As the world falls apart around us, all we can do is sit indoors and wait for the apocalypse to hurry up and get on with it. This was surely not how it was meant to be – instead of strapping some kind of weapon to my back, mounting an SUV and cruising the barren remnants of civilisation, I’m spending even more time than usual in front of a TV screen. I’m sure I wasn’t alone in imagining once-in-a-generation events to be a little more, well, exciting.

And until new films are back in cinemas, we’ve no choice but to watch old ones. In my meandering through decades gone by, I find myself longing for a time when it was ideas, not viruses, that crossed cultural boundaries and spread around the world. A time when the world was stimulated, not stalled, by travel, connectivity, and the mingling of people from faraway places.

A time like the 1960s – the rush of the jet age, when the increasing prevalence of flying made the world suddenly smaller. This coalesced with the ground-up reconception of the film industry at the time, and caused an exchange of styles more rapid and revolutionary than any other period in history.

Hollywood’s Golden Age was coming to an end. For the new youth, Old Hollywood was stuffy, tame, and lacking thrills. The conservative moral rules of the Hays Code were being increasingly bent, broken, or simply ignored by increasingly liberal filmmakers and audiences. Independent films were on the rise, and it was becoming financially viable to produce what had been hitherto unheard of: a low-budget, spectacle-driven film.

Leading the way were the Spaghetti Westerns, beginning in earnest with Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars in 1964. While the setting may have been the Wild West, the plot was lifted from the Far East: upon its release, Akira Kurosawa would successfully sue Leone for the wholesale theft of his Yojimbo script (the lawsuit ended up delaying the film’s US release to 1967). In style, too, the film combined John Ford’s expansive American vistas (at their most dynamic in Stagecoach and their most poignant in The Searchers) with Kurosawa’s operatic Japanese storytelling. In just one film, Leone illustrated the possibilities of merging vastly different cinematic traditions. The Japanese samurai film, the American western, and the European exploitation film came together; the result offered was a pivotal moment in the history of action films.

A Fistful of Dollars isn’t the greatest Spaghetti Western, but its influence is. Later films eclipsed its achievements: For a Few Dollars More is more emotionally satisfying; The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is grander in scope; Django is leaner and meaner and The Great Silence is bolder and smarter. But none of those would exist without the smash hit success of A Fistful of Dollars.

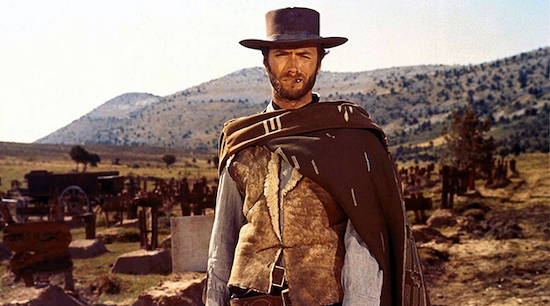

It cemented into mythology the lone, laconic, morally dubious gunslinger, played here by Clint Eastwood in a role he would come back to again and again. More generally, Fistful and its offspring proved once and for all that the days of good guys and bad guys, the “cowboys and injuns” of the Western myth as written over and over in American pop culture, were over – most of the time, the heroes racked up higher bodycounts than the villains. It was clear the Italians were on to something; A Fistful of Dollars was made for only around $200,000, and grossed over $14 million – who wouldn’t want to emulate that?

Over in the Hong Kong film industry (the closest to a Chinese film industry under Mao’s cultural revolution), the Shaw Brothers were the largest production company, but their budgets were still pennies compared to Hollywood. Their wuxia films, a Chinese genre focusing on sweeping romanticism and martial arts, proved adept at absorbing some of the techniques that worked so well in Italy: vigorous visual styles, substantial bloody violence, lawless landscapes and lone heroes. But despite the bloodshed, a Buddhist spirituality propels the finest of these films, particularly by director King Hu. Come Drink With Me cast a ballerina in its lead role, giving the combat a poetical, dance-like kinetic quality, and his grandest work, A Touch of Zen, is meditative, wistful, and bursting with nature.

Despite wuxia’s enduring legacy, these historical films wouldn’t set alight the rowdy, politically active youth. In the turbulent political context of the 1960s, the people of Hong Kong needed to express their indignation and fury; to assert the power of Chinese culture against the dominant foreign forces from Japan, Britain and America. They needed kung fu.

An ancient Chinese tradition of self-defence, kung fu was the ideal mode of expression for Hong Kong’s contemporary youth embittered by foreign occupation and fuelled by Chinese nationalism. So, when Bruce Lee burst onto the scene in 1971, it sparked a kung fu revolution.

