Anthony Galluzzo’s short, polished and highly readable Against the Vortex is, among other things, a significant addition to the ongoing reappraisal of the 1970s. Was it merely a dour, crisis and rubbish strewn interregnum between the death of the Swinging Sixties and the rebirth of the Cool Capitalist Eighties or a moment of artistic and social foment in which multiple futures hove into view?

The book uses John Boorman’s film and novel, the sci-fi fantasy Zardoz (due to be re-issued by Repeater books in September this year) as the means through which to explore and orchestrate a new take on the era’s radical potentialities as well as offer a critique of a broad tendency that incorporates a number of overlapping iterations from across the political spectrum: The Californian Ideology, Technological optimism, Transhumanism, Accelerationisms of both left and right. These currents are embodied in the book and film by the Vortex, an enclave of Eternals who live in a Last-Manish state of boredom and are shaken out of their Apollonian inertia by the arrival of Zed, a Brutal from the outlands who has been used as a means to control the surplus populations the Eternals exploit for the labour that maintains their lifestyles.

There are of course a number of potential readings of this scenario and the dynamic between a cosseted elite at the centre and impoverished hordes on the periphery. Galluzzo deploys, or at least gestures at several familiar devices in the theorist’s arsenal – colonialism, biopolitics, World Systems Theory among others – but is really more interested in using Boorman’s dissatisfaction with the intentional communities he explored in the 60s along with his scepticism around an emergent techno-solutionism to explore what we might call the subjective, existential foundation for a politics of degrowth.

Degrowth is a complex and contested field that draws on any number of schools of thought and traditions, many of whose advocates disagree over what the term actually means. Is it simply de-centring GDP as the summum bonum of political life and replacing it with other measures of wellbeing or, as its antagonists would claim, a rejection of modernity itself, expressive of a self-abnegating desire to return to a wattle and daub smeared world of acoustic guitars and undercooked root vegetables gnawed around the village campfire?

Can socialist and Marxist ideals – traditionally “productivist” and interested in increasing access to material goods for all-indeed posited in some schools on the idea that once the artificial scarcity imposed by capitalism is removed, we will drown in the Red Plenty of a Luxury Communism – be squared with concerns around the finiteness and increasing precarity of the earth’s resources?

Galluzzo’s use of the term suggests something like the planned reduction of energy use and consumption, primarily in the developed (or overdeveloped) world as a way of bringing those countries back into internal realignment with ecological limits as well as with the countries of the global south – a kind of reallocation of energy and inputs at a global level with an eye to achieving homeostasis and thereby, though the book steers clear of any wokeisms, environmental justice.

The book itself is part of a short collection on the theme of Utopia and Galluzzo proposes, in contrast to the promised communist abundance of Teslas For All!, a Utopia of Limits. In one sense this is an attempt to reintegrate or rebalance the utopian impulse away from ideas of transformation via technology and the now somewhat shopworn panoply of extropian and transhumanist imagery and narratives and emphasise a different type of hybridity – not the man-machine or mutant but the centaur-man, always-already bound up in its creatureliness and interdependence with the natural world. It is in letting go of fantasies of eternal life, technological transformation and apartness from nature, and accepting, even embracing death as a ‘gift’ that we can reorient ourselves toward each other and the larger world of which we are a part.

It might be better to say then that to an extent Galluzzo proposes Utopia as Limit (or the reverse, Limit as Utopia) and that it’s precisely the drive toward an unachievable, phantasmatic transcendence via accumulation, the corollary of capital’s own blind, ultimately endless drive to turn money into more money via our work and consumption that is the source of our unhappiness. In this respect Galluzzo’s work dovetails in some ways with a critic from a rather different tradition, Todd McGowan, whose Capitalism and Desire and Embracing Alienation also look to find ways to deal with the knotty imbrications of desire and the commodity. For Galluzzo, there is, at least implicitly, a solution to modern forms of estrangement and alienation – an acceptance of finitude and a reintegration of the psyche into the planetary web of life – there may be no earthly paradise we can return to, but we can attain at least a form of contemplative and cautious dwelling within the ways we are entangled and circumscribed with and by the natural world.

