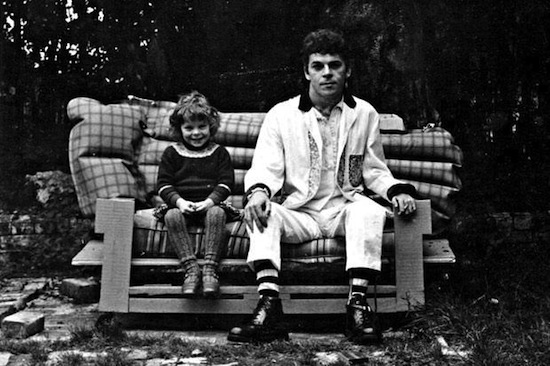

Hallo Sausages is titled thus in tribute to the only two words Ian Dury wrote in a Word document on his new laptop, given to him by his family, when he expressed a desire to work on ideas for his autobiography not long before he died of cancer in 2000, aged just 57.

Dury had previously struggled with the idea of writing his memoirs. He couldn’t guarantee that he could, or would, give us the full story anyway, for fear of hurting his beloved relatives, and embarrassing his children. But, in a way, an autobiography of sorts was already in existence thanks to Dury’s lyrics – rich with hints, impressions, satires and sharp-focus details of his life and what affected him over the years. They were just waiting to be collected, smoothed out, lovingly put in order. As Dury himself scribbled, they were ‘lyrical scraps, looking for a home. One day.’

Well, one day, Dury’s eldest child Jemima did decide to root through everything she could find that her father had stored away: photographs, papers, an “inventory of his life”, which also, crucially, included lyrics; scribbled, typed, yellowing, coffee-stained, brilliant lyrics.

Through these, we are permitted a precious glimpse through the curtains, the fabled fourth wall is temporarily dissolved, and, as the words lie before us on the pages of this visually beautiful book, as opposed to being fired at us in the form of a song, we can contemplate them in a different way. So, we need look no further to get to the heart of this complex man, who clearly had great heart and felt emotions deeply despite an intimidating, often callous veneer.

The book includes many items that have never been publicly seen up to now, and each new era of lyrics opens with an often touching and revealing portrait of that time written by Jemima herself. The package also includes a CD of “as many demos as possible”, and is dedicated, of course, to Jemima’s family.

The Blockheads’ circle of loved ones – which includes contributors Sir Peter Blake (‘Peter The Painter’); Dury’s widow, the artist Sophy Tilson; former Kilburn cohort Humphrey Ocean and, posthumously, Barney Bubbles – is an institution in itself, so it makes perfect sense that this special book is also very much a family affair. At times the reader feels quite honoured to be allowed to see certain very personal and clearly treasured inclusions in the book, not least an image of a Victorian-style sampler embroidered by Jemima and given to her dad for Christmas in 1978. Perfectly stitched is the ‘Sweet Gene Vincent’ lyric: ‘Shall I mourn your decline with some Thunderbird wine…’

The entire book, which bears the pattern of Dury’s signature silk scarf on the inside covers, shines with bohemian, homespun charm, and a very Dury combination of proto-punk DIY / arts and crafts slant. It is, perhaps, also a reflection of the interesting cultural conflict within the man himself between his carefully cultivated ‘rough diamond’ image and working class affiliations, and his erudite, educated, free-thinking art school creativity.

Part of the beauty of this book is that many lyric sheets have been included simply as they were found – typed, crumpled, scribbled on, corrected – and so we can see the secrets, the working notes, the lyrics that got away. We are granted a glimpse of the process as lines have been typed and then scribbled through, still visible, or camouflaged with a row of typed ‘X’s. (For example, we get to see that, while writing lyrics to the song ‘Father’, Dury toyed between choosing the line ‘Flaming load of twats’ and ‘bleeding bloody berks’ before opting for the latter, and that ‘the buttons on your nightie are getting on my nelly’ was chosen over the rejected line ‘the buttons on your nightie are sticking in my dubrey’. We also learn, thanks to a note scribbled on the bottom of the yellowing page, that Dury needed an ‘alphabetted [sic] notebook, Woolworths, 10p.’)

