Towards the end of The Beaches Of Agnès, the eponymous narrator comments, "I’ve said it before: memories are like flies swarming through the air… Bits of memory, jumbled up." This lively, mischievous documentary of the life of Agnès Varda, the French New Wave’s most historically overlooked figure, attempts to marshal those memories into a somewhat coherent order. For the most part it just about clings to the proper chronology, but eventually the recollections, metaphoric restagings and emotional associations begin to arrive too quickly; to double back and clamber on top of one another. Varda, always quarrelling and negotiating with her own old age, surrenders herself, and her film, to the overwhelming disorder as she approaches the present.

It’s one of four films to be screened as part of a retrospective of the director at the Sheffield Doc/Fest from June 7-12, and its relevance extends far beyond European cinematic history or the hybridising of documentary with fiction. Really, Agnès Varda has been present, camera in hand more often than not, at a great many significant and strange world events from the Second World War onwards. The film feels like it’s been pieced together from a huge and fascinating archive – evidence of an endlessly curious creative life set in motion by her prodigious photography skills and the early success afforded to her second feature, Cléo de 5 à 7, at the height of the Nouvelle Vague’s renown. The upcoming retrospective in Sheffield seems geared towards those who are unfamiliar with her work (her more obscure output, of which there is plenty, is not represented), and also towards the latter period of her life, where she finally found the reputation and reverence she deserved, but never actively courted.

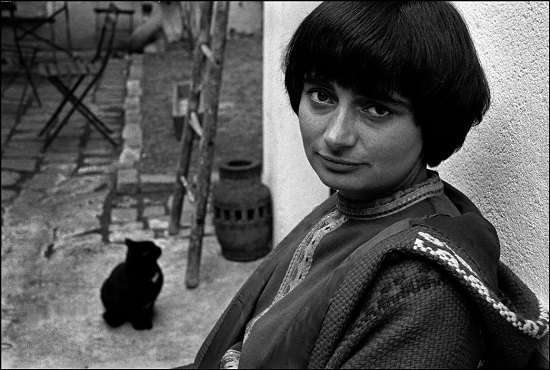

Cléo de 5 à 7 will be screened on the festival’s opening night, and is certainly as high profile a film as could be selected from her filmography of fifty-plus years. Following its protagonist, a glamorous early sixties pop singer named Cléo, through the two nervous hours before she finds out the results of a medical examination, its presence at a documentary festival depends upon a fairly loose definition of the term. Cléo de 5 à 7 is largely a narrative fiction, although many of its scenes gesture towards and borrow from documentary and vérité styles.

There’s a strong sense of romance and unfulfilled emotion running through the film, although, as might be expected from a Nouvelle Vague work of the time, these are shown to be constructions. Just as Cléo’s own fragile chanteuse personality is something of an affectation, Varda piles on the melodrama at one moment only to abruptly remove it the next. It’s this abruptness that keeps Cléo fresh and enjoyable today, long after its ideas were new. We can still feel the emotional sincerity of the film as well as what undermines it, as Varda thrusts Cléo into the vulgar streets of Paris, with its chattering café culture and ominous talk of the Algerian conflict over taxi radios. It’s hard to maintain a precious façade in such a place.

It’s this aspect of the film that warrants its inclusion as part of a documentary festival, as well as in any university syllabus charting the abstract theoretical waters of concepts like self-reflexivity, identity and gender politics. Cléo hurries distractedly along the street, looking beautifully troubled, and the reverse shots of Paris pedestrians breaking the fourth wall are at once her own point of view as a (self-) constructed woman, ours as equally lowly pedestrians, and of course anyone’s who happens to point a camera in the direction of the general public. In this case it’s probably Varda herself, poised with her trusted handheld, picking out faces.

Cléo… fearlessly packs in far more references and observations about contemporary cosmopolitan French life than it could possibly resolve in its modest running time (it reduces its supposed two hours down to less than ninety minutes). Those in the audience this weekend in Sheffield will see this is a running theme of Varda’s work: out of the restrictions of focus, structure and perspective she sets on herself a multitude of other threads and narratives will make themselves known, as if they’re crossing the paths of each film only briefly before continuing on their own way.

Vagabond, her tragic story of a homeless young woman is told with exactly this kind of narrative and formal structure. The human drama at its heart is so engrossing that you’d be forgiven for not noticing the conceptual set-up; I certainly didn’t. I had to be tipped off by Varda herself as she comments upon it in Beaches…, proclaiming it an uncharacteristically angry film. Mona is a scruffy, rebellious drifter to whom we are introduced as she lies frozen to death in a ditch, and the film recounts the few weeks leading up to her death through her encounters with others – some sympathetic, others dangerous or exploitative, all ultimately a poor fit for Mona’s character and unable to save her from a premature end.

Intermittently the peripheral characters speak directly to camera about their experiences with Mona. It’s the most overtly documentary-style technique adopted by Varda, and is totally integral to its message. How can someone fall through the cracks of society so easily? When one is already at the lowest level, the cracks can only be fatal. Some try to help her, but only on their own terms. They are aware of Mona’s death, but they can account for it no more authoritatively than how she came into their lives in the first place. Hauntingly, she has become a person of no provenance.