For the people of Hong Kong, Bruce Lee was a Chinese-nationalist hero. The narratives of films like Fist of Fury are blatantly anti-Japanese, and even his use of nunchaku was a political choice: the weapons were originally made from everyday fishing tools, designed to allow the lower classes to construct their own defences against the katanas of the ruling Japanese. Thorny regional geopolitics aside, his movements possess an otherworldly fluidity and power, whether he’s flipping nunchaku, kicking his way through a crowd of combatants, or just plain punching someone to death. Who doesn’t get chills seeing Lee, stripped to the waist, looking somewhere between ballet dancer and wild beast, poised to thwart any and all attacks using any and all of his limbs?

Ironically, Lee encapsulates better than anyone the fruitful internationalism of the period. Shunned as a teen for his dual Chinese and German ancestry, he moved to the US after a street fight with a suspected gangster. It was in America that he developed his revolutionary kung fu style (Jeet Kune Do) and achieved some TV success as sidekick Kato in The Green Hornet. But after his failed attempt to launch his own show, a broke Lee returned to Hong Kong. Unbeknownst to him, The Green Hornet had made him famous there, where it was commonly referred to as “The Kato Show”. He used his star power to pioneer the Kung Fu film, rocketing his profile to astronomical levels across the world.

Bruce Lee thus embodied a bridge between East and West: star of American TV popular in Hong Kong, and star of Hong Kong cinema popular in America. His films were clearly informed by the Spaghetti Westerns (down to the copycat Morricone scores), but the martial arts on display remain singularly spectacular. Performance and politics were added to the modus operandi of action films.

Lee’s first two films were also made for a meagre $100,000 each. Eager to produce similar successes by mirroring the force, excitement and political potency of these Kung Fu films, small Japanese studios began to produce cheap, bloody exploitation films of their own.

But these low-budget Japanese exploitation films were not only informed by the Spaghetti Westerns of Italy and the Kung Fu films of Hong Kong; they also pushed the envelope of action films even further. Formally inventive in story and style, films like the gorgeous, furious Lady Snowblood and the pitiless Lone Wolf and Cub series (both based on Kazuo Koike manga) experimented with quick cutting, flashbacks upon flashbacks, and poetic imagery – all without losing the appeal of a full-bore, bloody action film.

These film’s aesthetic innovations alone would be felt for decades to come. They proliferated a cartoonish action style – bright red blood, extreme closeups of eyes, crash zooms – informed by Spaghetti Westerns and Kung Fu films, but also by manga (which, ironically, was itself inspired by film). The crash zoom is a perfect example: zoom lenses, developed throughout the 1950s, were all the rage as low-budget filmmakers were finding it cheaper to shoot longer zooming takes than to cut to closeups. Directors trying to cheaply emulate a movement between manga panels (a wide shot followed by a closeup) would naturally just zoom in as fast as possible. Now, crash zooms are such an action staple as to be parodic.

The successes of all these small international films had far-reaching effects in wider cinema too. Dirty Harry has the six-shooters, bloody showdowns and fuzzy morality worthy of any Wild Italian West, and the Mad Max films infuse the visual approach of the Spaghettis with adrenaline and engine oil. John Woo took Kung Fu films and added shedloads of explosive ammunition, creating the “heroic bloodshed” genre, which would later become the new norm for Hollywood action films. The beautiful, soaring combat of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon is inspired by King Hu’s wuxia style. Kill Bill’s plot and visuals were heavily inspired by (ripped off from?) Lady Snowblood. The Raid films critique the corruption of Indonesian government with a fury that would make Bruce Lee proud, and the John Wick films, with their “gun fu”, are another extension of the performance-based action Lee pioneered. And any time anyone swings a katana for dramatic effect, spare a thought for Itto Ogami and his son at the crossroads of Hell.

All of this cultural exchange happened within the space of one ten-year frenzy. The jet age sent ideas and styles flying around the world, and low-budget international filmmakers exploited low costs and thrill-seeking audiences, learning and stealing from each other, to great success. The modern action film was born, and cinema was forever changed. Away from the mainstream sanitisation of Hollywood, the daring styles and politics of these films could be truly dangerous.

The impact stretches further than just film. The Wu-Tang Clan derive their name from the Shaw Brothers’ 1970s wuxia films, and frequently sample their American dubs (films like The 36th Chamber of Shaolin). GZA’s classic 1995 record Liquid Swords gets most of its eerie vocal samples from Shogun Assassin, an abridged, dubbed version of the first two Lone Wolf and Cub films which was released in America and Britain in 1980. Violent, lawless anime like Afro Samurai and Samurai Champloo owe everything to vengeance tales like Lady Snowblood.

The world needs such a global mingling of ideas to challenge established orders and develop new aesthetics, replacing outmoded traditions with contemporary bite. When all this is over, I hope for another surge in connectivity; a renewed desire to learn from the rest of the world; a return to innovating through emulating. The effects could be revolutionary.