As is displayed here, Dury’s lyrics very much stand alone as poems, from the sweet and heartfelt (‘The Boy On The Bridge’) to the jagged and powerfully evocative (‘Sweet Gene Vincent’, ‘The Ghost Of Rock And Roll’) and to the almost blessing-like quality of songs like ‘Will’O The Wisp’ and ‘You’re The Why’. He might have preferred the more workmanlike quality of the tag ‘wordsmith’, but he was very much a poet, and, often, a romantic. ‘Wordsmith’ neatly plays down the magic, but we swiftly discover it for ourselves, and take it to our hearts, all the same.

Other jewels within these pages include a list of possible band names, typed out just before Ian settled on christening his motley crew of musicians with the title Kilburn and the High Roads, on the cusp of the 1970s. The list includes such contenders as Chutney, England’s Glory, The Tights and Nervous Piss, not to mention my personal favourite, Cuthbert and the Cunts. Potential radio-play clearly wasn’t at the forefront of Dury’s mind when he was brainstorming.

A flurry of slogans, typed in capitals, for Stiff Records is another unexpected pleasure: including the classic ‘Bottle In Front Of Me Or A Frontal Lobotomy…’, and ideas such as ‘Stiff: Where Nutters Count, Where Walls Wear Wellingtons, Where Quality Is A Problem… ‘

Meanwhile a scrapbooky collection of phrases collected for future use is just pure Dury heaven: "When she takes her bra off she looks like Boris Karloff…’ ‘Sylvia Salad would it be valid to sing you a ballad?’. But from the sublime and cheeky wordplay we suddenly find ourselves amid provocative and vaguely sinister pathos: ‘my eyes are so dark, my lips are so clever, why don’t you love me?’ ‘I’m the author of my own misfortune, don’t need a ghostwriter.’ And then there’s the nervous laugh-inducing: ‘I’ve only killed one lady…’

We are treated to naughty seaside postcard humour, (‘She’s got crinkly hair underneath her underwear / I know because I’ve been there’), and then, ah, then we are confronted with the lyrics to ‘Reasons To Be Cheerful’. This, my friends, really is England’s glory, a true joy, a treasure. Reading the ‘Reasons’ lyric is, for many of us, like coming home. In fact, it’s better than that, it’s like coming home to someone who’s always happy to see you. It’s like getting back into bed.

There’s a rare flutter of melancholy romance in ‘That’s Not All’ (‘I’ll love you ‘til the cows come home, that’s not all I want to say’) and rare heart-bursting idealism in ‘You’ll See Glimpses’. Dury didn’t just insert phrases effortlessly into our everyday vernacular, (‘Sex and Drugs and Rock and Roll’, ‘Reasons…’) he could break your heart, bruise it, lift it, mend it.

Part of Dury’s unparalleled strength lyrically was his ability to play with both humour and menace. His first lyric, to ‘I Made Mary Cry’ is deliberately shocking (‘severed a ham-string in the lonely bus shelter…’) while the words to ‘If I Was With A Woman’ are insecure and vindictive, chilling, pure dark theatre: "If I was with a woman, I’d threaten to unload her every time she asked me to explain…’ But cleverly, perceptively, Dury reveals quite openly the fear and hurt beneath the hate in the final verse: ‘I was with a woman, she took away my spirit, no woman’s coming close to me again.’ A song’s worth of bile aside, you suddenly find yourself feeling a kind of pity for this sad, bitter protagonist. (Although unfortunately some not so enlightened fans get rather excited by this song, as if it gives a kind of license to being a misogynist. Fellas, this is not an instruction manual.)

Another great skill of Dury’s was of course his gift for creating poetry to fit the most unpoetic of situations… from the fragrantly elegant line ‘the finest grains for my lady’s veins…’ from the expletive-rich ‘Plaistow Patricia’ to the wry balance of delicacy and brutality and over-the fence-gossipy scandal of ‘This Is What We Find’: ‘Home improvement expert Harold Hill of Harold Hill / Of do-it-yourself dexterity and double-glazing skill / Came home to find another gentleman’s kippers in the grill / So sanded off his winkle with his Black and Decker drill…’