In proposing a Utopia of Limits, the book draws on an extensive and neglected counter-canon of late 60s thinkers that Galluzzo dubs “Critical Aquarians”: Ivan Illich, Ernest Becker, Norman O Brown and Boorman himself, among others. Galluzzo does a great job of précising some of the central elements of what he considers the relevant aspects of these wide-ranging and prolific thinkers’ work and by drawing on them, as opposed to a more familiar retinue of philosophers and critical theorist, Foucault, Butler, Lacan, Deleuze et al Galluzzo positions himself on one side of the current debate on the left (and elsewhere) around “reality” – for those on the other side of this schism, reality is a code word for a set of authoritarian or reactionary positions that look to limit certain forms of emergence and impose an often-binary framework on a plastic and in-principle illimitable subjectivity.

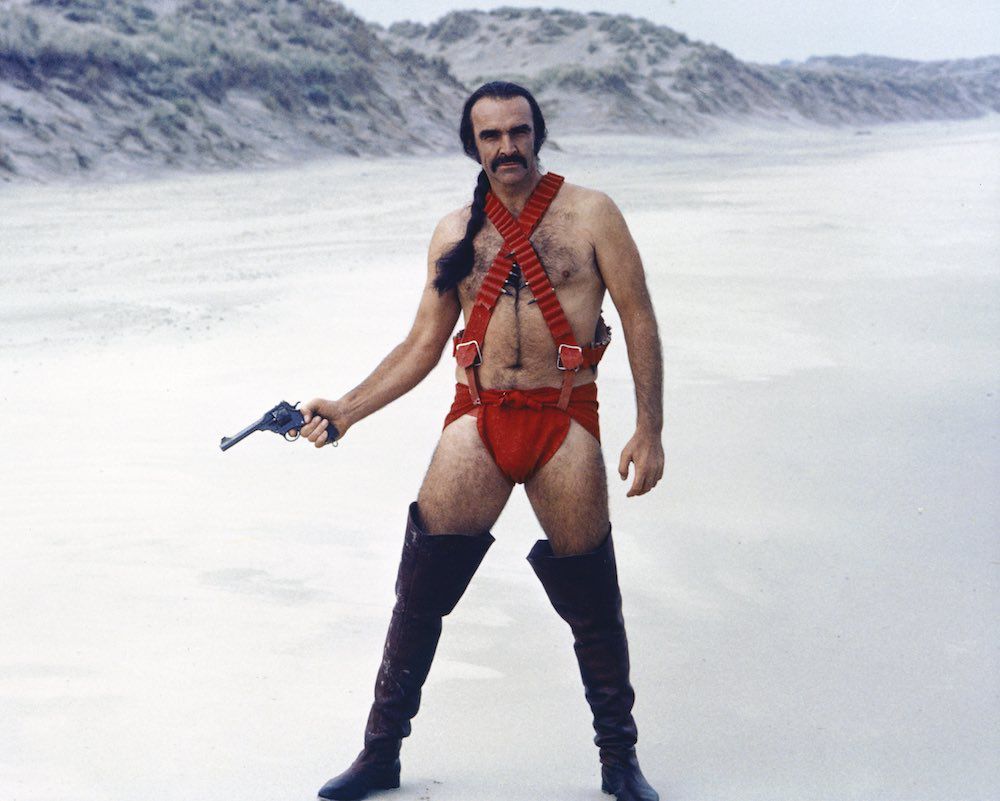

Nonetheless, in a world and a culture overwhelmed by the ongoing tournaments of the attention economy and an academic Leftism in thrall to its logic, Against the Vortex feels, despite its ostensibly camp subject matter, sober and provocative in the best sense. A book that insists along with Kafka that “the meaning of life is that it stops”, we must take our mortality as a given, the ground-zero of our being in the world and work back from there. That it does so through an artful reading of a film and a book that is invariably, though perhaps understandably, overshadowed by the spectacle of James Bond in a scarlet mankini and thigh high boots makes it even more remarkable.

Against The Vortex is published by Zero Books