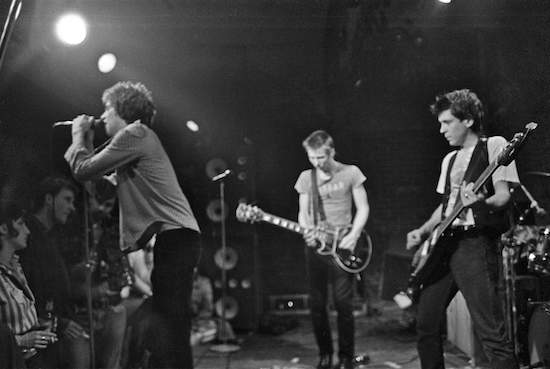

Sleepers. Photo by James Stark

Joann Berman: The thing about San Francisco that made it different from New York and LA was that it came from a visual art background because of the Art Institute.

Ruby Ray: The first Search & Destroy address, 3426 Jones, was an apartment that was right across the street from the Art Institute. There was a total interaction between the Art Institute and the punk scene.

Sally Webster: A lot of people were at the Art Institute. Bruce Pollack, who had another sort of performance space around the corner called the A-Hole. And Sue White. Jill Hoffman from Target Video. I went to the College of Arts and Crafts [in Oakland] for one year, and then we decided San Francisco just seemed better. It was a great school. Great teachers.

Stephen Wymore: David Hockney was teaching there. So was Bruce Conner. It was very inspiring to us because those guys were heavyweights.

Carol Detweiler: It wasn’t very structured, really. It was really pretty open- ended. Some people weren’t even taking classes there, but they would maybe sit in or just sort of infiltrate.

Sally Webster: You could just show up at school and go. You didn’t even have to be enrolled. People would sleep on the ledges of the Art Institute. They’d live in the closets. There was no security, really. And then eventually, if you showed up enough, they’d give you a scholarship and just enrol you. At that point, I think it was $2,000 a year, and I could pay for it working in a movie theatre making popcorn or waitressing. Easily.

Bruce Pollack: I lived at the Art Institute – literally lived at the Art Institute for two years.

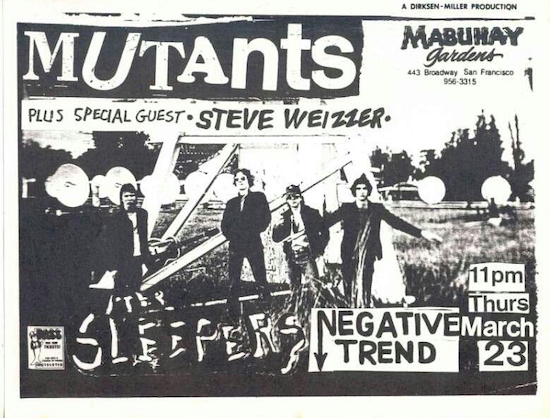

Matt Heckert: I had never really imagined being in a band before. But then I was going to the Art Institute, and then all of a sudden, I was hearing about the Mabuhay Gardens. And, of course, I’m seeing punks around school. I didn’t really know anything about punk before I moved out there. And I went, “What is this about? This is crazy.” We just started to go over to the Mabuhay and see the bands and hang out, and we realised that people were just doing this stuff, and anybody could be in a band.

The other thing about school is that I basically went there for two years, and then I left. In retrospect, I realized that I went there long enough to gain connections into the underground of the city. And once I had that, I didn’t need school anymore.

Located in North Beach within walking distance of City Lights and the Mabuhay, the Art Institute acted as the main conduit between the punk scene and the highbrow art world. For a brief time, those two worlds blurred together, with several bands – including the Mutants, Avengers, and Pink Section – forming thanks to connections made at the SFAI.

At the same time, more credentialed visual artists – not just from the Art Institute but also CCAC and even the for-profit Academy of Art College – found themselves drawn to punk, seeing it as a refuge from the more established art scene. “I totally got into the whole punk thing because it made so much sense,” says Target Video’s Joe Rees, who was teaching at the Academy of Art in those days. “It was an opportunity to do your thing, to live your life being creative. And what was the alternative in those days? Those stinky, stodgy museum shows and all those godawful art openings with that cheap wine. It just was no good.”