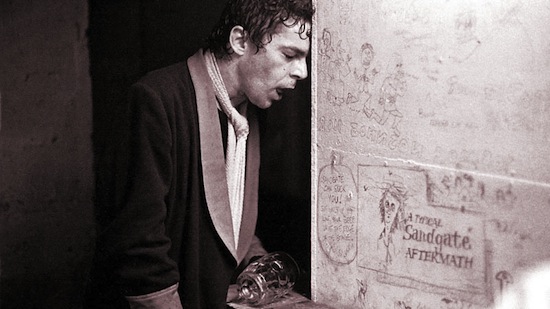

Whether raw and emotional, bitingly sarcastic or downright dark, the facets of Dury’s personality are revealed unflinchingly here, and not just in constructed characters and theatrical cartoony figures but also in stories and interpretations of figures close to Dury’s heart, written simply and lovingly. ‘My Old Man’ is a touching portrait of his father William, and ‘Thank You, Mum’, well, you’d have to be pretty hard-hearted not to mist up during that one. There are nods to his institutionalised childhood in the switchblade-flashing ‘I Made Mary Cry’ (‘I’ll dream my dreams in a cold iron bed, fourteen more days in a white dormitory’), and to his teenage greaser memories within ‘Upminster Kid. ‘Grape and Grain’ sees an honest contemplation of his drinking, and Dury’s emotions are laid bare in the emotional ‘Tell The Children’ after he divorced their mother Betty (Jemima wasn’t even aware of this song for many years).

In ‘Okay Roland’, we are invited to share the thrill of meeting Dury’s hero, the jazz saxophonist Roland Kirk (‘the warmest hands in all the land are shaking hands with me’) at Ronnie Scott’s, a place Dury loved. Indeed, his love for London and Essex, his unwavering muses, dances through every song, whether in blatant tribute, in ‘The Bus Driver’s Prayer’ or simply through the sharp wordplay, rhyming slang and flashes of Polari (hip pidgeon Italian / Romany hybrid used in the 50s and 60s particularly within the gay community) that pepper the songs.

Jemima says that her father’s use of ‘industrial language’ was more sparing than people imagine, but when he used it, it was there for a reason. Jemima recalls hearing Ian sing the reprise of the title of ‘Fucking Ada’ over and over again, roaring it out; Jemima describes it as if her father, then in the grip of an addiction to Mogadon, was dredging “all the crap out of his system.”

In years to come, after being diagnosed with cancer in the 1990s, there is, understandably, something of a shift in Dury’s lyrics, and we are privy to his new outlook on life, love and family in songs such as ‘The Passing Show’, ‘You’re My Baby’ and ‘One Love’. Put simply, the essence of Dury’s life is mapped out here, in all its vibrant transience, in the pages of this book. Some lyrics may be sprinkled with a little poetic licence, but probably not that much.

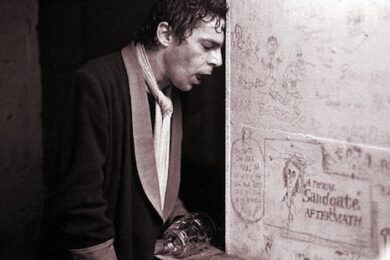

As a father, it’s not news that Dury wasn’t there as much as he could have been, often leaving his children in the hands of a psychedelic roadie who went by the name of the Sulphate Strangler(quite mad but benevolent, we are assured). But despite this, what Jemima and son Baxter thought of what he was doing clearly meant a great deal to him. Jemima was, in Dury’s eyes, his greatest critic, and he would frequently be what he called ‘daughterised’ when she felt the need to speak up.

Once more, Jemima has found herself ‘daughterising’, in a way, by collating this book; tidying up for him, sorting everything out, being the organised one. Ultimately, this project must have been, surely, a hugely emotional process, but Jemima has come through it having preserved her father’s precious legacy in a way that he himself would be utterly captivated by. It glows with love and care.

As Dury’s first-born rather touchingly put it: “I used to put his records back in their sleeves when I was a kid and tidy up his desk, and I guess I’ve done that all over again.”

Zoë Howe will be interviewing Jemima Dury at the Essex Book Festival on March 18th.

Hallo Sausages – The Lyrics Of Ian Dury is available now, published by Bloomsbury

Follow @theQuietusBooks on Twitter for more