betty’s spiritual conversion in Japan in the 80s (when she climbed Mount Fuji, while playing at The Crocodile Club, in a little-known gig), go unexplained. Through these holes, Betty scatters crumbs – and bombs: “Voices in my head. Strange faces. Shame. My heartbeat changed.” Nobody in the film is inclined to name her confrontation with another taboo, mental illness; another suppression; more shame.

What better way to overturn shame than to embrace it? The time has come to reassess Betty Davis’ sex positivity as a revolt against patriarchal abuse that’s hugely liberating for women today.

Miles Davis turned love into shame. He beat Betty. He can be heard, on the long-missing tapes from The Columbia Years, released in 2016, taunting her: “You speak better than you sing, Betty.” Though she tried to reconcile his rejection in two songs, ‘You and I’ and the eerie, jazz-trickling, ‘When Romance Says Goodbye’, one of her finest creations on Is It Love And Desire, I discovered that he’d traumatised her over their divorce papers for years. In his own memoirs, Miles dismissed as a ‘supergroupie’ the woman who’d musically helped him birth Bitches Brew (the album was even named by Betty).

Her response was to own this trash; to pull Miles and all the dirty, beautiful, insecure bastards into the dumpster with her. She poetically proffers her cunt and arse in metaphors, from the dancefloor storming, ‘Git In There’, to inviting a ‘Lone Ranger’ to “run your fingers through my bushy hair’. It’s avant-garde advice for women, today. Being a man’s plaything, “talking trash”, is not weakness but a way to spread our cunty wings and fly into the taboo space that separates man and woman. “I’ll do anything,” she promises, in ‘Game Is My Middle Name’. On top, riding “the saddle”, or boosting a man’s ego by gripping his heels as a geisha, Betty toppled the sex game. But pitting male against female was only superficially Betty’s flight; not its glittering, hidden core. She chugged on heavy basslines into the pit of male desire, invited them to “show me your bag of tricks”, in order to heal the male psyche and resolve the gender split. If she left men (‘Nasty Girl’) hanging by their nails, she also, prophetically, begged that her lover did not “mess with my mind…” If he left her, she growls in ‘Come Take Me’, “I couldn’t handle it. I’d go crazy. I’d go insane.” Here, she flips vocally from reptile to trapped bird, as male guitar, bass and drums race orgasmically into a psychedelic disco trip. “You,” she confesses to the man, “Are my rhythm.” She needs his masculinity, deep inside her. In ‘Your Mama Wants You Back’, sexy Mama is not more than her man. She is desolate without Papa.

She frequently, especially in her work with Funk House, spaces out her own vocal performance to bring the serpentine spunk of her male band – and their voices – to the fore. She could sing hauntingly sweet but occupied the ugly back of her throat and the face-mask of falsetto to rip “the lovely flower” of womanhood in ‘She’s a Woman’, in a pastiche worthy of Bowie.

Betty’s sex-positivity was so solitary that it was destined to implode. Voodoo drums, off-kilter keys and creepy-crawly rhythms fortell the “it” of which the film cannot speak. Radio stations banned her work. Black activists condemned her for ingraining prejudices about loose black chicks. The anxiety about being seen as sexual carrion runs deep in post-slave black culture. Even Tina Turner once admitted that she wanted to be “classy”, like Jackie Kennedy.

“This ‘Nasty Gal’ persona Betty created,” Phil Cox tells me, “Suffered so much rejection. In the end, she couldn’t keep up with it.”

Society couldn’t keep up with it. Miles raided it to bound to the top of the artistic tree then disemboweled her emotionally – and, possibly, maternally, as she says, visualising the pair of them, in the film, as monkeys: “Two monkeys. A dead baby. My baby.”

“There are two Betties,” Cox tells me, “Her creation, the Nasty Gal and Betty as she is now. The two are massively apart and deeply connected.” The psychological damage of the split enforced on womanhood is described in the song Betty ostensibly wrote for her friend Devon Wilson, Hendrix’s muse, who died of a mysterious fall in The Chelsea Hotel:

“She could have been anything that she wanted

Instead she chose nothing.

So nothing flew from the East to the West Coast

Became a fiend! She was a dancer!

Became a Harlet, she was a black Donna Queen.

Music Men wrote songs about her,

Some sad, some sweet, some said were very mean…”

Betty, not Devon, flew from the East to the West. Betty choreographed her shows. Betty wrote ‘Uptown to Harlem’, a hit for The Chamber Brothers – reclaiming Harlem as a happening music scene – hence her neologism ‘Harlet’. The obvious identification here with Devon, as with Crow, is Betty’s way of dissolving the split between “everything and nothing”; the precipitous choice facing any woman who dared enthrone herself as a ‘Black Donna Queen’.

It’s notable that the maestros who have understood her are iconoclasts who have also skimmed the void of critical misunderstanding. Iggy Pop covers ‘If I’m In Luck I might get picked up.’ Bowie, whose Young Americans comes closest to Betty’s hectic, road-trip mood, wrote to Betty, in the late 70s, thanking her for her music. And Prince saw Betty as the future. Before he died, he handed Betty’s music to protégés like Marva King, who now performs Betty’s work on tour, saying, “this is the sound.” “He went to his bedroom,” recalls Marva, of that pre-dawn moment, following an aftershow in Miami. “And brought back a disc in his writing, titled ‘Betty Davis’ which contained six tracks and said, “learn these.”

Betty succumbed to genetically-disposed schizophrenia. “They put a lock on my door,” she says. She has rescued herself through a daily ritual of meditation, cake and tea. She chats regularly to Phil Cox’s eight year old son, Romeo, coaching him to play the drums on ‘He Was a Big Freak,’ down the line. “She’s taught me that old people are like young people,” the boy tells me, “Betty’s really cool.”

But the locks on Betty, the accusations of being crazy and nasty are still leveled at women who dare to be sexually free. As Neneh Cherry, deputised by Betty to read a message at the UK premiere asked, “is the world ready for her, even now?” Betty herself, however, seems sure of today’s ‘whorey angels’ – and our onward flight. “Hello London,” she said, speaking through Neneh, “I have been on an inner journey. I know there are other women, out there, breaking boundaries…” Time has finally caught up with Betty’s crow, serving up her clitoral funk-rock to a new generation of proud harlots – and wild, happy boys.

Betty – They Say I’m Different, directed by Phil Cox, is screening in Bristol on 1 July and at venues throughout the UK in July or on demand through Lush Player