Image taken from Stan Brackhage’s Mothlite

The news that Soho Film Lab – the last professional lab in the country to be printing 16mm film – had been told by their new owners, Deluxe, that this format is no longer commercially viable and that they should cease printing with immediate effect, is yet another example of the ham-fisted rule of digital technology.

Digital’s rise feels insidious and all-too powerful; like watching an abscess at work. Both the nature of its wild success and the crisp images it conveys so ‘realistically’ are unforgiving. Try and hide, it seems to say; we’ll get you in the end, you’ll ‘see’.

Maybe’s it’s the fact that I grew up watching so much TV and cinema, shot in 16mm or 35mm, and shown on traditional screens; either weighty, wood-backed tellys that curved forward acrobatically, or cinema screens that wavered like white sheets hung out to dry. Nothing comes close to the poetry of the muddied images screened within these old-fashioned or soon-to-be-obsolete squares. My eyes have yet to adjust to flat-screens; which seem to have developed in tandem with flat cinematography and flat writing. No mystery. No hiding. No surprise. No shots in the dark.

Having recently finished shooting a micro-budget film using a High Definition Canon 5.D camera, this is not an old hat rant concerned with personal preferences. I won’t contest that 16mm images are better, or more enthralling, or captivating than anything captured on digital. Both serve a quite brilliant and beautiful purpose in their own unique right (and in the right hands) and the origins of both are not too dissimilar: 16mm was originally a cheaper alternative to the more luxurious 35mm; and digital cameras are a continuation of this thread.

There’s a definite place for both. The point is not to eradicate, or replace any of these portals and film stocks – whether that’s a wonky telly or some potentially life-changing piece of 16mm film stock. The decision should be for us – the consumer – to make.

Unfortunately, the reasoning behind this recent news makes reasonable business sense: in short, the cinema industry has no need for 16mm anymore. 35mm will continue to be processed, but the artists and film-makers who favoured its less than half-sized, lower-priced celluloid sibling, may well have to seek alternatives. The artist, Tacita Dean, has already written a valuable piece on this harsh dilemma.

Tacita Dean, The Green Ray

It seems as if we’re in danger of advancing without developing. The reality of having to ‘go digital’ at the expense of your old goggle-box is mystifying. The content of the TV remains largely the same; third-rate and in debt to the savvy pull of American writing talent; but the square has changed. The square is in thrall to a demented light that casts clarity over and above content. Same un-romantic deal with e-books: to degrade the artistry of 16mm film stock, and tangible books with illustrative covers and pages that will in time stain with age and carry the smell of years and people within their hard-backs and soft-backs (these descriptive words alone allude to a sense of humanity that sounds woefully contrived when replaced with the unkind and adolescent ‘Kindle’), seems, at best, unnecessary, and at the very worst dangerous. The inherent plasticity of it all suggests a violent eradication of our very selves.

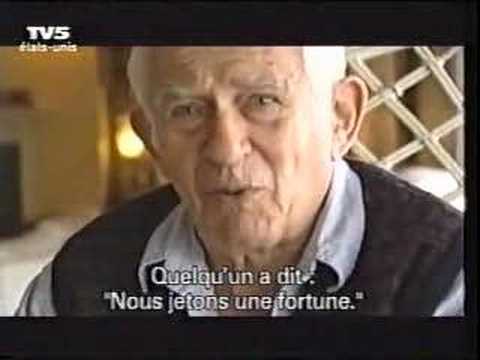

A few years before his death, Norman Mailer talked at length, and with customary skill and tenacity about the dangers implicit in this ‘plastic’ culture; how there is no hopeful feeling to this reduced material; and how it may well have a direct link to various states of frustrated violence.

There can be few sentiments more debilitating and restrictive than revering the good old, dark old days, but something about our lax embrace of digital technology and the cheap waste it’s made from, may, in time, have us wondering and bemoaning the final days of our future past.

To try and save 16mm in the UK click here.

Austin Collings’ debut feature with Brollywood Productions, Nocturnes, is currently in post-production