To horror and sci-fi fans Alan Howarth needs little introduction. Perhaps best known for his series of collaborations on the soundtracks to many of director John Carpenter’s most famous films – including Escape From New York, Prince Of Darkness and Big Trouble In Little China – Howarth has also been part of the sound department, coming up with innovative and ground breaking audio effects, for movies including Raiders Of The Lost Ark, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Total Recall and nearly all of the Star Trek films. In London this Halloween weekend for ‘Chills In The Chapel’, two shows in London’s Union Chapel in which he will play selections from the soundtracks to Escape From New York and Halloween, Howarth took time out to talk to The Quietus for an in depth chat about sound design, psychedelic rock and working with one of the masters of horror.

You started off playing in rock bands in Cleveland, is that right?

Alan Howarth: Yeah, In 1967 or so I started playing high school sock hops with a band called The Tree Stumps. We won battle of the bands and opened up for Paul Revere And The Raiders. That band modulated into another one called the Renaissance Faire, which was more of a west coast influenced band – we were really into The Doors and Jefferson Airplane and Quicksilver Messenger Service. We actually opened for Cream on the Wheels Of Fire tour. That band modulated into another band called The Silk, which was kind of fun because we opened for The Who when they were on the Tommy tour.

What did you learn from rock that you bought forward into electronic music?

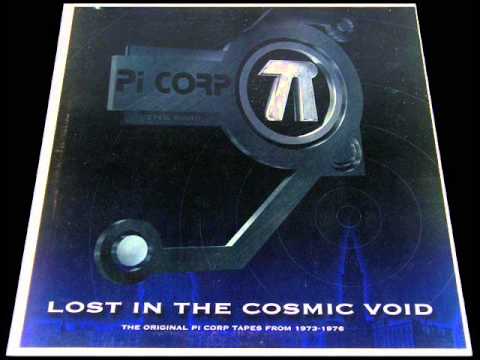

Pete Townshend from The Who was into synths. He had his ARP 2600 and they had tape playback for ‘Won’t Get Fooled Again’. Moon had headphones and played along with the track – they were so dynamic. The other thing I was impressed by is that after the second night we opened for them they were still doing this amazing act. I was like “Wow, this is the Olympics of rock and roll. This is what the real guys do…”. That really influenced me to not just be a drunk, stoned out guy, but to take the show seriously and be dedicated to doing a performance. From that period I went into a long period of creating my own music. The first band was called Braino. I was the main guy and had a drummer and bass player with me. I got twin Echoplexes and a little cheesy organ and a bench oscillator, but I played it through the Echoplex and it made weird noises. That was the beginning of the electronic music part of the deal. The sound man from Braino signed up with Weather Report and at a certain point I got invited out on the road with those guys to take care of the synthesisers. That put me with Joe Zawinul who had Arps and Prophets and Oberheims. I was like the butler, out there taking care of stuff on the road. During that period Braino modulated into a band called The Pi Corporation and that’s when I bought an EML 101 and added a real synthesiser to my rig. We did this long period from about ’72 to ’76 where we rented this funky office over a pawn shop and would go over there and jam every night.

What electronic music were you listening to at that time?

I was listening to Stockhausen and all those other guys when I was in high school. I remember doing a paper where I had to argue whether that stuff was really music, because it got called ‘noise’. My argument was that the basic definition of music is the alternation of sound and silence, so it doesn’t matter what sound you’re making, if you turn it on and then turn it off you’ve made music. I stuck with that viewpoint for a long time.

It was the late 60s, I wouldn’t want to incriminate you in any types of behaviour, but there was a a lot of thinking about altered states and different ways of being. Did you indulge in those kinds of ideas?

Absolutely. It was an experimental time, you wanted to see what was out there that you didn’t already know. Astral projection, drugs, sex and rock and roll – the whole nine yards! Things like acid and weed were part of our culture, but it was there to be mind expanding. In fact, later on when the football players started getting high I was like “Aw, man…”. That stuff was so special and then it became like beer. Those guys missed the boat completely.

