Critics and audiences have been getting Barry Lyndon wrong since it first emerged 41 years ago. It doesn’t help that, in the intervening time, its director Stanley Kubrick’s better-known works have been fulsomely embraced as paragons of highbrow genre cinema – films that, so conventional wisdom goes, lent a grand, intellectual weight to widely recognised, crowd-pleasing formats. You’ve got your swords-and-sandals epic (Spartacus), deep-space SF (2001: A Space Odyssey), dystopian SF (A Clockwork Orange), war movies (Paths of Glory and Full Metal Jacket), sex films (Lolita and Eyes Wide Shut), Stephen King gorefest (The Shining) and gonzo, nuclear comedy built like something right out of MAD magazine (Dr Strangelove Or: How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Love the Bomb).

All richly appetising stuff, and compelling evidence that a New York showman with a shrewd instinct for the saleable always remained beneath the haggard, bearded surface of the inscrutable, Hertfordshire émigré that Kubrick became – even as his style veered more and more towards European modes.

Never really welcomed among that pack, Barry Lyndon has unjustly borne the cross of ‘Stanley Kubrick’s Merchant-Ivory Production’, garnering a rough rep as a staid and stodgy period piece tugged from the musty pages of a largely forgotten Thackeray novel – unlikely to yield the type of instantaneous pleasures offered by such visions as droogs on the rampage, spaceships doing ballet, Peter Sellars in triplicate, Kirk Douglas being crucified or Jack Nicholson violently assaulting a door. Neither are Barry Lyndon‘s credentials burnished by the awkward truth that Kubrick only made it as a fallback plan when a long-gestating biopic of Napoleon – set in the same era – imploded. And then there’s Steven Spielberg’s wildly unhelpful remark from a 1977 Sight And Sound interview that, for his money, Barry Lyndon was "like going through the Prado without lunch".

At which point, with the odds now stacked to the rafters against this article’s cause celebre, it’s time to tell Mr Spielberg exactly where he can shove the Prado (sideways, sir, if you don’t mind). For Barry Lyndon is not just a hidden gem in the Kubrick canon that struggles for attention among glitzier company. It is, by monolith-shattering light years, the director’s greatest achievement – certainly the Kubrick Fan’s Kubrick Film; the one that his most ardent devotees consider to be the optimal showcase for all of his finest flourishes: ravishing symmetry, plunging depth-of-field, immaculate script structure, clever casting – every supporting player as crucial to the overall mosaic as the leads – and outstanding performances, particularly from co-stars Ryan O’Neal and Marisa Berenson. Oh, yes… and matchless, faultless music timing – the kind that, if you really focus on it, sprains your mind with its agonising levels of concentration.

As if he’d decided to filter the grotesque caricatures of Dr Strangelove through the sharper, more incisive gauze of Paths of Glory – a film that made a forensically acute critique of military mores in World War One – Kubrick hatched a real one-off in his catalogue: a deft, witty and quietly crushing social satire, replete with sardonic humour of the most patient, yet devastating, sort. As befits a film in which so many important scenes are lit entirely by candles, the experience of watching Barry Lyndon is akin to looking on as a burning wick slowly destroys a wax effigy – the figure in question being O’Neal’s Redmond Barry, a mollycoddled pauper-cum-parasite on a rake’s progress from the penury of rural Ireland to the bosom of aristocracy, via various strata of European society, in the mid-1700s. It is, to all intents and purposes, the direct antithesis of Merchant-Ivory: a period film that wryly comments upon itself, rather than furrowing its brow in earnest – gently ushering its protagonist towards his downfall with a sad, resigned knowledge that the universe will underwrite a chancer’s gambits only for so long.

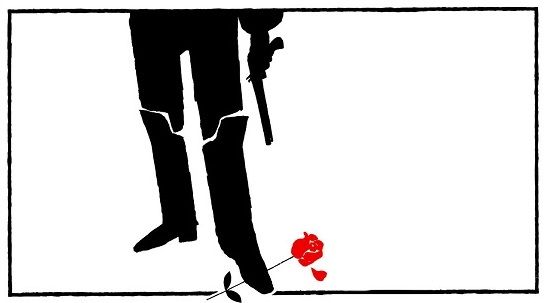

Kubrick strikes upon the film’s knowingly fatalistic timbre from the first moments of Part I: By What Means Redmond Barry Acquired the Style and Title of Barry Lyndon. As we open on a distant shot across an Irish meadow of two men drawing pistols against each other, Michael Hordern’s urbane, avuncular narration – playing almost like an 18th Century gossip column read aloud, and a key tool in the film’s ploy to stand graciously back from its own world, even as it embellishes it – confides: "Barry’s father had been bred, like many other young sons of a genteel family, to the profession of the law. And there is no doubt he would have made an eminent figure in his profession…"

BLAM.

