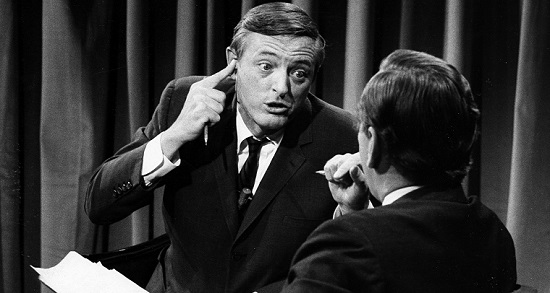

America, 1968. Racial tensions are high, the Vietnam war is in full swing and a different kind of war, cultural not military, is beginning to be waged on home ground. The country also just so happens to be electing a new president so to say this is a time of social unrest would be putting mildly. It is into this environment that the struggling ABC news network pits messrs Gore Vidal and William F. Buckley against one another in a series of televised debates, ostensibly to discuss politics but in reality to make mincemeat out of one another in mannered, parlour-room tones which haven’t been heard on TV since.

Their eight confrontations form the spine of Robert Morgan and Gordon Neville’s film which makes the case that these bust ups led directly to the partisan, fact-light, decibel-heavy state of cable news coverage today. If we are to believe the documentary’s message it was Vidal and Buckley’s sparring that prompted a eureka moment in TV boardrooms, as executives across the land realised people would gladly tune in to see pundits with polar opposite viewpoints hash out their differences.

The notion that two educated and erudite writers were in fact responsible for the intellectual descent of the media is the sort of delicious irony that seems to just ring true. A tragedy of unintended consequences with a clear, digestible message. The easy dramatic appeal of this claim is good reason to probe a little deeper into it. In fact debate as theatre wasn’t new to television in 1968. Eight years prior to the show the first presidential debates were held in America and the year before a rival channel, CBC news, had hosted a pointed conversation between Norman Mailer and Marshall McLuhan. Their exchange wasn’t quite the slagging match of Vidal vs. Buckley but it did involve sharply articulated disagreements between two public intellectuals of the day. So the combative discussions we see in the film wouldn’t have been the stark novelty they are presented as.

Why do soundbites and petty squabbles dominate American public discourse? Unfortunately there is no easy answer here. The nature of rolling news means short clips are pulled from interviews and played in a daily loop; the architecture of the internet tends to favour videos which are brief and punchy and of course corporate interests prioritise cheap (but profitable) entertainment over the promotion of public understanding. Best Of Enemies doesn’t give a look in to any of these points. It simply draws a straight line from Buckley and Vidal to more recent televised shouting matches.

The actual footage of their debates is a window into a different world: a time when weighty world issues were discussed in mannered tones by distinguished gentlemen. Still this was the sixties so there is a cultural familiarity to the way they carry themselves: both were part of a generation for whom it was important to reject received wisdom and go against the grain. More’s the pity that in a film which ran over one and a half hours less than fifteen minutes is given to chopped up segments of these reels, which are sandwiched between a familiar merry-go-round of talking heads and pundits. The upshot is that sitting through the film is a bit like being stuck in a washing machine: a jumble of different elements thrown together in an airtight container. The documentary would have benefited from a looser editing style and more footage of the actual subjects. After all, it’s not like it’s hard to come by. Buckley hosted a TV show for thirty three years and Vidal famously said “I never miss a chance to have sex or go on television.”

The perennial problem of documentaries which deal in commentary is that by worrying about being boring they fall into spoon-feeding the audience in drips and editing out the longer, fuzzier bits which complicate the message. Best Of Enemies is no exception: quick edits flit from sentence to sentence and commentator to commentator. Everyone gets their moment in the spotlight but few get more than a moment. A director with more vision would have had the confidence to present her material without these constant parentheses. Errol Morris, for example, has made spellbinding films entirely out of single conversations.

The elephant in the room here is that the directors want to criticise the sound-bite driven nature of the news media but have chosen to make a movie consisting primarily of sound bites. The famously labyrinthine sentence constructions of William F. Buckley jr. have been chopped up and made into quotations to support different pundits’ points of view. The only time a conversation is shown unfolding in real time is a snippet which leads up to a bitter, personal feud. We are not miles away from the world of Fox News here. There are some gems in this film. The archive reels of the debates are historically important as well as being great drama but unfortunately they have been cut and pasted, staccato-like, into an overly simplified narrative.

Best Of Enemies is out now