If the recent student protests have proved anything it’s that people in their teens and twenties, long derided for their indifference, are far from apathetic. And yet, as they take to the streets in their thousands, where is their soundtrack?

For earlier generations social, cultural and economic upheaval was accompanied by artists who sought to reflect and channel the changing mood. But in recent years the relationship between music and protest seems to be in trouble, like a couple who have been married for decades but no longer have anything to talk about.

To find out why this has happened, we have to travel back 20 years to the last time that the two partners still vaguely fancied each other.

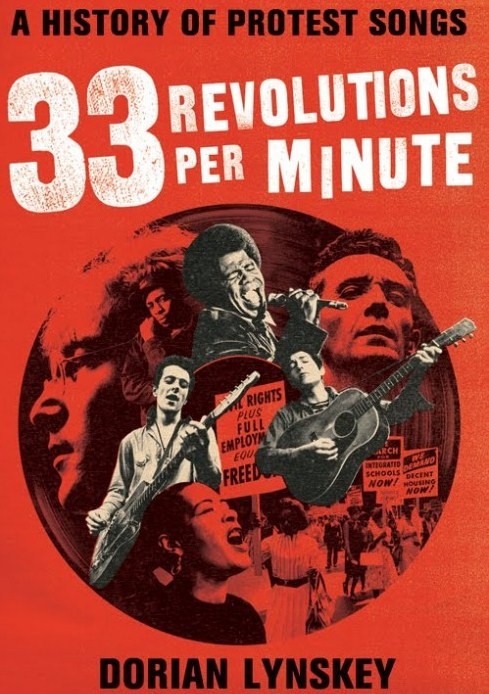

"As recently as the early 90s there was still a strong connection between music and protest," says Dorian Lynskey, author of 33 Revolutions per Minute: A History of Protest Songs. "Although there have always been protest singers and protest songs, specifically on the folk scene, in Britain it was from punk onwards that music became more overtly political. From 1977 until probably Riot Grrrl in 1991/2, you had around a 15 year period when the relationship between music and politics was a particularly strong one."

The wider changes that had been taking place in the country were largely responsible for this; protest music has always emerged out of cultural, political or economic tension. Think of the folk revival in the US during the 60s and the backdrop of civil rights, the rise of the counter-culture and the protests against Vietnam. The same is true of other scenes with a political bent, each one needing a wider tension in society to feed upon.

"From the 70s up until the early 90s, Britain had all the ingredients to produce protest music to a greater level than was previously the case," continues Lynskey. "Massive social change, economic turmoil, a hugely polarised political environment; these are the factors that ensured that what began with punk continued long after that scene had fizzled out."

And this was assisted by the arrival of the independent music scene. Made up of bands drawn from working-class communities and anti-establishment by its very existence, the scene took the attitude and ethic of punk and carried it through to the years that followed.

"Punk had been political and that influenced a generation of bands," says John Robb of The Membranes. "Indie became a musical and political subculture. Everyone was aware – some in good ways some in bad – that music should be political. Whether you did this through your songs or by playing benefits didn’t matter. The important thing was to just do something."

It might sound surprising today, in an age when a mixture of indifference and PR-savvy ensures that few artists from any genre ever veer into the politically contentious, but there was a time when the music press actually expected bands to have opinions.

"Music was the lingua-franca of resistance" says Billy Bragg. "Editors at publications like the NME and Sounds, and other magazines, thought that bands that were featured should have a radical edge, be aware of the political environment and have an opinion about it."

But from the early 90s onwards things began to change. All those factors that had coalesced to make the perfect environment for protest slowly started to disappear. No more Thatcher, then no more Tories. Totemic strikes, which had politicised and galvanised a generation became a thing of the past. And the economy calmed down too. The heady highs and abyssal lows that had blighted the country for years suddenly disappeared. Everything settled down to a gentle rhythm and as a country we became at best contented, at worst simply apathetic.

