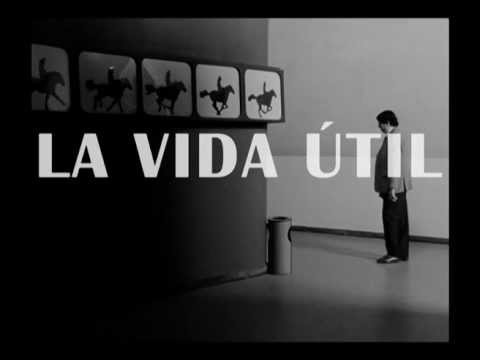

Dictaphone tape players, film reels, postage parcels, projector machines: A Useful Life (La vida útil) places analogue in close-up. Shot in black and white, it speaks to the natural crackles of voice recording and to the graininess of well-played celluloid. It speaks to the film buff and the aesthete; for a time when art house cinema was prized and allowed to thrive.

A Useful Life is a film about a cinephile by trade and by nature – the director of a fading art house cinema in Montevideo, played by real-life Uruguayan critic, Jorge Jellinek. Though a fictional documentary – Frederico Veiroj’s second feature – the Cinemateca Uruguaya does, in real life, face financial difficulties. "We won’t be able to support the institution," learns Jorge, at the film’s half time, "as we can’t support cultural institutions that are not profitable". Sound familiar?

A Useful Life is just the latest in a wave of homages to cinema and its changing forms. The Artist told of the coming of sound to Hollywood, a transition from silent film to ‘talkies’ that for some represented a threatening cacophony. Super 8 celebrated the eponymous, now defunct, Kodak format, while Scorsese’s Hugo depicted the technical innovations of 19th century Frenchman Georges Méliès through the 21st century wonders of 3D. All summon the ‘magic’ that the movies might conjure; more than laying flowers at the grave of a medium about to decay, such films bear witness to the value of cinematic creation, to this day.

Following the details of Jorge’s quotidian routine, A Useful Life begins at an ambulatory pace and sings its song to celluloid in little over an hour. We observe the selection of film programmes, accompany the recording of his weekly radio programme, sit in on the cinema’s trying administrative meetings, peer over the projectionist’s shoulder. For the duration of the film’s first half, we frequent the 1950s architecture of the Cinemateca with Jorge as though it were our regular haunt.

But when Jorge learns that the establishment must close, he is forced to face life outside. He packs up his affairs to a lamenting song-poem by Uruguayan musician Leo Masliah, catches a bus through the city and weeps into a handkerchief. Taciturn and round-stomached, a characteristically charismatic protagonist Jorge is not. And nor is he meant to be: all elegance and beauty is projected onto the medium of film itself.

Even as Jorge tries to reclaim his life, courting a long-standing love interest, Paola, it is the romance of film to which he remains attached. “Find your soulmate, join the cinema”, he had previously endorsed on his radio show. Now, he waits for Paola on the steps of the university where she teaches, practising an impromptu dance, which recalls James Cagney’s scene at the White House in Yankee Doodle Dandy. Of course, his next and final move is to ask Paola to the cinema. “Now?” she asks, “Yes, now,” he replies, and they trot nervously off to watch a movie.

A Useful Life is as much about the magic of cinema as its materiality: the blurred lights and constant whir of the projector – and the responsibility of its operator – are repeatedly brought to the fore. Voicing concerns as to the practicality of moving image formats, from 16mm to DVD, the film is the product of times in which we seek comfort in looking back and in venerating the cinema of the past.

In 2011, Tacita Dean’s ‘Film’ in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall was another paean to the physicality of film. During the making of the installation, the Soho Film Lab, where Dean sourced the 16mm film for her past work, announced that it was closing. ‘Film’ thus mourned the passing of obsolete formats, using 35mm and an upturned cinematoscope projector to stretch images to fit the celluloid borders of the Turbine’s vertical screens. Here is film – was Dean’s primary-coloured cry – and these are film’s techniques: cutting and splicing, delicate hand painting, the layering of images and the rhythm of juxtaposition. Visit the current exhibition of filmmaker, Lis Rhodes, whose work dates back to the ’70s, meanwhile, and you’ll witness further statements for the materiality of film and the cogs that turn in its making.

As other media are dismantled and reassembled according to digital forms, odes to the material abound. For the printed press, Page One: Inside The New York Times, was a compelling insight into the workings of the newspaper as it adjusted to the speed of digital and the immediacy of online reporting. Scenes of newspapers coming off the presses show a behind-the-scenes making that is mechanically familiar. Linotype: The Film presents further machine love, depicting the object that revolutionised printing at its invention in 1886, from hand-assembled words to mechanised "lines-o-type". Before either of these two, a short, Farewell, Etaoin Shrdlu (1980, 16mm), documented the last edition of the New York Times to be printed with linotype – or "hot type", as it was also known – before the switch to ‘cold’ computerised technologies.

Youtube and Vimeos of book porn are rife; page turning is praised; and the texture of paper is relayed into the algorithmic standards of digital design. Physical presence is reassuring; digital movements are fleeting; only, as information and interfaces speed by, things are never this simple.

While A Useful Life’s concerns are timely, then, its aesthetics are out-of-time, antiquated. Within the walls of the Cinemateca, surrounded by art deco-style typography and retro film posters, Jorge could be in living in a different era. But as he hits the bustling streets of Montevideo, signs of the digital present shine through. An advert for a smartphone intrudes upon Veiroj’s black and white veneer, and I’m led to wonder: how far is his choice to shoot in centuries-old monochrome from the predilection of mobile phone photo takers to wash their shots in sepia? Witness the instagramania of the internet. As much as we mourn the obsolescence of formats once loved, we also resuscitate their effects, imposing false patina to see through rose-tinted specs. Of course, Veiroj is really filming upon film, his stylised frames are not digital effect. Yet the aesthetics of A Useful Life belong in some sense to the same sentiment: that is, make life, make film, look old and familiar – make it look better.

The death of cinema is not nearly nigh, yet the film rolls a little like an accompaniment to the medium’s premature funeral. A Useful Life may aspire to the classics, but it doesn’t place much hope in the future.