"My little story is the only thing between you and a gun to the head." Tony Mendez

The tension between fiction, which is supposed to ‘work’ narratively, and real life, which rarely does, is present in most films ‘based on a true story’. Ben Affleck’s Argo handles and exploits it exceptionally well. Argo is about many things, but what ties it together is its concern with how we tell stories and how we hear them and its faith in the power of narrative. It’s not only about the reasons people need to construct satisfying narratives, it’s about the dirty, disordered business of doing so.

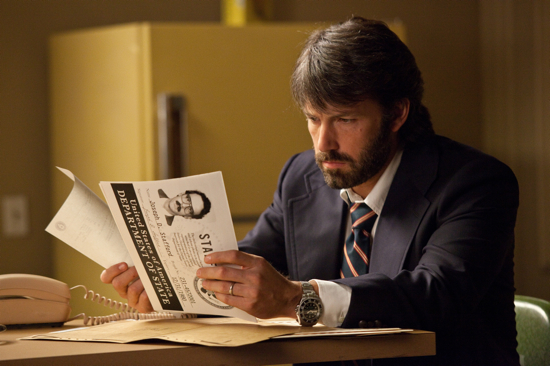

Argo is a dramatised account of a secret CIA mission (which was only declassified in 1997) to rescue six Americans from Tehran during the Iran hostage crisis of 1979-80. The movie opens with a gripping, unsettling recreation of the storming of the American Embassy by Iranian citizens protesting against the US’s continued protection of their exiled Shah. Only six of the embassy staff escaped immediate capture. Two months later, they’re hiding at the house of the Canadian ambassador, Ken Taylor (Victor Garber), and the CIA is getting antsy about their safety. So they bring in Tony Mendez, an operative who specialises in ‘exfiltration’ – rescuing people from dangerous situations in hostile countries. Affleck plays Mendez in his own film, just as Mendez directed and acted in the CIA operation.

Mendez’ audacious rescue plan involves staging a location visit to Iran for a fake film production. Appropriately, the narrative device of film within a film, offers an interesting parallel with some of the Iranian new wave’s best known work, such as Abbas Kiarostami’s Through the Olive Trees (1994). The CIA man’s ‘Argo’, though, is to be a shameless Star Wars rip-off, carefully detailed to be exactly as persuasively unoriginal as it needs to be to fool not only the Iranian Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, but also the Hollywood gossip machine. If they can convince Variety, the job’s half-done.

Argo boasts a stellar ensemble cast (including Alan Arkin, Bryan Cranston and John Goodman), but the story and film belong to Tony Mendez, and in parallel to Ben Affleck. Mendez had to remain cool and confident at all times, even under the terrible stress of telling complicated lies to men with guns, short tempers and a hatred for Americans. Affleck’s performance is wonderfully subtle. Whether at CIA headquarters, in Hollywood or Tehran, he inhabits Mendez’ persona with just the right levels of calm authority. Only his eyes sometimes betray unease, but the success of his plan is entirely dependent on creating an illusion – and it’s an obvious metaphor for the success of the film itself.

Affleck’s direction mirrors his performance. Assured and authoritative, the movie carries us through the complexity of the political situation and the absurdity of the Hollywood machine with barely a misstep. It’s a mature confidence, and much credit must go to Chris Terrio’s terrific script for this too. Argo doesn’t need to rely on constant action to propel the story forward. It’s equally gripping in its reflective moments, whether observing the fugitives in relative safety, exploring the effects of the situation on ordinary Iranians, or turning to affectionate comedy in the Hollywood-set episodes.

Politically, Argo is refreshing. It doesn’t shy away from acknowledging the American and British complicity in creating the terrible situation in Iran that led to the storming of the embassy, even as it allows the viewer to cheer for the uncomplicated heroism of the individual Americans. The attention it pays to the lives and feelings of ordinary Iranians is essential to achieving this – every character is treated with respect and sympathy. The anger of the Iranian market trader screaming at the Americans is equally as justified as that of the Americans waiting while their relatives are held hostage.

Argo‘s production design is excellent. Its late ’70s milieu is painstakingly and unshowily created. The CIA headquarters in Virginia are constructed, designed, and dramatised taking cues from classic spy thrillers like The Sandbaggers. Argo understands the unique thrill of espionage in an analogue age: a great deal of tension comes from unreliable telephone connections and the lack of answering machines. But it’s also an age of mass media. The private, confidential story unfolds against narratives the media creates, with TV news providing a constant public commentary over this secret history.

A dissection of Hollywood’s foibles is the light side of the story, and the satire of these sections flirts with broad comedy. That they work with the gripping, desperate Iranian and CIA scenes to form a coherent, satisfying narrative is a tribute to the excellence of the screenplay, direction and performances. The film has total confidence in itself, like Mendez’ plan, and deservedly so – it’s utterly gripping from start to finish. It pulls off the feat of giving complex issues the time and space for consideration they deserve, but at the same time rattling along at such a pace that there’s very little room in which to question its authority. It juxtaposes comedy and tragedy without compromising either. This is terrifically exciting and satisfying filmmaking.