"All this made politics bland," says Bragg. "The country turned into a different place. It didn’t help that after the collapse of the Soviet Union people stopped talking about left and right and began to cling to the middle. I was no fan of Thatcher but at least you knew where she stood. I still have no idea what Tony Blair stood for. In the whole of society a culture of complacency set in. It’s difficult for protest singers to make music in a vacuum and for most of the past twenty years that’s what this country has been like. You had a generation of people who’d rather go shopping than engage politically. It’s unsurprising that protest music fell out of fashion."

But with a new age of austerity bearing down upon us it looks like things might be beginning to change. Tension in society is starting to make a timely return. The question is, will protest music return with it?

"I had a moment of clarity a few years ago, when the credit crunch first hit. I’d been living in a bubble until then and suddenly it just hit me that people in this country, and others, are getting fucked over left, right and centre. After that I had to do something about it".

The Agitator

Derek Meins, creative force behind The Agitator, is that rarest of things, a protest singer under the age of 25. With song titles such as ‘Let’s Get Marching’, ‘Get Ready’ and ‘No!’ and lyrics that share the same sense of anger evident during the student protests, his band are providing the beginnings of a musical soundtrack sorely needed during these politically combustible times.

"A radical message and a radical sound, that’s what we’re about," he says. "No guitars, just drums and message of resistance. The kind of music you would march to anywhere. Citizens are getting screwed but they can do something about it. You’re seeing the beginnings of change on the streets. It’s about saying no to both the way that things have been done and the way that the country is going now."

Encouraging stuff. During the 70s and 80s it was on the margins of the music industry and in pioneering scenes where most protest music tended to emanate from. In the US that meant hip-hop, in the UK scenes such as punk, post-punk and C86. And in this instance, with their uncompromising, aggressive and inventive sound, The Agitator adhere to that tradition.

According to Lynskey, it’s from these innovative and vibrant musical genres that we should look to for the protest music of the future.

"I think if protest music starts to make a significant comeback, it’s more likely to come from places like Urban or similar scenes. It’s not impossible that something will emerge from more established genres like indie, but really that’s no longer the beast that it was 20 or 30 years ago. The whole thing has become much more corporate, endemically middle-class and culturally introverted. Are we really likely to see Mumford & Sons releasing an album of biting social commentary? Look elsewhere; that would be my suggestion."

Even if as a country we do become more political and develop a desire for this to be reflected musically, according to the folk singer Robb Johnson, often regarded as one of the country’s genuinely political songwriters, one development of the last twenty years that seems unlikely to change is the attitude of the popular media.

"Years ago, there were opportunities for politically minded songwriters to occasionally reach a mass audience. For all its faults, even a show as populist as Top of the Pops still featured interesting artists now and then. What’s left today? We’ve reached the point now where you’ve got things like Jools Holland – effectively just a cosy televised version of Mojo magazine – and the X-Factor, a show that is very unlikely to have a protest song week. Political or protest singers are going to have to work harder to get their music out-there."

What seems apparent is that the coming years are going to be different to the two decades that preceded them. As a country we’re slowly emerging from our debt induced stupor and stumbling bleary-eyed around a very different landscape.

"The possibility is now becoming clear to a lot of people, specifically the young that living standards could fall in the future. In fact, this could be the first generation of young people who have lower living standards than their parents," says Billy Bragg. "It’s going to make a lot of people want to challenge the system. That’s what got me radicalised; the realisation that the things that I valued in life were under attack. In an age of fractured media, music might not be as important as it once was but it still has a role to play and now that resistance is back, don’t be surprised if the music of resistance isn’t far behind."

Jim Keoghan

Given how good this voluminous book on popular recorded protest song is, it feels almost churlish to draw attention to the fact that John Lennon’s sharp-featured profile takes up more space on the cover than Billie Holiday, Chuck D and James Brown in combination. But once you’re past considerations of graphic design and marketing, this is an intensely satisfying read.

