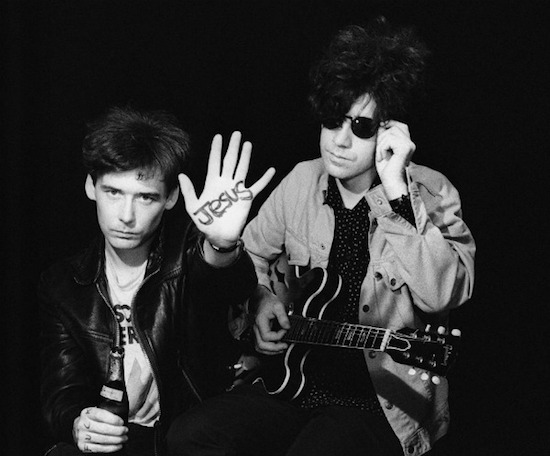

Instantly drawn to the imperious red and black image of the Reid brothers that adorns the record sleeve, it was the frenetic, hazy dissonance of the Jesus and Mary Chain’s Psychocandy that cultivated me, discovering a new-found reverence for music during one of my formative moments in life. The copy of Smash Hits I’d rush to my local newsagents for every week was soon replaced by the seemingly cooler, more rebellious NME. Having never really lived through it in real time (I was barely 5 months old when Automatic came out in October 1989) I get the usual “you had to be there” retort from those that were lucky enough to have witnessed it all.

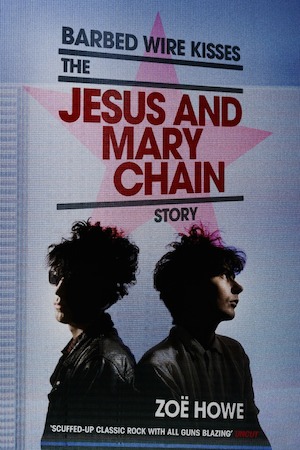

And in an era which thrives on our proclivity for the past, it would be easy to denounce the Mary Chain for cashing in on the perpetual stream of 80s nostalgia: the news of a brief tour which will see the band play Psychocandy in full in November was announced only last week, suitably followed by the news that Alan McGee would revive Creation management and sign the Mary Chain once more. But in Barbed Wire Kisses, the new and long-awaited biography of the Jesus and Mary Chain, Zoe Howe echoes a sentiment that I’ve always reiterated myself: this band are every bit as vital and relevant today, and though they’ve never been averse to striving for mainstream success – and certainly never discouraged by fame – the Mary Chain remained defiantly anti-celebrity, staying true to themselves during an era of excess, and as Howe rightly identifies, ‘in a current culture of disposability, short attention spans and cynical TV ‘talent shows, it’s arguable we need them even more.’

Barbed Wire Kisses chronicles the Mary Chain’s trajectory with amusing, anecdotal first-hand accounts from Jim Reid, Douglas Hart, Alan McGee, Bobby Gillespie (who in particular, proves to be an important proponent of the JAMC) and other important associates of the Mary Chain tribe. It begins with the early days of their inception as two brothers, William and Jim Reid, living in the less than inspiring, humdrum surroundings of Scotland’s first new town East Kilbride. Holed up in their bedrooms, they would obsess over music, TV and books. It tracks the primal years of their notoriously raucous and disorderly live shows where they would be kicked off stage not long after they started playing, along with the making of 6 albums and everything that happened in-between; the touring, the perpetual line-up changes and the sporadically volatile relationship between the only sole constants William and Jim.

Barbed Wire Kisses alludes to their anti-social behaviour quite frequently; despite the Mary Chain’s musical sphere shifting marginally over time, the Reid brother’s shyness remained unchanged, and is a key in understanding the band’s renowned contrariness. The book frequents this notion that everything about the Mary Chain is pleasingly contradictive; even the Reid brothers themselves, however musically congruent, became somewhat of the antithesis of each other. Of course, the annals of rock n roll has a long history of quarrelling brothers, but it’s the Mary Chain’s story that stands the test of time. Despite the regularly cited, notorious drunkenness, their story, as depicted here, is one that is primarily about the music, two brothers’ love for music and writing and creating it. Their predilection for pop-stardom contradicted by their abhorrence for everything that came with it is a recurring theme. They so readily neglected the credible ‘indie’ tag, yet they were averse to the trappings that came with their preference for TOTP appearances and Smash Hits covers, reviling interviews and avoiding them at all costs. The central theme of Barbed Wire Kisses is, of course, one that contains many contradictions, but above all else it’s affirmation of the Mary Chain’s bold sense of integrity.

In true Mary Chain style, there’s a witty undertone to Barbed Wire Kisses that permeates throughout every anecdote told by Jim Reid and various other people imperative to the band’s history. None more so than the band’s numerous encounters with Paul Weller. On one occasion, Weller advises Jim not to put his hand over the mic so as to prevent any feedback. Indeed, fans of the Mary Chain will know that this was the least of their intentions. What’s most interesting about Barbed Wire Kisses, although perhaps inadvertent, is the interactive aspect of it. It’s not too far into the past enough to alienate younger readers and fans of the band; archival footage is easily accessible, and like another reviewer mentioned, when you read this book you find yourself deviating towards YouTube to re-live the accounts of inebriated TV appearances which, however articulately depicted by Zoe, are well worth witnessing visually.

The music biography as a format often runs the risk of afflicting the reader with exhaustive or biased accounts, resulting in a changed or even negative perception of the artist or band. In this instance, however, the book competently weaves first person interviews with quotes from trusted sources to tell the story from the beginning to what is not quite yet the end. Here, Howe does a fantastic job at unveiling a band that have been, up until now, shrouded in mystery. She takes us back to the Mary Chain’s epoch without omitting anything, and writes about some of the most turbulent, acclaimed times with the same importance as she does when she writes about the band at their most inactive or critically doubted.

What Barbed Wire Kisses perhaps reveals most is, through all of the Reid’s famed squabbling and juxtapositions, there really is no Mary Chain without one or the other – evinced in the accounts given of the band’s eventual collapse in 1999, in which Jim confesses to Uncut‘s Simon Goddard in 2001 that ‘It was bloody awful. We were standing on stage as the Mary Chain, but I looked to my left and that big mop top wasn’t there’. Unfortunately, William declined to make any contributions, but even so, Barbed Wire Kisses is as comprehensively and beautifully wrought as it could ever be.

Barbed Wire Kisses is out now, published by Polygon