Much of Vagabond takes place in the French countryside, as Mona attempts to earn a few francs by performing odd jobs for either uninterested or predatory mechanics and farmers. In this, Varda’s cinema of anger, the country is just as inhospitable as the city, and Mona cannot live on the fruits of fields and orchards forever. Fifteen years later Varda returned to agricultural France, and to the plight of the poor who are forced to scavenge for their survival, for The Gleaners And I. This is a fully-fledged documentary, and now the protagonist is the film-maker herself, commenting on the portability of her new digital handheld camera as she shoots her interviews with more freedom than ever before. Of course there is an aesthetic difference (some might say deficit) between digital and celluloid, but it’s arguable that this later work represents a truer reflection of Varda’s artistic reflexivity than any fictional narrative ever could. She is under no obligation to adhere to a predetermined story or even to keep herself out of shot, and the little asides and tangents introduced in her narrative cinema are more prevalent than ever.

Thematically there is also a shift of concern from gender to class. "Gleaning" is the retrieval by local citizens of crops discarded by farmers and landowners after harvest, and many of Varda’s interviewees are either poor or outright homeless. They are filmed picking through potatoes, taking huge sackfuls and lamenting the wasteful state of society and the unscrupulous nature of the large-scale food industry. Her focus moves from those who glean to live to those who glean for the sake of art, among whom she counts herself, and finally to those who have political or ethical reasons to glean. The film’s subject is rather modest, but again this allows for those tangential and associative moments that make her films so distinctive. The camera will extract something extraordinary out of the ordinary, and Varda’s restless eye is always there to capture it, to encourage it.

This applies to herself too: because of her private concerns about ageing during the period in which she shot The Gleaners and I (she turned 70 the year before starting filming), she seems duty-bound not to exclude it from the narrative. But instead of stretching the film’s ostensible subject to incorporate it, she allows it to form a large part of her own personality and presence as the filmmaker. She muses on the marks and blemishes of age in close-up shots of her own hands; she tips out collections of souvenirs to remind her of places she’s visited; and near the film’s conclusion, she sets up a shot of herself through a clear plastic clock with no hands on its face – an item she herself had previously gleaned from the street at night. To end the film Varda shows us two sequences that struck her most profoundly during the shoot, and we get the sense that she doesn’t make documentaries to find answers, or even to find people (although her films are much more about people than objects, places or ideas), but in order to set herself on the path to finding these moments of fortuitousness and meaning, where significance seems to multiply.

Varda’s latest feature-length documentary, The Beaches Of Agnès is definitely one for the cinephiles, as the director-narrator tosses out priceless anecdotes and personal tributes to peers and collaborators like Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, Jean-Luc Godard and of course Jacques Demy, her husband of many years and easily the most important person in her life. But of course the film doesn’t just trade on legendary names; it’s also the most inventive and amusing of all the works in the Sheffield retrospective. She retraces her life’s course by way of its beaches and rivers, recreating scenes in the sand or on board boats, using photographs, props, her own possessions, overseeing playfully ad hoc set design and wearing costumes straight out of the dress-up box. Its self-awareness and postmodernism are both humorous and touching: she makes a gentle cinematic game of prompting her own memory, but the sincere undertones are always there.

"I’m playing the role of a little old lady," she tells us, "pleasantly plump and talkative, telling her life story. And yet it’s others I’m interested in, others I like to film. Others who intrigue me, motivate me, make me ask questions, disconcert me, fascinate me." True to her words, The Beaches Of Agnès is a densely populated film, and except Demy (whose death has clearly left Varda with a great void), no one is really privileged over anyone else. She insists upon introducing her crew, reflecting their faces directly into the camera as they construct a set of mirrors on the sand; they are as important to the film as the unexpected and eyebrow-raising images of such global superstars as Harrison Ford and Jim Morrison, captured during Varda’s time working amongst the American counterculture and independent film movement of the late sixties and early seventies. As an aside she mentions how she and Morrison visited the set of Demy’s 1970 fantasy film Donkey Skin. How can you not be amazed by the sight of the two of them lying on the grass, watching Catherine Deneuve perform in full medieval princess costume? But Varda whisks us away fast from this unlikely scene: "End of digression," she understates.

Yet Varda’s is a cinema of digression. The audience’s attention is always tempted away by her plays with perspective, multi-formatting and multimedia, and most importantly, by the words and actions of the characters. By her deft editing techniques, she shows us how each face onscreen belongs to a multitude of other stories and issues. She’ll interview someone for one reason and then include footage of something which shows them in a totally different light, just because it happened to catch her interest. But the films march on as restlessly as their director, gathering more and more, gently and comically undermining their own private dramas, even when such dramas are deeply serious. Perhaps that’s what she’s been portraying all along, the incidental characters in life and life itself’s incidental character.

After previewing all four works to be screened over the Sheffield Doc/Fest’s long weekend, I’m struck by the great but unlikely sense of continuity between them. Or perhaps it’s more of an accumulation. It’s a joy to see the influence of one film, one thought process, within the next film in the chronology. Between Cléo… and Vagabond Varda has deepened her investment in feminism and sharpened her indignation, and in Beaches… it is revealed that Gleaners… handheld close-ups of heart-shaped potatoes eventually become part of a multimedia exhibition including further footage, a pile of real potatoes, and Varda herself dressed as a potato wandering around the exhibition, reciting a list of potato varieties. (Of all directors, surely only Terry Gilliam has dressed up quite so foolishly to perform.) Her curiosity is so infectious that it seems to appeal to others too – collaborators or curators who help to keep her work in an ongoing state of reinvention, re-presentation and reinvigoration. The final shot of The Beaches Of Agnes is of her, seated on a pile of film canisters, the only furniture in a transparent house made of the original negatives of her 1966 film The Creatures, pondering the fundamentals of cinema itself: light and colour.

Sheffield Doc/Fest’s Agnès Varda retrospective begns tomorrow. For more information on the retrospective and the festival itself visit Doc/Fest’s website