"…had he not been killed in a duel, which arose over the purchase of some horses."

That choice of exit inevitably saddles Redmond with the baggage that will force him to pull himself up by his bootstraps – yet ultimately stumble over those very same fastenings. Redmond’s mother seizes the mantle of widowhood and ploughs all of her energy and attention into her son. In turn, his close attachment to familial females drives him into a romance with his cousin, Nora, who speedily drops him for captain John Quin: a gleaming, comic turn from Leonard Rossiter, returning to the Kubrick fold following a brief stint on 2001. Arriving in the backwater burgh of Bradytown with his Kilwangon Regiment – a local British Army troop recruiting its way through Ireland before joining the European wars – Quin imbues Redmond with envy for the ‘scarlet coats and swaggering airs’ of army life, yet not a sliver of respect. In little time, Redmond echoes his father, challenging Quin to a duel over Nora’s hand.

With Quin apparently dying in the contest, Redmond has no choice but to flee to Dublin with all of his mother’s savings until everything blows over – but before he can get there, he is unhorsed and rendered destitute by a pair of highwaymen armed with well-aimed flintlocks and mordant wit. To assure himself of food and shelter, Redmond enlists with another British Army regiment, on training manoeuvres at a nearby castle. Once he has earned a credible place in its ranks, in rides Quin’s former lieutenant, Jack Grogan, who’d taken a shine to Redmond in Bradytown, admiring how stubbornly the boy carried a torch for Nora. Grogan confesses that the shot Redmond fired in his duel with Quin was nothing more than a ‘plugget of tow’ – a cotton ball of a type normally used for cleaning out a gun barrel. Quin survived: the duel was rigged to get Redmond out of the way, enabling Nora’s family to marry her off to the captain and benefit from his debt-curing income of £1,500 per year.

That bombshell duly dropped, there seems little else for it. Redmond takes off with the regiment to Germany, diving into the Seven Years War – and, after weathering just a handful of those years, promptly deserts. Accosted by the Prussian Army, he is immediately pressed into its service – a far grimmer and more brutal existence than even the lowest points of life in the regiment he fled. Following an act of valour in a besieged fort, Redmond is promoted and sent to Berlin to spy on the activities of the Chevalier du Balibari – a self-styled Franco-German baronet who is, in fact, an itinerant, Irish gambling cheat. It’s here – not even halfway through the film – that Redmond’s choicest opportunity slowly reveals itself. Betraying his Prussian spymasters, Redmond absconds with the Chevalier, heading off on a larcenous card-playing tour through the ancestral seats of Europe’s wealthiest landed gentry – eventually clapping eyes on the Countess of Lyndon (Berenson) and seeing her, under the Chevalier’s mercenary influence, as a walking meal ticket and stately-home doormat.

To find out what happens in Part II: Containing an Account of the Misfortunes and Disasters Which Befell Barry Lyndon – or, rather, the way it happens, since that title card would appear to convey the general gist – you’d do well to lie, cheat and fornicate a path to your nearest reputable cinema from Friday 29 July onwards, when Kubrick’s gem romps back to the big screen for a much-deserved rerelease. This writer has been lucky enough to see a preview of the new, digital print that the BFI has whipped up for the occasion and, as with the venerable body’s recent, electronic transfer of 2001 – which played to packed houses on the South Bank almost two years ago – the sharpness and attention to detail are staggering. Among the many aspects of Barry Lyndon that have taken on fresh life in its digitally resprayed form, there are some that particularly stand out:

Ryan O’Neal’s lead performance is flat-out astonishing, and confoundingly under-acknowledged. This is, in every sense, his captain Willard or Michael Corleone: a whole, three-dimensional figure who feels more like a real person than a scripted character worn by an actor. Groomed as a romance magnet on the sets of TV soap Peyton Place (1964-1969) and classic weepie Love Story (1970), O’Neal developed chops on this film that would serve him well in the muscular, amoral world of Walter Hill’s The Driver (1978). With his easy-going brogue and butter-wouldn’t-melt demeanour, he engages utterly – even as Redmond’s taste for flamboyant costume and casual violence lump him increasingly in the same, sociopathic category as Malcolm McDowell’s Alex from A Clockwork Orange. O’Neal sells Redmond’s three-hour transition from sympathetic underdog to contemptible bum with exquisite subtlety.

