To listen to Aretha Franklin at any moment is exhilarating and one of the undoubted pinnacles of her illustrious recording career is the live gospel record Amazing Grace. To see her in the finally constructed and released concert film that captures the recording of that record is something else, almost entirely. Seeing is often believing, but it’s equally as often – particularly in the realm of the concert film and music documentary – disbelieving.

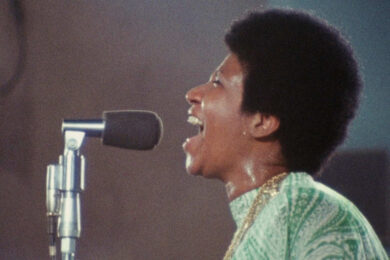

The disbelief experienced watching Amazing Grace is vast. Disbelief that a human body could produce this sound and not only that, but command it and bend it and shape it to the will of this small woman from whose frame this thing emerges. There’s disbelief also at how little is needed to enrapture. A great band and bandleader, a great choir and Aretha. That’s really enough. She stands behind a pulpit surrounded by thrusting and hanging microphones. Wires are everywhere, camera operators too. It is a strange sight and she stands (or sits occasionally, at her piano) at the centre, and sings. The simplicity is a stark jolt reminder of how much spectacle and show has come to be the first and most powerful signifier of live music.

The overwhelming power of Aretha’s voice and seeing her sing these songs transcends the aesthetics of the film and the extreme contrast between her poised and stoic presence. The viscerally physical reactions of the choir and the members of the audience is dizzying. Reverend Cleveland, the esteemed pastor of the New Temple Missionary Baptist church in Los Angeles, where the recording takes place, is seen at one point weeping during Aretha’s performance of the title track and at another, so full of disbelieving joy that he flings his towel at a nearby camera with a delicious grin on his face. From the opening frames to the last, the film knows that it is capturing lightning in a bottle. Everyone in the room and watching in a cinema knows they are in the presence of someone and something special.

Shot over two nights, the film is seamlessly constructed from the original materials, which also includes a small amount of rehearsal footage from the venue. It’s pretty well known now that Sydney Pollack handled the recording of the concerts poorly. At the time he was an emerging Hollywood director but someone unfamiliar with the demands of live event filmmaking – though he can be seen directing throughout and it’s clear he knows what to capture. At one point he instructs his team to ensure that gospel matriarch Clara Ward is recorded when the emotion gets to her and she drifts into fevered revelry.

There was no way to sync the sound recordings with the footage after the fact and, as it was not done at the time of recording, the hours of material languished in storage, unusable. When the technology became available to do this, Aretha herself refused to let the film be finished and released. It arrives now, in the wake of her recent passing, and with it come questions of whether it should see the light of day as it was never made clear how Franklin would feel about it coming out after she died.

This unanswerable question aside (though rumours of the reasons behind her refusal to let it screen including invasion of privacy have circulated for years), it would be a disaster for cinema and music history were this incredible film never released. Hyperbole be damned, because beyond the sheer joy resulting in the experience of seeing arguably the greatest singer of all time at her peak absolutely slaying, the film as a document is vital in redressing some of the erroneous legacy of the music documentary and concert film form.

The sight of Mick Jagger and Charlie Watts slinking around on night two, having heard about the events of night one, opens up the history of the form to shameful scrutiny. There are countless examples of the white giants of the 60s and 70s strutting their stuff on stage, running from screaming fans, standing stock still in the middle of arenas and stadiums as their adoring fans gaze on. However, there is a shameful lack of cinematic documentation of black artists of similar cultural stature to the Stones, Dylan, or The Beatles in their prime.

This film is a necessary counter to a narrow history. It’s also vital because it’s not simply on stage and in the choir that black faces are prominent, but in the audience. What might the canon of concert films have looked like had this been released back in 1972 or 73? Of course Jagger is there, piggybacking on the cultural labour and leisure of black America, but even he can’t wrestle the significance away from Aretha and those who worship her and the God she channels over the course of two incendiary nights. She is a sublime presence in the film, confident in her gift and abilities and she knows how to put on a show. She just sings.

As if more evidence were needed of her craft and professionalism, there’s a stunning transition from Aretha in rehearsal to Aretha in the show, her voice pitch perfect and powerful whatever the occasion. She always showed up when there was a mic.

The footage is remarkable and the editing impeccable. The two nights are weighted beautifully and there’s no danger of asking how will night two top night one, because at the end of most renditions the question is asked, how can she top that song? This is asked early. Following the choir’s entry, Aretha arrives and takes her place at the piano for a version of Marvin Gaye’s ‘Wholy Holy’ that is simply devastating. From there the level of artistry, control and performance just goes up and up and up. By the time of the finale of night two, with Aretha again at the piano delivering an extraordinary ‘Never Grow Old’, the whole place is in pieces – the band, the choir, the reverend, Aretha’s Father (who flies in for night two), the film crew and, of course, the audience.

Seeing her sing these songs, seeing the joy and devotion she inspired, seeing how incredibly she handles the machinery of her body to make notes that seem impossible, does something extraordinarily rare in concert films or music documentary. She elevates the recorded material to somewhere not just new, but unique. Ninety minutes in the presence of such greatness and the result is gratitude and humility at having witnessed such an event, but also, still, disbelief at how she could do it. Even more impressive was getting a room full of film critics clapping along at the end credits at the film’s European premiere at this year’s Berlinale where I was honoured to catch the film. The magic of cinema. The magic of Aretha.

Amazing Grace, directed by Alan Elliott and Sydney Pollack, is in UK cinemas now