So you ended up getting involved with the Star Trek film?

Yeah, I was out with Weather Report and a friend of mine was in Los Angeles doing a job for paramount pictures. There were these two guys talking about how they needed synthesisers to make sounds for this movie they were working on and he turns around and says “Man, you’ve got to talk to my buddy Alan, he knows all about synthesisers”. They were open minded and gave me a call. I went down and they were making the Star Trek motion picture. My audition tape was to make a sound like The Enterprise going from warp one to warp seven. I had a little set up in the dining room of my house in LA, so I made this filter sweep tone that kept rolling over itself. I turned in that tape and it became the sound of The Enterprise. I was on for six more Star Treks after that, making transporters and lasers and whatever else was happening. Interestingly enough the picture editor of that first Star Trek, his next movie was John Carpenter’s Escape From New York. I got invited to do sound effects for Escape…, but then there was a golden moment. Dan Wyman, who had worked with John on the music for The Fog and Halloween, wasn’t available and Todd recommended me. Carpenter came over to the same studio I was making Star Trek in – my dining room – and sat down with me for a couple of hours. I played him some music, we played some sounds and before he left he said, “This is great, let’s do it”. So I was now scoring Escape From New York. It was a blessing from the sky, no agents, no heavy Hollywood scene, just guys.

With the Star Trek stuff were you using natural sound at all or was it purely synthesised?

I started off doing stuff on synths, but the next part of the journey was when they started asking for organic sound. Electronic sound was fine for the bridge of the enterprise or imitating a star ship but what about explosions? What about physical effects? That meant audio recordings, so I started manipulating sound on tape. The tape loops were literally loops. They were quarter inch tape that was spliced together and run around a couple of microphone stands around the room. It was about 30 feet long. You’d re-record that into the eight track which I’d modified so it had a varispeed that I could play with. I had a spring reverb and a couple of effects but it was really the manipulation of tape that was the deal. The tools of the day were what was available.

Is there anything about the quality of working with tape that you prefer to digital?

There’s certainly properties to tape that are mechanical and physical. On a computer you can’t get a tape running and rewind it and drop it on the head to get a weird sound. There are things that tape did that there isn’t any hope of computers doing because it’s random and you’re touching it – you’re actually spinning stuff. Things like reverse reverb. On a tape recorder you turn the tape backwards, run it into a reverb and record it again. I used that effect in Poltergeist when I did the voice of little Caroline. There was discovery in just taking things and making them do stuff they were never designed to do. There was a lot of mechanical and physical sound creation that you couldn’t do with a piece of software.

There’s something really psychedelic about abusing technology in that way.

My mission was to make sounds that didn’t exist in reality, whether it’s a star ship or a laser or a monster or an exploding planet. You started with basic sounds that were acoustic and then you manipulated them. There’s a scene in Raiders Of The Lost Ark, when he falls into the well of souls and pushes over that statue and there are all those snakes? The sound of the snakes was made by pulling masking tape off glass. When the statue falls over and breaks the wall there’s the noise of lots of big rocks breaking. We just took some bricks and smashed them up and then slowed the tape recording down. I remember doing a lot of great scary effects using dry ice and a bunch of pots and pans out of the kitchen. You heat them up really hot and then you drop a load of dry ice into the hot pan so the rapid thermal change would make it scream. It was experimental, that was the cool part. We were cutting new turf and going to a place that, at least as far as I knew, had never been gone to before.

It sounds like fun!

It is fun! There’s a new project I’m on, working for a company called Magic Leap. They’re developing augmented reality. Virtual Reality is when you put the mask on and you’re in a 3D world, but with these guys the next twist is to put on equipment and you still see the actual world you’re in, but now there’s the projection of holograms into that real world. So there could be a baby elephant in the middle of your living room! Sound has to be attached to that and spatialized and positional to add to the illusion, so I’m on board to figure that out. I’m as excited by this as I was when I did the first Star Trek. I’m experimenting again and doing all kinds of crazy stuff.