Marisa Berenson doesn’t even make her first appearance in the film until the 99th of its 187 minutes, but more than earns her co-star billing, exuding ornate poise and bone-China fragility as a woman who doesn’t realise she has let a morally rabid dog into her home until it’s too late. Drawn at first to Redmond’s chivalric veneer – a mirage cultivated on the Chevalier’s watch – the Countess of Lyndon eventually crumples into the countenance of a bagged-up cat that has been hurled into a river in the company of a brick. Never much of a household name, despite her superb showing in the film, Berenson follows Lolita‘s Sue Lyon and 2001‘s Kier Dullea in the distinguished line of ace Kubrick finds that are almost wholly identified by their work with the director.

Leon Vitali, who plays Lord Bullingdon – the Countess’s son by her first marriage – excels as the man who is on to Redmond from the start, when his younger self is played by the equally well-cast Dominic Savage. In one powerful scene, when Bullingdon berates Redmond in front of his entire social circle, triggering an incendiary reaction, Vitali delivers what is arguably the film’s best speech, and is never less than totally believable as someone who holds the divine right of lordship close to his heart. Driven by a clinging devotion to his mother, Bullingdon is characterised as perhaps too similar to Redmond in certain, important respects for them to coexist even on the same land mass – let alone on opposite ends of a vast, country manor.

Wheeling us around and between those tremendous turns is some of the most maddeningly composed camerawork ever committed to celluloid. More than any other Kubrick film, Barry Lyndon demonstrates why Francis Ford Coppola lined the director up with Fellini, Bergman and Kurosawa in his personal league of the world’s greatest filmmakers. The wide-open clarity with which the camera bears witness to Redmond’s social ricochets – which could have been chaotically drawn in the hands of a lesser talent – leaves the viewer with only one impression: that Kubrick used the camera as an organic extension of his sense of sight.

There is nothing about the sweep of his gliding camera moves or the naturalness of his static compositions that hints at the use of equipment, or even a crew – it feels entirely as though the film is being beamed on to the screen straight from the uncluttered, optic nerve of one individual, who viewed the world in a highly specific way. Given the vastness of his outdoor and indoor locations, Kubrick often turns the audience into a collective interloper – hanging back behind rock walls or hedges, or nestled into the corners of palatial parlours, watching on as the characters play out their games of inter-personal chess. That stylistic rigor blends with Hordern’s narration to ignite Barry Lyndon‘s streak of self-awareness – but its knowing tone is never remotely cocky or flippant.

And, oh! That music timing. Taking its cue from 2001 and A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon maintains Kubrick’s thesis that some of the world’s greatest film soundtracks had already been written centuries before the dawn of cinema by composers long since decomposed. Excerpts of Bach, Schubert and Mozart are applied with painstaking care for how they will straddle scenes and assist the invisibility of the editing. Then there are moments that simply celebrate the metre of the music, as in one scene where Redmond struts into the office of Berlin’s minister of police, and his halting double foot-stamp before the official’s desk is exactly in time with the final two beats of a Mozart march. But far and away the film’s grandest musical presence is Handel’s ‘Sarabande’. This minimal, stately stride of a piece (which standup fans will instantly recognise as the tune that backs Dave Gorman’s ‘found poem’ readings on Modern Life is Goodish) is used as a powerfully insistent leitmotif – either blasting away at full strength at the top and tail of the picture or, at key moments between, creeping out as a more muted creature, whether picked out on a cello or patted gently upon understated drums. Just like the camerawork and narration, ‘Sarabande’ appears to raise a headmasterly eyebrow at Redmond’s self-authored predicaments, as much to say, "Oh, really?"

For a film that has tended to be woefully sidelined in standard conversations about Kubrick’s output, Barry Lyndon has nonetheless exerted a tidal influence. Milos Forman’s Amadeus (1984) seems particularly beholden to Kubrick’s great symphony, not least in its treatment of Mozart as a boorish oaf – albeit a far more talented one than Redmond – at large in Europe’s aristocratic courts. It’s also impossible to think that Ridley Scott’s The Duellists (1977), Stephen Frears’ Dangerous Liaisons (1988), Bernard Rose’s Immortal Beloved (1994), Jake Scott’s underrated Plunkett & Macleane (1999) or Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette would look, sound or behave quite the way they do, had the candles of Barry Lyndon not lit the way.

So, "like going through the Prado without lunch", huh? Au contraire: there has rarely been a more substantial audio-visual feast. In making Barry Lyndon, Stanley Kubrick left us with a table-buckling, five-course roast of a film, heated by the open fire of his imagination and awash with the fine wine of his intellect. Help yourself to a serving of this moreish masterwork, and enjoy in discerning company.

Barry Lyndon is rereleased on Friday 29 July

Find Matt Packer on Twitter at @mjpwriter