Lynskey, a Guardian music journalist, has put in the hours at his local library doing the kind of job which is all too rare in this age of cut-and-paste atrocities. (Leaving aside the fact that no one needs a book on MGMT — how good can one be anyway, if it’s rushed out less than four months after an album?) The fact that the appendices, sources and epilogue run to 120 pages should speak volumes alone.

Any trepidation you have before diving in is forgotten almost immediately. (200 pages on folk music? Sweet baby Jesus save me!) This reader probably enjoyed the sections on the singers and acts he cannot abide more than the rest. The author’s trick is to convincingly win back important musical figures — some of them genuine revolutionaries —from jabbering talking-head, TV filler shows and their songs from the defanged and whimsical soundtracks in which they have been used as signifiers for years. His knowledgeable, hard-boiled prose is slashed through occasionally with fine razor cuts of vivid description which jolt you out of any reverie you may have slipped into: it’s a good read but it’s not an easy read.

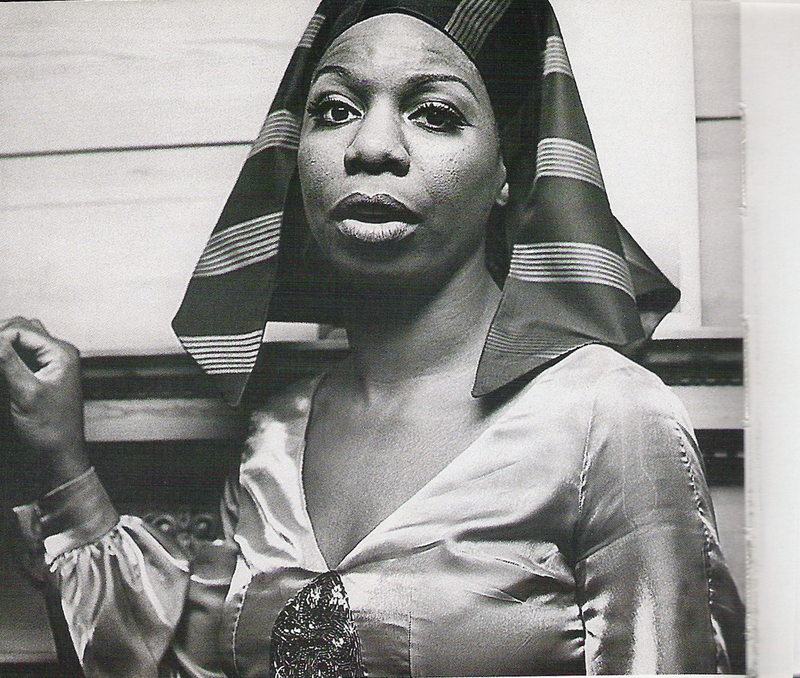

The chapter on Nina Simone reveals how she was unable to keep on ignoring the burgeoning civil rights movement, after the KKK bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama that killed and injured 14 black kids. The author describes it: "As the bomb detonated and rafters buckled the teacher shrieked: ‘Lie on the floor! Lie on the floor!’ [One of the children who died] Cynthia’s father Claude would recall, ‘Even as she screamed, the faces of Jesus in the church’s prized stained-glass window shattered into fragments.’"

And then we are left with Simone, who is almost tipped over the edge by the event, angrily trying to build a zip gun from household items so she can go into the street and kill a stranger. Instead we got the shocking ‘Mississippi Goddam’. And shocking it becomes again when rescued by the context.

John Doran

The launch for 33 Revolutions Per Minute: A History Of Protest Songs will take place tonight at Waterstones, 82 Gower Street. A talk and Q & A session will take place at 6 30pm, with tickets costing £3 (and redeemable if you purchase the book that evening!). For more information and to get hold of tickets, call 020 7636 1577 or email events@gowerst.waterstones.com.