Boundaries were being broken, not only between the art world and the live-music scene but also within the art world itself. As filmmaker Craig Baldwin explains, “The San Francisco Art Institute may actually be able to claim it was the first art school that had this – they call it ‘New Genres,’ which is a stupid name because, of course, it’s not new anymore. But they didn’t know what to call it. And it was basically video, performance, and installation. This was another kind of sensibility in the art world – the idea that there wasn’t a ‘high art’ and a ‘low art,’ and that you could make video, and then it could be interesting for all sorts of reasons, but not necessarily because it’s beautiful. They would do all sorts of weird things with installation and light and smoke and mirrors that broke with the earlier ideas about what art-making is, what performance is, and what sculpture is. Those ideas came onstage, for sure, during the punk years.”

From the beginning, there were those who saw punk as an heir to earlier art movements such as Surrealism and Dada. “[N]othing better validates the surrealist perspective on life than the emergence of new wave, in which outrage and art combine to provide means for revolt to claim new terrain,” proclaimed Nico Ordway in a 1978 essay for Search & Destroy, which was particularly keen on emphasising these connections. In addition to Vale and Ordway (né Stephen Schwartz), the zine’s staffers included Ricky Trance (Richard Waara), a “militant surrealist” in the words of photographer Richard Peterson.“In the beginning, he was just as important as Vale,” says Peterson.“He was trying to push a lot of surrealism into the punk scene and Search & Destroy.” Then there was Bruce Conner, the multi-faceted artist who had been operating out of North Beach since the Beatnik era. Already in his forties at the time, Conner nonetheless leaped headfirst into punk and came onboard as a sort of celebrity guest photographer for the zine.

Most of the Search & Destroy brain trust was a good decade older than the members of bands like the Sleepers and Negative Trend. As such, they qualified as elder statesmen relative to these younger musicians. “Vale acted kind of like this uncle,” says Michael Belfer. “He would explain things to us. ‘Andre Breton wrote The Surrealist Manifesto. You should look into it.’ ‘I didn’t know there was a surrealist manifesto, but I do like surrealism. Okay, thank you, Vale.’ So he would steer us towards different things to read.”

Then again, not everyone embraced this guidance, and some actively rejected it. “All the shit that’s written, like some connection between surrealism and punk, makes me sick,” protested Craig Gray in a Search & Destroy interview. “There is no such thing as surrealism in punk. If it is surreal, then it can’t be punk because what we do is the most alive and real thing to us. It’s not a ‘theatre of illusion,’ as Dirk is so fond of saying. It’s our life. Broken, smashed, destroyed.”

Joe Rees: The first time I ever saw Negative Trend, they were playing at a place called the Longbranch in Berkeley, and there were probably about twenty people in the bar. Rozz was wearing a pair of torn Levi’s, and painted on his Levi’s – along the leg – it said, “I HATE ART.” And when I saw that, I just about fell down! Because what the hell does art have to do with it? First of all, you had to know something about art to hate it.

Rozz Rezabek: What I like about it is, it gives people something to think about. You can’t not think about it. “Wait a minute? You hate art?” We might as well have been saying we hate music, but we showed that with our actions – by the way we played.

Will Shatter: When I think of art, I think of sterile environments like museums and galleries. All that stuff’s for rich people. It’s removed from day-to-day life. The artist is creative by proxy for all the people who do shit jobs all their lives, people that scrape just to survive. They rely on the artist to be creative and intelligent for them.

The Trend’s anti-art stance didn’t bother Bruce Conner, whose photograph of Rozz wearing the “I HATE ART” pants has since made its way into the New York MOMA, among other highbrow collections. For that matter, Shatter was also a visual artist of sorts. “He did a brilliant collage that’s in the StreetArt book,” says Peter Belsito, the book’s editor, referring to a piece entitled ‘Today a Piece of Me Died.’

In hindsight, the attitude wasn’t so much anti-art as it was anti-authority. “At the time, we were kids,” emphasises Gray. “All we cared about was what was immediate and what was now and happening at the moment. In a way, it was Zen, but, you know, Zen on speed. It was like, ‘Who gives a shit about surrealism? We’re dealing with right now, and right now is all very real to us.’ I mean, all these guys were trying to teach us stuff. Like Nico Ordway. And then Will got in with those freakin’ stupid-ass revolutionary dudes, Upshot. It’s just like, ‘Fuck off, man. Let us be idiots on our own. If we’re gonna make mistakes, let us make ’em, and then we learn the lessons. We don’t need new parents.’

“We’re talking about ‘Art’ with a capital ‘A,’” he clarifies. “Art with a small ‘a’ is everyday stuff – you know, what people do every day. But art with a capital ‘A’ was exactly what we were trying not to do. The whole idea of fine art or art as an elitist thing – you know, fuck that shit.”

Who Cares Anyway: Post-Punk San Francisco and the End of the Analog Age by Will York is published by Headpress