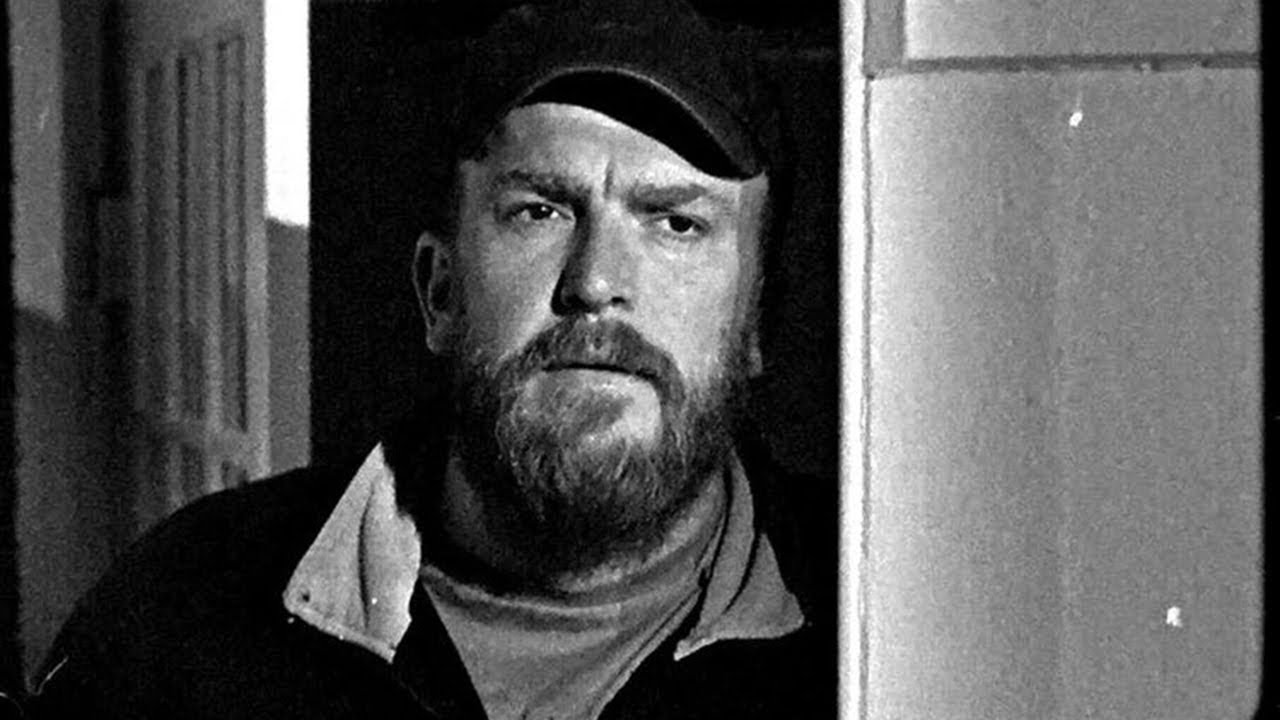

Image courtesy: Bait film

I saw Bait at the Berlin Film Festival and chose it randomly based on a still and a short descriptive passage.

On the same day I also saw Derek Jarman’s The Garden and felt that I was seeing two unrelated films. However, the two pieces battled for a similar place in my brain until Bait eventually won. I shouldn’t have been surprised to learn that The Garden was an influence on the director of Bait, Mark Jenkin.

Bait is set in a small village in Cornwall. It concerns a fisherman without a boat and a family with two homes, one of which used to be the fisherman’s. It’s a film about the effects of the tourist trade on small communities. It’s about places that used to produce and build but were tempted by things they couldn’t say no to. It’s about the pain of being unable to reverse time.

“You didn’t have to sell us this house.”

“Didn’t we?”

For me, also, it’s about ownership and boundaries. What we think is ours. What we have to accept is lost or unattainable.

The middle class family who own the fisherman’s family home have all the legal rights, they have their name on the forms. They come to realise however, true ownership comes from somewhere else. They are there, but they don’t belong.

Martin (Edward Rowe) , the fisherman, does belong but time is relentless in its corroding effect. He can’t put his name legally to very much, certainly not a boat, or a house, but his rights remain vital to him: his right to earn a living, his right to stay where he calls home. His old boat now runs tourist trips and is owned by his brother. Martin seethes. Everybody seethes.

The plot is set off by the most common of boundary disputes, the parking space. Bait causes you to reflect upon your own territories. What you consider to be yours that you do not own. We all have a small private war somewhere.

It may seem a picture of right and wrong but what makes the film remarkable is Jenkin’s ability to make you sympathise with every character. All of the characters are both reasonable and unreasonable. You want them to all get what they want.

The story isn’t black and white but the film is. The picture is coarse, fractured, and starkly monochrome. The image constantly pulses with light. Cracks and scratches splinter across the screen. This is where you see the connection between Bait and The Garden. It’s impossible to talk about either without discussing the way the films look.

The Garden uses video, film, back projection and everything jars. You can’t quite tell what is purposeful and what is error.

Bait was filmed by Jenkin on a 16mm 1978 Bolex camera. He developed the film himself introducing coffee, washing soda and vitamin C powder into the process.

It’s a startling looking film and much like The Garden it immediately makes you question how much of what you see is intent. Jenkin enjoys this tension himself, setting up rules that means he is flying with no parachute. There was no digital back up on set, no undo button. He only knew if he had a film at all when he started developing the first reels.

I have honestly never seen anything like it, well, I have, but they were films made in the 1920s. Filming a contemporary story in this style gives Bait a curious allure. It’s like watching the present through a fine fishing net. It’s as if you’re watching an artefact that’s been buried, and then found. Except it happened yesterday.

Other elements also remind you of early cinema; faces are shot in close up. Reactions are blown up across the frame. The acting and editing have a curious pace to them. Everything is clear and emphatic but the work as a whole is beautifully subtle and deft.

The most admirable thing about this technique and process is that you come to forget about it. Strict working practices can sometimes lead to art being only about art, but this isn’t a filmmaker’s film. Mark Jenkin is a patient and intelligent storyteller. Everything slowly unravels and you care enough to gasp at the life twists thrown at our characters. Bait creates a world that is simultaneously real and unreal. It is a fantastic version of something completely believable.

The film was made using what the producers call “a light footprint” in that it was filmed on location with careful consideration for the community. Local services and products were used in the making wherever possible. The filmmakers were interested in the randomness of errors, but avoided the errors made by the characters in the film.

Love pours out of this movie. It is such a rich and rewarding project. At its heart however is a deceptively simple story about the ghosts we carry with us. It’s about the fear of change and the danger of prettying the past.

Bait, directed by Mark Jenkin, is in UK cinemas from 30 August 2019