What was the division of labour on the John Carpenter soundtracks? Who was doing what?

When we first started my job was to make sure the red light was on when we played. I had all the equipment and he had the ideas. Because it was his movie, he would sit down and make the first pass on what the themes were – he’s a master of themes – but all that sequencer work would be mine using the ARP.

There’s a simplicity to the John Carpenter soundtracks, what led you to that approach?

Neither he nor I knew what we were going to do until we did it. The main title theme to Escape… he did at the very end. After we’d done most of the movie the beginning was changed because there was a scene that got cut out, so that impacted what the titles would be like. There was a graphic explanation of 1997 and the world going crazy, and all that explanation became part of the opening title sequence, so we did the theme for that. But I give credit to Carpenter for the simplicity. He had already mapped out what a soundtrack for his movies should be like with Halloween and The Fog, but now with my gear and my input we reshaped it into what would be Escape…. He let me contribute so that I really felt like a contributor, not just an engineer.

And your improvisation skills are coming in here as well. You were talking about doing stuff early on in your career where you’d have to be constantly thinking on your feet. That’s obviously a situation that you’re comfortable with.

Totally comfortable with that. In fact I’m not comfortable with sitting and writing it all down. Obviously if you’re with an orchestra that’s a whole other game, but now there’s technology to improvise into a computer and get it spat back out as written music, so the technology supports my original improvisational style and makes it practical.

Are sci-fi and horror favourite genres of yours, or is it just being good with synths that has led you toward those genres?

No I enjoy that stuff – the action adventure movie a la Raiders… and that kind of stuff. The horror movies I got closer to because of Carpenter. I’d never seen Halloween when he walked through the front door of my house. I wasn’t in awe of him, I didn’t know who he was – which was fine. He didn’t want someone who was going to be a fan, he just wanted another person that was going to work with him. Then at the end of Escape… he said, “You know, we’re going to be doing a sequel to Halloween and I’m going to be busy making The Thing so you’re going to be doing Halloween now”. I went on to do Halloween 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6. I was very blessed to work with the guy and have the chance to sit in a room with him for almost a decade and have the whole world of synths get better – midi, tape recording, sampling, sequencing. There was something new every year that we added to what we did.

A lot of these soundtracks are being rediscovered. Why do you think that is? What is the quality they have?

I think the concepts that we had – the palette of sounds that we used – are now locked together with the images. I never expected to be here in 2015 talking about this stuff, but younger generations are listening to it and going ‘”hey, that’s cool…”. There’s a whole genre of film scores that are done on analogue synths. I got a call the other day, someone’s making a movie and they want me to do my old thing: “Can you set all the old stuff up and do it one more time? The way you used to do it?” I said I’d be delighted. I’ve got a couple of vintage pieces. I have a Mini Moog and an original ARP Avatar. I’m even considering doing a tape recording, but I don’t know if I want to go quite that far. But as an artist I know how to do it. I know all the tricks and the nuance to that level of simplicity, and how to keep it simple as opposed to trying to jazz it all up.

As long as you do it on the kitchen table…

I’ve got simple again. It’s interesting. I had a lunch with Brian Eno a couple of years ago, and we were talking about how equipment is so elaborate now that you have to set restrictions on a project in order to framework what you’re going to do. Then you work the heck out of what’s been prescribed. So he’ll take a band and in order to put that band on a path he’ll say “We’re only going to use acoustic drums, analogue synths and guitars” and the band make their music out of that. They end up doing things they never did before.

Keep it simple.

Yeah, the simplicity was a necessity before, but it had a quality that younger artists like. There was something to it that people are adding to their own music now.

‘Chills In The Chapel’ presents Escape From New York tonight, with Halloween to follow tomorrow. Tickets and info are available here